Which species are considered migratory birds?

Migratory birds are those that move seasonally between their breeding and wintering grounds on a regular basis every year. As Javier Pérez-Tris, Professor of Biology at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM), explains to SMC Spain, one of the characteristics of these species is that they live more intensely and die younger than sedentary birds: ‘Migration is dangerous for many reasons.’ These include the loss of stopover sites due to climate change or the passage of species through different countries with different environmental policies, legislation and conservation measures that affect these intermediate stops.

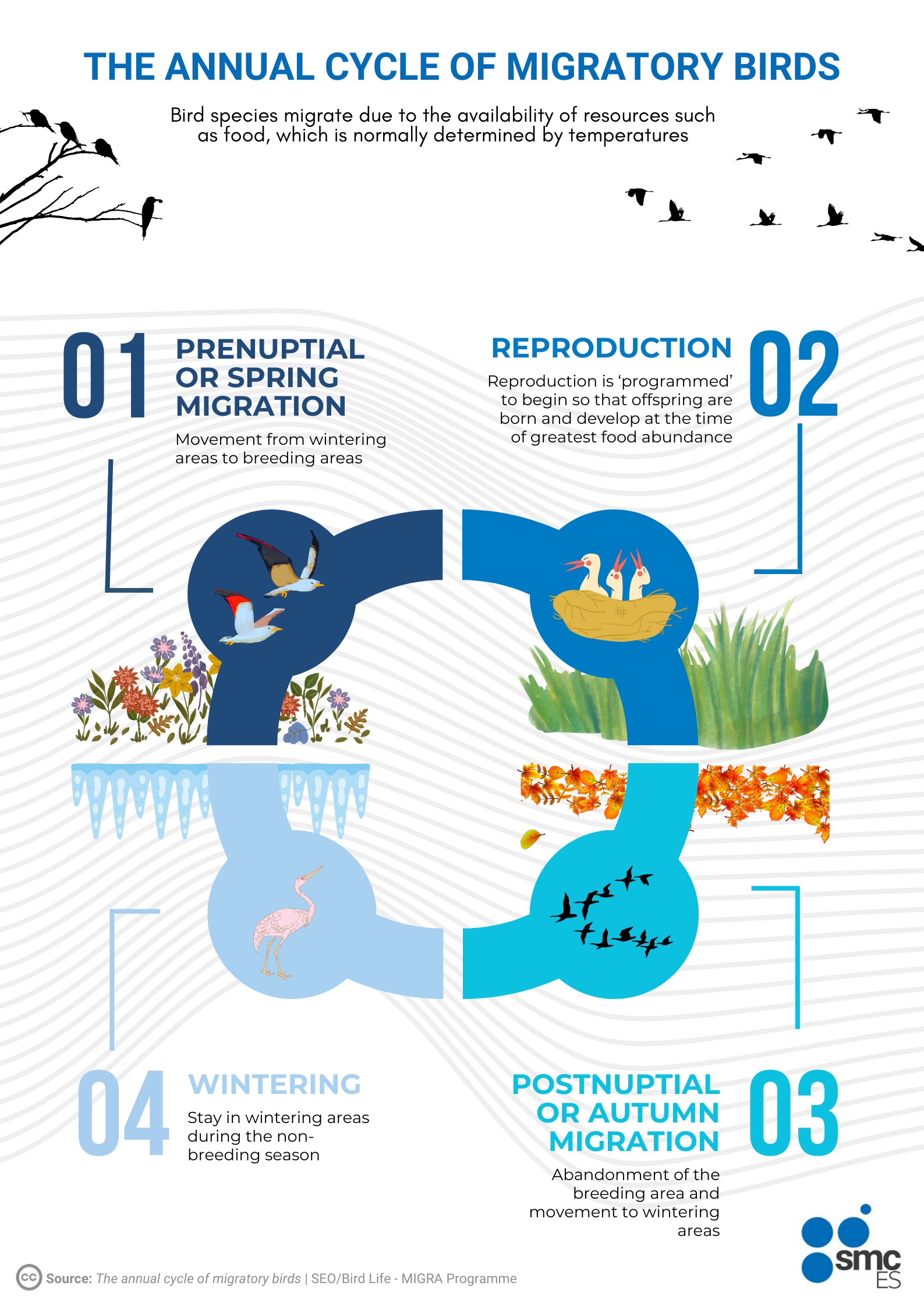

Arantza Leal, ornithologist and technician at the Species and Spaces Unit of SEO/BirdLife, tells SMC Spain that the main reason birds migrate is because of the availability of resources — mainly food — which ‘is normally determined by temperatures.’

