New clues to ovarian ageing discovered

The decline in egg quality has been considered the main cause of declining fertility with age. A new study published in Science shows that the cells and tissues surrounding the oocytes within the human ovary also play a crucial role. They identified 11 types of cells in the ovaries, including nervous system cells, that influence follicle development. In addition, they have discovered that oocytes are grouped into “pockets” within the ovary and that the density within these pockets declines over the years.

251009 ovario rocío EN

Rocío Núñez Calonge

Scientific Director of the UR International Group and Coordinator of the Ethics Group of the Spanish Fertility Society

Eggs are formed in the ovary through a process called oogenesis, which begins before birth and is completed during puberty. During gestation, germ cells (or oogonia) transform into primary oocytes, which remain in a phase of cell division (meiosis) until puberty. From then on, each menstrual cycle allows one of these oocytes to resume its development: it completes the first part of meiosis and becomes a secondary oocyte, which in turn remains in a state of descent until fertilization, when it finally transforms into a mature egg.

Female fertility begins to decline from the age of 25 and more markedly after 40, when the chances of conceiving decrease dramatically. The number of primordial oocytes (non-renewable reserves) determines a woman's reproductive capacity, although accurately measuring their number remains difficult. In clinical practice, antral follicle count using ultrasound and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) levels are used as indicators of ovarian reserve, although their exact relationship with the actual number of primordial oocytes is still not fully understood.

For a long time, it was thought that declining egg quality was the main cause of reproductive aging. However, this recent study led by Diana Laird showed that the cells and tissues surrounding the ovary also play a crucial role in egg maturation and the rate at which fertility declines.

The team analyzed how the ovary functions and ages in mammals, comparing in detail what happens in mice and humans. Their goal was to understand which aspects of the process are shared across species and which are unique.

