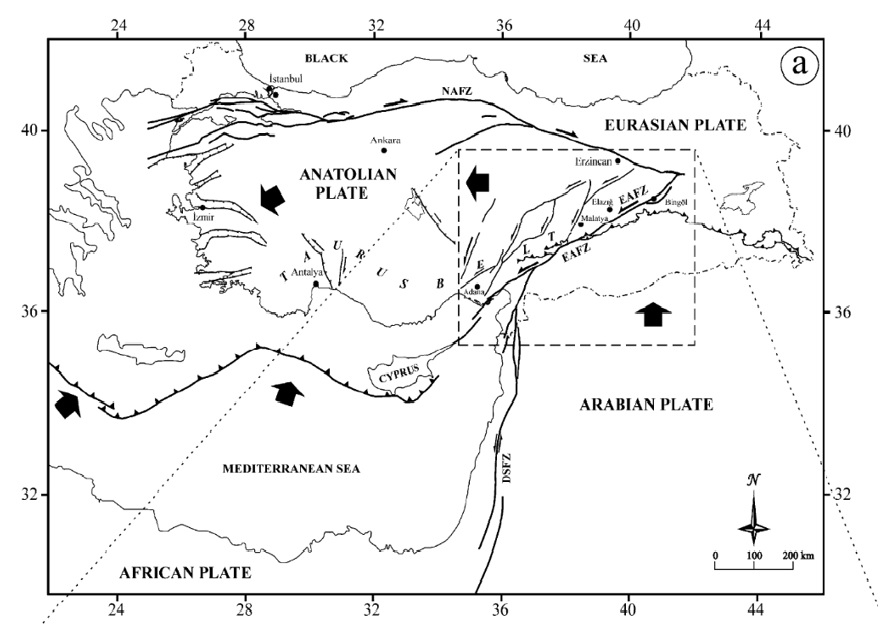

The 6 February 2023 earthquake in Turkey occurred along the active East Anatolian fault (figure 1). An active fault is a plane of weakness in the earth's crust, a fracture that can extend from the surface to a depth of 12 kilometres or more. Faults vary in length, which in the case of the East Anatolian fault is just over 400 kilometres. These faults are under pressure due to the movement of tectonic plates. Under this stress, pieces of these faults rupture and the blocks of land on either side of the fault move. The friction between the blocks produced by this movement releases energy in the form of earthquakes.

Faults can rupture often (every few decades to hundreds of years, such as the East Anatolian and, its compatriot, the North Anatolian fault) or very rarely (every 10,000 years or more, such as the Alhama de Murcia fault in southeastern Spain). The most devastating earthquakes, with magnitudes greater than 6.5, can be generated on faults.

