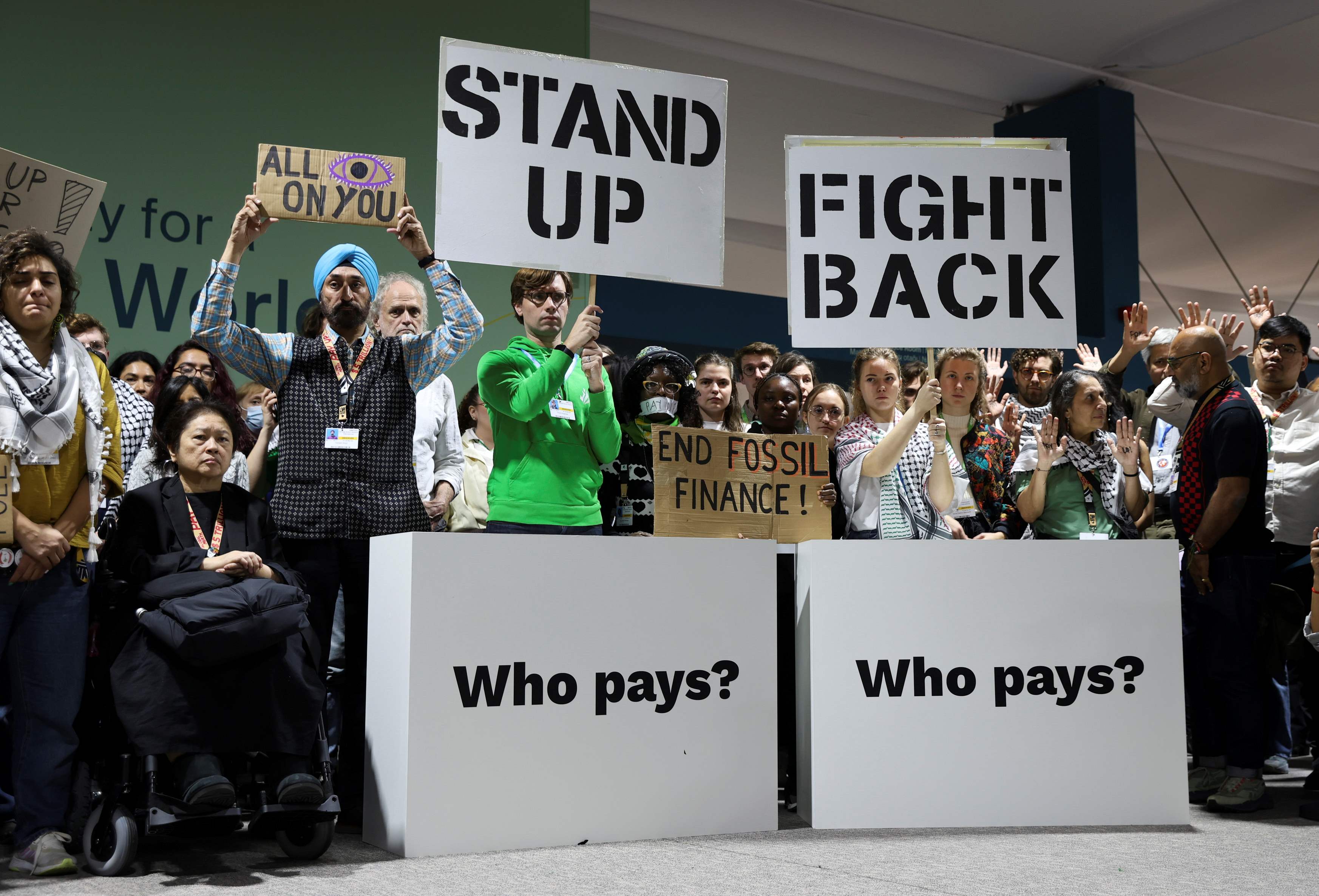

The 29th UN Climate Conference in Baku (COP29) ended this Sunday with an agreement in extremis that has not left either the countries of the global south or social organisations satisfied. Dissatisfaction with the agreement is caused, among other reasons, by the resources allocated to the fight against climate change by rich countries to developing countries (300 billion dollars a year in funding for 2035, far below what was demanded) and by the absence of a clear commitment to abandon fossil fuels.