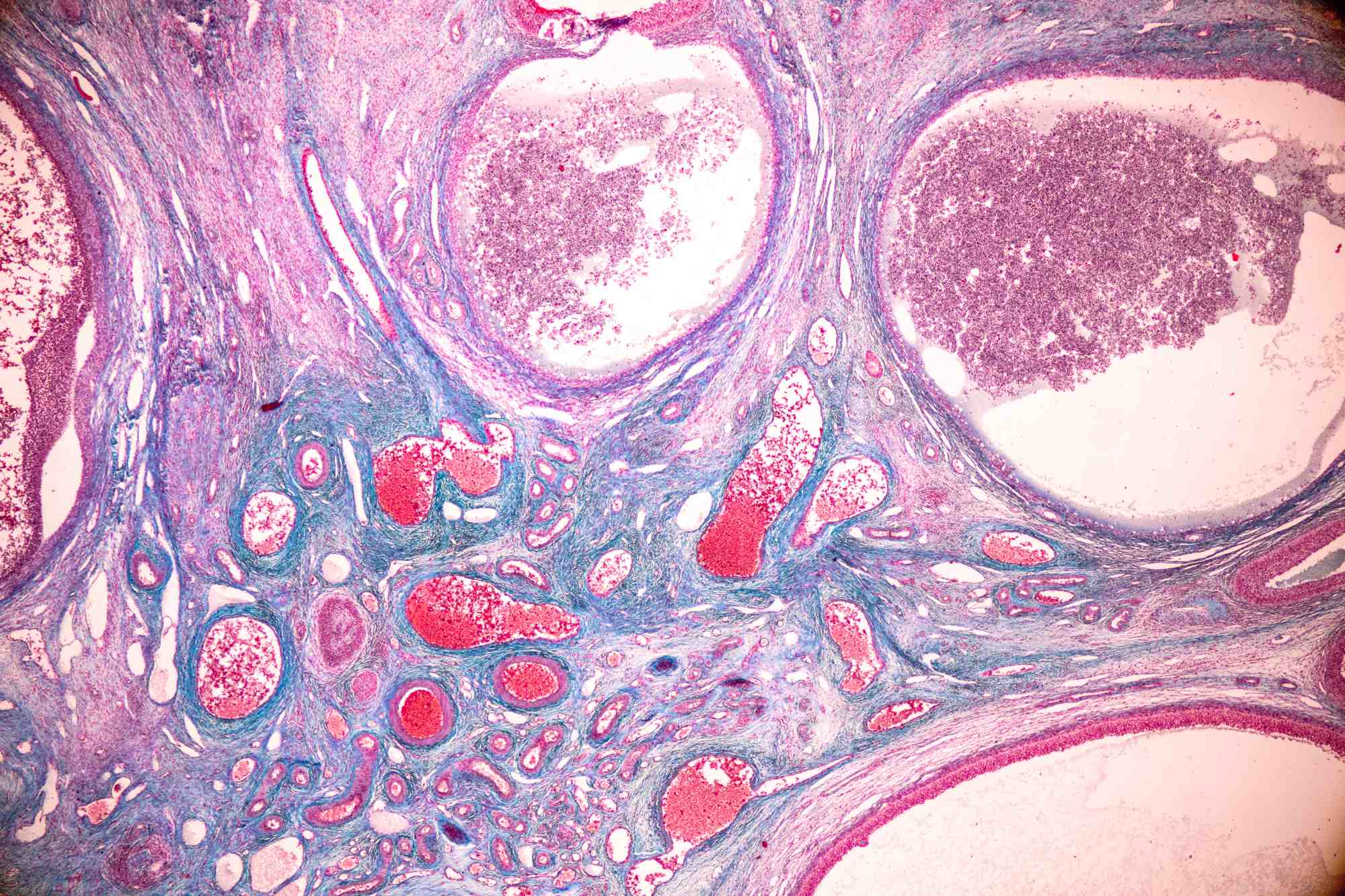

To achieve this, the researchers studied ovarian cells one by one, using technologies that allow them to determine which genes are active in each cell. Furthermore, they developed an innovative three-dimensional imaging technique that allowed them to observe the eggs within the ovary without having to cut the tissue into layers, as was previously done.

In mice aged equivalent to 30 to 40 years in humans, they observed a drastic decrease in both immature eggs in reserve and those that had already begun to mature. Similar to what occurs in women of that age, these mice also had a low success rate in in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments.

When applying this technique to human ovaries, the scientists discovered something surprising: the eggs are not evenly distributed, but rather clustered in "pouches" separated by egg-free areas. Over time, the number of eggs within these pouches decreases.

The team also identified a little-known cell type, present in both mice and humans, and discovered that sympathetic nerves (the same ones involved in the "fight or flight" response) form a dense network within the ovary that intensifies with age. When these nerves were removed in mice, the number of eggs in reserve increased, but the number that matured decreased, suggesting that nerves may influence when eggs begin to develop.

Furthermore, they observed that other support cells, called fibroblasts, also change with age, causing inflammation and scarring in the ovaries of women in their 50s, long before similar processes appear in other organs such as the liver or lungs.

By combining different technologies, Laird's team created a "cellular atlas" of the ovary, a map showing the different cell types and how they change over time. Understanding these changes could be key not only to prolonging fertility, but also to improving overall health. Many aging-related diseases increase in risk after menopause or after ovarian removal, and slowing down the aging process could help reduce these risks.

Currently, Laird's group is initiating new studies to investigate whether certain drugs could modify the rate of ovarian aging. Their goal is to find ways to delay reproductive aging, with potential benefits for both fertility and common diseases in postmenopausal women, such as cardiovascular disease.

The study has some limitations, mainly the difficulty of obtaining ovarian tissue from women of childbearing age who are not undergoing medical or fertility treatment. Therefore, most of the human samples came from postmenopausal women, supplemented with cells from younger donors. In the case of mice, a common research strain was used, facilitating comparisons with other scientific work.

In the future, the researchers plan to include more samples and species to refine this model. Taken together, their findings improve our understanding of the mouse as a model for studying human ovarian biology and provide a valuable foundation for future research on fertility and aging.

Eliza A. Gaylord et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- People

- Animals