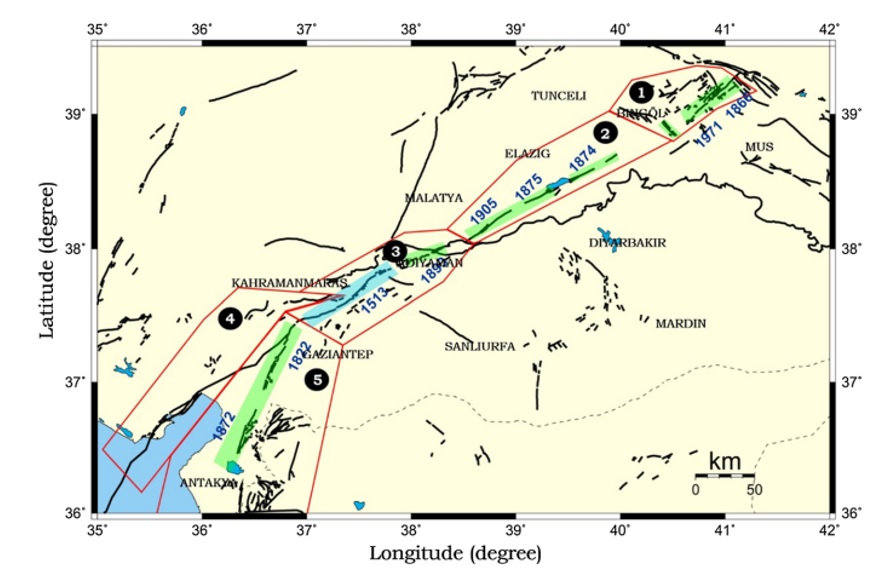

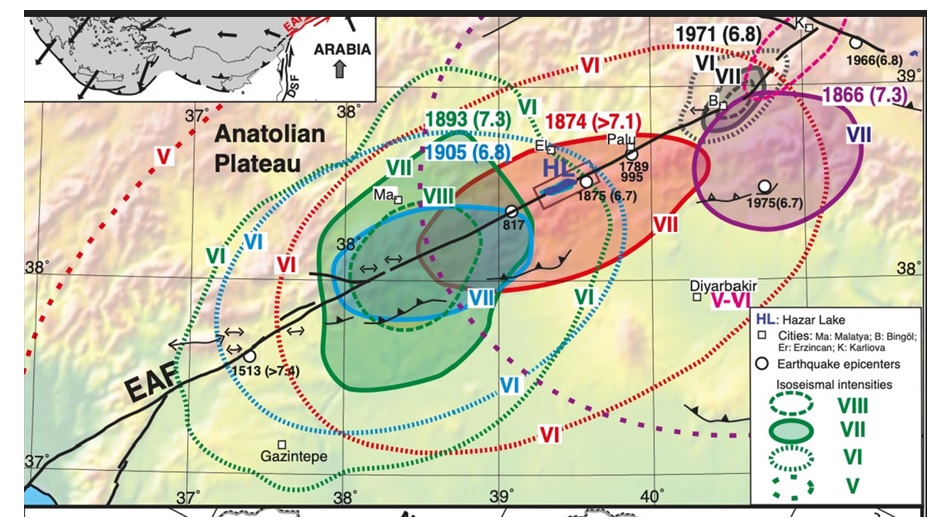

Numerous historical earthquakes have been generated along the Anatolian fault, producing ground rupture and strong shaking in the surrounding area (Figures 2 and 3). The series from the latter half of the 19th and early 20th century is the most well documented. During these decades, practically the entire fault ruptures in successive events except for the section that ruptured in the earthquake of 6 February 2023, which last ruptured in 1513.

The importance of palaeoseismological studies

Palaeoseismological studies focus on earthquakes occurring before the historical period. These studies are very important because they give us an idea of the pattern and frequency of fault rupture and, therefore, of large earthquakes. This information is used to generate seismic hazard maps that can be used to design buildings and infrastructure appropriately to withstand strong shaking during an earthquake. There are some studies on the East Anatolian fault but most studies of this type in Turkey have focused on the North Anatolian fault, which is very close to Istanbul.

For most of the faults in the world there is no such clear historical data as for the faults in Turkey. This is because many faults rupture at time intervals longer than the historical period. Paleoseismological studies are therefore necessary, especially on "slow" faults. In Spain several institutions and universities are developing paleoseismological studies to better understand the frequency of these large earthquakes in the Iberian Peninsula.

Economic difficulties cause some regions to rebuild their buildings after an earthquake using the same techniques and materials as those that have collapsed

Earthquake-resistant design of buildings and infrastructure is not only a question of scientific knowledge of earthquake frequency. It is often a cultural and financial issue. Each region has different materials with which its buildings are traditionally constructed. Traditional brick, adobe and stone buildings tend to be more vulnerable to strong earthquake shaking. Traditional wooden buildings are more flexible and can withstand shaking better and, of course, modern reinforced concrete buildings with earthquake-resistant designs are the most appropriate, but often unaffordable for certain regions. Economic difficulties cause some regions to reconstruct their buildings after an earthquake using the same techniques and materials as those that have collapsed.