Reaction to study claiming that seasonal H1N1 flu is a direct descendant of 1918 flu

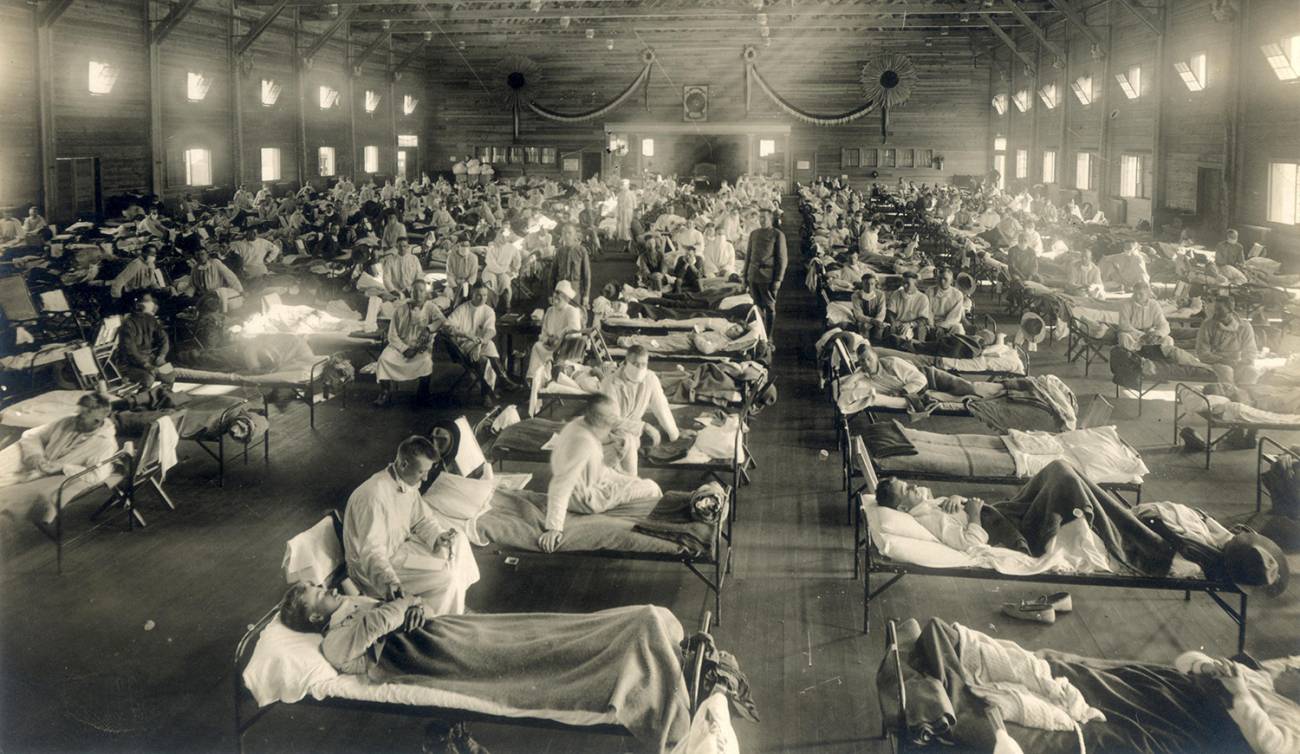

A study published today in the journal Nature Communications analyses the genomic variability of the influenza virus responsible for the 1918 pandemic and how it gave rise to the subsequent seasonal H1N1 influenza.

Adrian - 1918

Adrian Hugo Aginagalde

Spokesperson of the Spanish Society of Preventive Medicine, Public Health and Health Management (SEMPSPGS), Head of Service of the Epidemiological Surveillance and Health Information Unit of Gipuzkoa and, previously, Head of Service of the Population Screening Programmes Unit at the Ministry of Health

This work attempts, through RNA sequencing of samples from people who died at the time and the molecular clock technique, to determine the timing of the mutation and the degree of similarity to the circulating H1N1 influenza.

This is compatible with the hypothesis that has been used historically so far. According to this, there must have been a mutation between autumn and winter 1918 that increased its virulence compared to the virus circulating between spring and summer 1918. It was known that such a mutation must have occurred, although there was no evidence for it, but that the genetic distance must not have been sufficiently high for those who had been infected in the first wave not to retain immunity in the second. At the same time, the data are consistent with what is known about H1N1 influenza viruses, namely that prior to 2009 they were related to the 1918 virus.

It is interesting that they have not only used samples from people buried in the permafrost, as was previously the case, but have also incorporated pieces preserved in the Museums of the History of Medicine. This makes it possible to broaden the geographical scope of the study and to better study the differences between the virus samples circulating on both sides of the Atlantic.

It confirms that acute respiratory virus infections do not disappear, but displace previous serotypes and become seasonalised, causing increases in mortality in the following winters. Also that there is no herd immunity in these viruses to block transmission and that there is no natural (or intrinsic) tendency to reduce their virulence.

It is the disappearance of the extraordinary risk factors that favour transmission and increase vulnerability (such as a World War), as well as the decrease in the number of susceptible people, that causes its impact to diminish; but without disappearing, generating occasional excess mortality higher than expected in subsequent winters and without mutations that increase its benignity.

María - 1918

María Iglesias-Caballero

Virologist at the Reference Laboratory for Influenza and Respiratory Viruses of the National Microbiology Centre - Carlos III Health Institute

The characterisation and study of the influenza virus of the 1918 pandemic is a very interesting field. It allows us, with the current methodology, to learn more about the virus that caused a pandemic that has similarities with the one we are suffering today.

This work vindicates the importance of well-preserved archived collections, which are a source of material that allows us to update, with the development of new methodologies, information on past pathogens that can provide information applicable to the present and future.

The main limitation of the work is the number of samples used, as is normal given the difficulty of obtaining them. Despite this limitation, the methodology used to obtain the new virus sequences by mass sequencing and the evolutionary models used are adequate and allow the results presented to be obtained reliably.

The comparison of European samples prior to and during the peak of the pandemic with American samples provides information on the viral variability that could exist between pandemic viruses and the host adaptations that could have arisen.

This information allows today's virologists to monitor changes in these positions in animal viruses or during the emergence of new pandemic viruses. This work provides a description of changes that affect the activity of the virus polymerase, although we do not know if this has a real impact on virus replication, and changes that may be associated with host adaptation in the nucleoprotein and that would also improve the ability of the virus to respond to the innate immune system.

In 2014, Rambaut et al. published a paper linking the origin of the virus to the recombination of a haemagglutinin from a circulating human H1 virus with 7 segments of an avian influenza virus. This paper, which cannot rule out that hypothesis, presents a new alternative. Phylogenetic analysis, using newly available prepandemic sequences, reveals robust association of all internal genes of seasonal and pandemic viruses, except for haemagglutinin and neuraminidase. In the case of viral antigens, these segments cluster better with swine viruses than with hitherto circulating influenza viruses. The evolutionary divergence between seasonal and pandemic haemagglutinins and neuraminidases calculated with different evolutionary models shows the possibility of a different origin than proposed so far.

- Artículo de investigación

- Revisado por pares