Where do "these children" come from?

They are natural climatic cycles that have been occurring for millions of years. "El Niño is an anomalous warming of the waters of the Equatorial Pacific which, in their eastward movement, meet the Central American isthmus and bifurcate. The most important branch goes southward along the coasts of Ecuador, Peru and Chile," Javier Martín-Vide, professor of Physical Geography at the University of Barcelona, explains to SMC Spain.

Although it is an oceanic process, it also has an impact on the atmosphere. "The atmosphere very often behaves as is the surface temperature of sea waters, and warm sea waters destabilize it because they heat the air above them, which rises and can condense its vapor and produce clouds and precipitation," the scientist continues.

Does this affect the whole planet?

"A hundred years ago it was thought that this was a regional phenomenon, but today we know that when there is an El Niño phenomenon, or its opposite La Niña -with colder than normal waters-, it sometimes results in torrential rains or very severe droughts in very distant places," says Martín-Vide.

"It has many effects and is a relatively complex and more unpredictable system than you might think," Dario Redolat, climate change and meteorology consultant at the Foundation for Climate Research, tells SMC España. "Especially as we move away from the Pacific basin." El Niño is an excess of heat that, although it may seem slight because it is between 1 and 2 ºC, represents a large energy reserve because the ocean is very extensive and this heat is poured into the atmosphere.

"The most obvious effects are seen in the Pacific basin, especially in South America," explains Redolat. "On the coasts of Peru, Ecuador and Central America there tends to be more cloudiness and rainfall, and in winter it can generate more evident effects in North America and weaken the monsoon in East Asia, where there are more forceful and longer dry periods."

It is, therefore, a phenomenon that affects virtually the entire world although sometimes with a time lag of weeks or even months. "It is the greatest teleconnection on the planet because it connects very distant regions and is the main mode of connection between the atmosphere, ocean and distant continents," explains Martín-Vide.

But the effects of El Niño go beyond the purely meteorological. A study published a few days ago in the journal Science calculated the extent to which this phenomenon affected global economic growth. The researchers estimated the losses associated with the 1982-83 event at more than 4 trillion dollars, and warned that these could reach 84 trillion dollars over the course of the 21st century in a context of climate change.

Does it also affect Spain?

Europe and Spain are far from the American coasts. Although the El Niño phenomenon affects the whole world, its impact on our country is not among the greatest. "The El Niño signal in the Mediterranean basin is weak," explains Martín-Vide, "We are not the region of the planet that feels its effects most directly because the Mediterranean is a very unique sea, almost closed and surrounded by relief," he adds.

This does not mean that El Niño has had no impact on Spain in the past, nor that it will not have one this time. "Everything points, but with great uncertainty, to the fact that next autumn and summer we could experience greater rainfall irregularity with the possibility of torrential rainfall," adds Martín-Vide. The researcher recalls that the El Niño of 1982-83 was very large and that in Spain it coincided with "some of the most notable episodes of torrential rains", such as the so-called Pantanada de Tous (1982).

Redolat is cautious in his forecasts and explains that it is important to speak in terms of probability, but without guaranteeing anything. "It is true that with El Niño low pressure anomalies have been observed during summer and autumn, but these correlations and patterns do not ensure that a year with this phenomenon will mean a wetter autumn or more abundant rainfall at the end of summer. It is possible, but we must be cautious and avoid sensationalist headlines".

If El Niño is a warming phenomenon, does it mean that this summer will be hotter in Spain?

No. "You cannot draw a cause-effect relationship with such a distant phenomenon when in Europe we have other variables such as the North Atlantic oscillation," warns Redolat. "In summer there are no significant linear correlations between atmospheric temperature in Spain and sea surface temperature in the Pacific."

However, there may be more complex "nonlinear relationships" to study: "These interactions tend to be visible during certain months or weeks, so they are masked if we look at a set of annual data".

But when will El Niño arrive?

As the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) indicates, El Niño occurs on average every two to seven years and episodes usually last between nine and twelve months.

On 4 July, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) declared the onset of El Niño conditions. "The declaration of El Niño by the WMO is the signal for governments around the world to mobilise preparations to limit the impacts on our health, our ecosystems and our economies," said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas.

According to the WMO statement, El Niño conditions have developed in the tropical Pacific for the first time in seven years, setting the stage for a likely rise in global temperatures and altered weather and climate patterns.

If La Niña has lasted three years, does that mean we are in for a long El Niño?

This is an unanswered question. Redolat explains that the models used to predict El Niño and its phases are dynamic: "We cannot know for sure if it is going to be a longer El Niño coming from a longer La Niña".

The WMO latest update forecasts that there is a 90 % chance that the El Niño will continue into the second half of 2023. It is expected to be at least moderate in intensity.

How does climate change affect El Niño?

Martín-Vide clarifies that El Niño "is not a consequence of climate change", since it has been occurring for about three million years, after the union of North and South America. The experts consulted are also cautious about the implications that current global warming may have on this phenomenon.

"Global warming will most likely change some of the characteristics of El Niño in terms of frequency or intensity," says Martín-Vide, "A few years ago it was said more emphatically, but now the statement is more cautious."

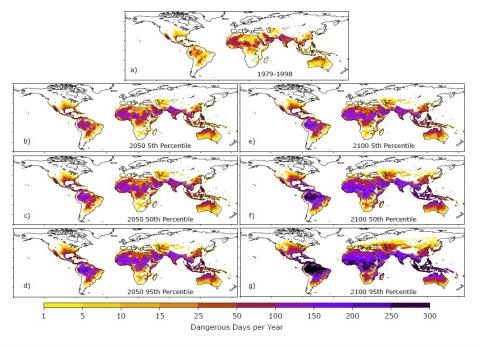

Still, a few days ago the WMO warned that the combination of El Niño and greenhouse gases is likely to cause global temperatures to reach unprecedented levels in the next five years. According to the agency, there is a 66% chance that the 1.5°C warming barrier will be exceeded in at least one of the next 5 years.

"In a context of climate change El Niño tends to intensify and more intense phenomena are expected, although it is not clear how it will affect its length," says Redolat. This is because, in principle, a greater amount of heat means that the atmosphere has more capacity to accumulate water and intensify the monsoons in places like South America and Asia. The expert, however, believes that it remains to be studied to what extent this would imply more intense rains in other places such as Europe.

Why are these phenomena so called?

Every year, when Christmas approaches, the waters of countries like Chile and Peru, which are usually very cold because they come from southern latitudes, warm up a little. Already in the 19th century, Peruvian fishermen baptized these warmer waters as "El Niño", in reference to the birth of Jesus Christ. The name La Niña was given in opposition to the opposite phenomenon.

As we have seen, in addition to El Niño (warm phase) and La Niña (cold phase), there is also a neutral phase, in which the equatorial Pacific neither warms nor cools. The set of the three phases is called ENSO or El Niño-Southern Oscillation.