A study published in the Journal of Comparative Physiology A highlights the fascinating behaviour of migratory birds, but also warns that they are under particular pressure in a constantly changing world. These species have the perfect morphology and physiology to fly fast and travel long distances on exhausting journeys that push them to the limits of their capabilities. In addition, they adjust their migratory cycles to the specific ecologies of a population, which implies the existence of genetic, epigenetic and experiential processes to achieve this precision.

Carlos Camacho, PhD in Biology and researcher at the Doñana Biological Station (EBD-CSIC), points out that migratory birds lack information about the conditions they will encounter in their destination areas: ‘Unlike us, they cannot anticipate possible changes.’

Globally, according to data from BirdLife, 17% of all bird species are migratory (around 2,000 of the more than 11,000 species). According to Leal, although the percentage may seem small, this factor characterises ‘millions of birds’. ‘Migration is a spectacular phenomenon that has attracted human attention for millennia,’ says the ornithologist. ‘At the beginning of spring, the swallows arrive, the nightingales sing, the orioles, the cuckoos...’. In Spain, the proportion of migratory birds is almost 80%.

Why are migratory birds important?

José Luis Tellería, professor at the UCM and member of the research group on Evolutionary and Conservation Biology, explains to SMC Spain that migratory birds play a key role in the functioning of many ecosystems.

‘They perform ecological functions that are essential for the proper functioning of ecosystems,‘ Camacho tells SMC Spain. Some of these tasks include seed dispersal and the control of pest species and disease-transmitting insects.

‘Migratory birds are extremely important because of their role in transporting energy on a planetary scale,’ says Pérez-Tris. The UCM professor points out that these species ‘represent millions of tonnes of biomass generated in highly productive regions during their breeding seasons, such as circumpolar regions, which are transported to other regions,’ which has a direct impact on the functioning of ecosystems globally.

Pérez-Tris adds that changes in the migratory patterns of species affect the predators that consume them, as well as the prey of the migratory birds themselves. The researcher explains that bird migration is also key for organisms that cannot move, citing plant pollination as an example: ‘Seeds can be efficiently dispersed by the huge numbers of migratory birds that feed on their fruits to obtain energy for their journey, and parasites and other pathogens also move on an intercontinental scale by taking advantage of migratory flows.’

What are the main threats they face?

Although it depends greatly on the species involved, these birds share several threats: ‘Processes related to global change and the widespread modification of an increasingly anthropic environment,’ says Pérez-Tris, adding that these impacts include not only those derived from climate change, such as the drying up of wetlands, but also others such as agricultural intensification and poorly managed hunting.

The UCM professor explains that migratory birds depend on the good conservation status of different places, which sometimes span global contexts. This is a threat in itself, as their conservation ‘requires coordination between different administrations, often from different countries’.

For his part, Camacho highlights the loss and deterioration of breeding, resting and feeding sites for migratory birds as a result of urbanisation, agriculture, deforestation and climate change. The latter factor ‘alters the degree of synchronisation of birds with other species with which they interact’.

One of the phenomena that puts these species at risk is light pollution. A study published in Trends in Ecology & Evolution reports that light pollution can intensify the consequences of environmental pollution during migration and even afterwards. These effects cause changes in the behaviour and physiology of the affected populations, hindering their survival and reproductive success during the breeding season.

How is climate change affecting you?

‘In very general terms, they find it difficult to adjust their life cycle to new conditions that change too quickly,’ summarises Pérez-Tris. The UCM professor explains that it is difficult to generalise when talking about effects, since climate change, despite being a global phenomenon, manifests itself in particular responses ’both in environments and in the organisms that depend on them.’

One of the problems facing migratory birds is adjusting their migration dates to the new temporal distribution of the resources they need. ‘If they arrive at their destinations before or after the peak availability of food, they may encounter serious difficulties in meeting their energy needs,’ says Camacho.

The decline in the quality of the breeding areas to which these species migrate has also had a negative impact on the demographics of some populations.

Furthermore, changes in their reference environments are not the only reasons why migratory birds have had to modify their cyclical migrations. A research study published in 2024 in PNAS reports that many species have changed the timing of their migration in order to adapt to earlier springs.

Leal points out that climate change also has specific effects that affect food availability, with phenomena such as torrential rains, sudden drops in temperature and droughts.

How are you adapting to ongoing global changes?

Their adaptation to global changes has been uneven across species: ‘While some seem to have adapted quickly by changing their migration schedules, others have kept them unchanged,’ Pérez-Tris points out.

A research study published in the journal Ecology concludes that although some migratory bird species are able to delay their departure—to cope with factors such as drought or habitat degradation—and compensate for this time by accelerating their pace along their routes, this alteration has a direct negative impact on their survival.

