Ana Muñoz van den Eynde

Head of the Science, Technology and Society Research Unit at CIEMAT

The relationship between science and policy is a close one. It has two sides, science policy, which regulates the framework within which science is funded and produced, and science for policy (science advice), which provides scientific knowledge to support political decision-making. For a long time, the two facets of the relationship have worked in parallel and have functioned relatively outside of political confrontation.

Social media and the new way of doing politics, however, have radically changed this situation, although the origins of political interference in science go back further. Because it is more difficult to discern between true and false content on the internet, it is now easier than ever to spread politically motivated fake news. In the United States, social media has greatly accelerated a long-standing political rift in scientific trust. Since Ronald Reagan, Republican leaders have turned science into a partisan arena. The ideology of deregulation and limited government action is one of the main reasons for this attitude. Republican lawmakers often ignore environmental issues despite the scientific consensus on their causes and effects.

President Trump has taken suspicion of science to another level by treating it as just another political opinion. In his view, scientists and institutions that contradict his views are motivated by their political agendas and this has led him to claim that the science they offer is false. The fact that the acceptance or rejection of science is increasingly determined by political affiliations threatens the autonomy of scientists. Once a theory is labelled ‘conservative’ or ‘liberal’, it becomes difficult for scientists to question it. Thus, some scientists are less likely to question hypotheses for fear of political and social pressures.

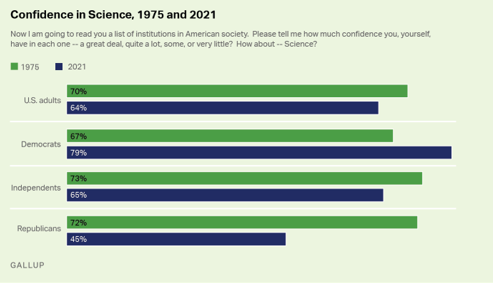

In any case, a Gallup poll conducted in 2021 showed a small decline in the percentage of US adults who said they had a great deal or a fair amount of confidence in science compared to a 1975 study. The percentage dropped from 70% to 64%. However, that small change masks much larger changes, reflecting a complete divide in support for science between Democrats and Republicans.

On the other hand, people are increasingly viewing scientific issues through a political lens. In the past, that politicised conversation focused mostly on climate change, energy and other environmental issues. But since the pandemic, and as a result of this new way of doing politics, we are seeing it move into other areas. The problem is that in a society as polarised as America's, it's not just about trust in science, it's also about people's perception of how much they trust science versus how much the other side trusts science. The more hostility one feels towards the other side, the less willing one is to accept it.

A paper just published in Nature shows that political polarisation also influences the use of science in policy-making. An analysis of hundreds of thousands of policy documents reveals striking differences in the use of scientific literature by policymakers from each party: Democratic-led congressional committees and left-wing think tanks are more likely to cite research articles than their right-wing counterparts.

Most seriously, when science is ideologised in this way, the discussion shifts from facts to ideology. This is what this article reflects, and this is what is particularly worrying. In particular, it indicates that Republicans are very willing to follow health recommendations now that they have their own people in government. And we already know what profile the person in charge of health policy in the US has at the moment.