Time will tell if the agreement is fulfilled and the 1.3 trillion dollars of total funding per year for 2035 is reached, and if it is distributed in such a way that it really serves to reduce global emissions and bring us closer to the goal of a temperature rise below 1.5 ºC with respect to pre-industrial levels.

What COP29 did serve to demonstrate, once again, is that the fight against climate change is global and requires the involvement of everyone, and to remind us of our commitments under the Paris Agreement, such as the European Union's commitment to achieve climate neutrality by 2050.

Universities and research centres are key to this challenge. We need to study climate change and its consequences. We need to develop clean energy. We need technologies for capturing greenhouse gases and for mitigating and counteracting the effects of climate change at all levels: health, biodiversity, food, urban planning, etc. We need to define new models of production and relations of solidarity and cooperation between countries.

Laboratories and research centres are responsible for a high volume of emissions and waste

At the same time, we cannot ignore the fact that research is itself a resource- and emission-intensive activity. In addition to those associated with travel for field research, conferences and meetings, laboratories and research centres are responsible for a high volume of emissions and waste. Here are just a couple of facts from this article: biomedical research laboratories consume between 5 and 100 times more energy than commercial spaces of equivalent size, while each biomedical researcher generates almost one tonne of plastic per year (Urbina, 2015). In addition, research is increasingly intensive in simulations, computing, big data and artificial intelligence, with subsequent environmental costs in terms of energy, water and extraction of natural resources for electronic components (Lannelongue, 2023).

Climate-neutral practices

It is therefore essential that research institutions also develop strategies to incorporate more sustainable practices and contribute to climate neutrality. This involves developing tools to measure their emissions and waste, and defining and adopting new algorithms and processes to minimise them. In addition, the scientific community must be involved in training a new generation of researchers to put sustainability on their agenda. Sustainability needs to be incorporated into the reform of research evaluation, ensuring that collaboration, open science, the elimination of redundant experiments or experiments of limited scientific value, and the minimisation of environmental costs associated with research efforts are valued.

To drive this paradigm shift, researchers need resources and incentives, and this is where research funders play a key role.

On the one hand, research agencies can encourage the introduction of sustainability in their calls for proposals through eligibility requirements or by requesting a self-assessment of the environmental costs of the projects to be funded.

Research agencies can encourage the introduction of sustainability in their calls through eligibility requirements or by requesting a self-assessment of environmental costs

In addition, funders should adapt their calls to promote more sustainable practices by, for example, limiting the number of trips; encouraging the sharing of equipment; accepting as eligible costs the repair and purchase of second-hand equipment, the use of tools to calculate carbon footprints or obtaining sustainability certifications; funding the training of researchers, and the incorporation of staff specialised in sustainable research practices.

To discuss how research funding institutions can promote sustainability in research, we met last May in Heidelberg at the invitation of EMBO (the European Molecular Biology Organisation). The meeting was attended by representatives of funding agencies from the United Kingdom, France, Poland, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Austria, the European Commission, associations working for sustainability in research, and some research centres that have already developed research sustainability strategies, such as the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) and the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC).

As a result of that meeting, the Heidelberg Agreement was recently published, urging funders to work together to implement sustainability strategies and introduce environmental requirements in their calls for proposals, as well as to support the development and adoption of tools to help research staff integrate sustainability. Some funders are already doing this, but many more need to join in and establish a new way of doing research, as has happened in the past with ethics or gender equality.

In my opinion, a model to follow would be the creation at European level of a seal of excellence in sustainability similar to the successful seal of excellence in human resources HR Excellence in Research Award.

The institutions gathered around the Heidelberg Agreement invite funding agencies and the scientific community at large to join in and continue working to ensure that research is conducted as sustainably as possible and that we all contribute to a better world for future generations.