In addition, there are species that are forced to change their migratory destinations. This is reported in a study of 32 bird species in eastern North America, published in PNAS: the birds analysed had shifted their migration destinations by almost half a degree of latitude to the north.

In our environment, Tellería explains that fewer and fewer birds are travelling to our country from northern Europe. ‘There are species that are no longer migrating to our fields to spend the winter,’ he says.

However, the scientific community has not yet found an explanation for the variable adaptation of different species to global changes, or even for the fact that some of them are not changing their migratory routes. ‘We cannot explain why some species choose conservative routes at the cost of huge detours and others rapidly develop completely new migratory programmes,’ say the authors of the study published in the Journal of Comparative Physiology A mentioned above.

What are the main migratory routes affected by these impacts?

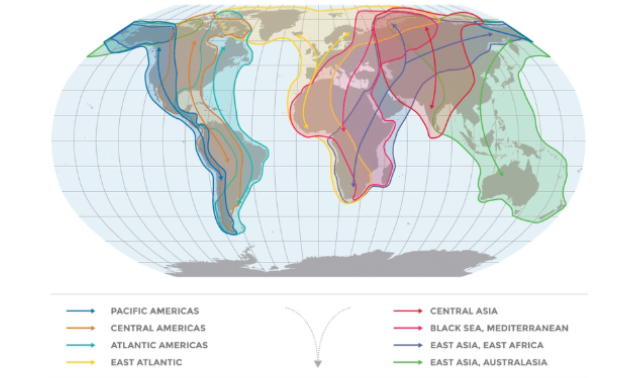

Pérez-Tris emphasises the global nature of this phenomenon: ‘All routes are affected, at least if we consider the main intercontinental migratory corridors.’

Within the migratory corridor in which our country is located—the Western Palearctic Migration System—the Mediterranean basin plays ‘a very important role,’ according to Tellería, in sheltering wintering birds that avoid crossing the Sahara due to its deadly consequences. ‘Considering that the Mediterranean region is a climate change hotspot, it is predicted that vegetation will undergo drastic changes and, with it, the species that depend on it,’ says the professor.

For her part, Leal comments that the different migratory routes of each continent are determined by the climatic characteristics of each region and the availability of food, which is the main reason why birds migrate. ‘These routes are from north to south in autumn and from south to north in spring,’ explains the ornithologist, pointing out that migratory birds tend to spend the winter in regions further south of their breeding grounds because the climatic conditions are milder and food is more abundant.

Within our country, the SEO/Bird Life technique indicates that there are several routes — in the west, east and centre of the peninsula — used by bird species that breed in Spain and which are ‘joined by birds from the rest of Europe as they pass through Spain’. Leal explains that most of these routes converge in the Strait of Gibraltar to cross over to Africa: ‘It is the closest point between the two continents, the shortest distance across the sea’.

At this location, the Migres Programme, which monitors bird migration through the Strait of Gibraltar over the long term, counted 1.12 million birds crossing the Strait between May and November 2024.

How are efforts being made to protect these species?

There are different strategies for conserving migratory birds. Sergi Herrando, a researcher at CREAF and president of the European Bird Census Council, emphasises the importance of the global nature of these measures: ‘Without an international perspective, it is impossible to consider how to protect them or the benefits they bring to our societies.’

Herrando, who is also the scientific director of the Catalan Institute of Ornithology, explains to SMC Spain that the Bonn Convention —the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals signed in 1979— is the ‘most important’ international treaty in this field. This convention, which came into force in 1983, has as its main objective the conservation of migratory species of wild fauna worldwide.

Tellería agrees with the CREAF researcher on the importance of international coordination when implementing conservation mechanisms and points out that this poses an added difficulty as the rules ‘work unevenly’ in different territories.

Both scientists point out that the preservation of wetlands and wetlands, as environments where migratory birds spend time, is a key commitment in the conservation of these species. The most important initiatives for the protection of these environments are the Ramsar Convention and the Natura 2000 Network.

In addition, entities such as the European Commission are promoting ecological restoration projects such as the LIFE AWOM programme. Camacho explains that this plan, in which the Doñana Biological Station is currently participating alongside 12 other entities from six countries, ‘funds an ambitious project that focuses on identifying and restoring important stopover sites for the migration of the black-winged stilt, which is seriously threatened’.

Finally, Pérez-Tris affirms that ‘there is awareness that human development must be compatible with the conservation of migratory birds’ and maintains that work is being done to develop systems that minimise the impact of infrastructure on these species, such as wind farms. The researcher calls for prioritising the planning and development of this type of activity in a manner compatible with the conservation of migratory species and highlights the efforts currently being made to this end, albeit with mixed success.