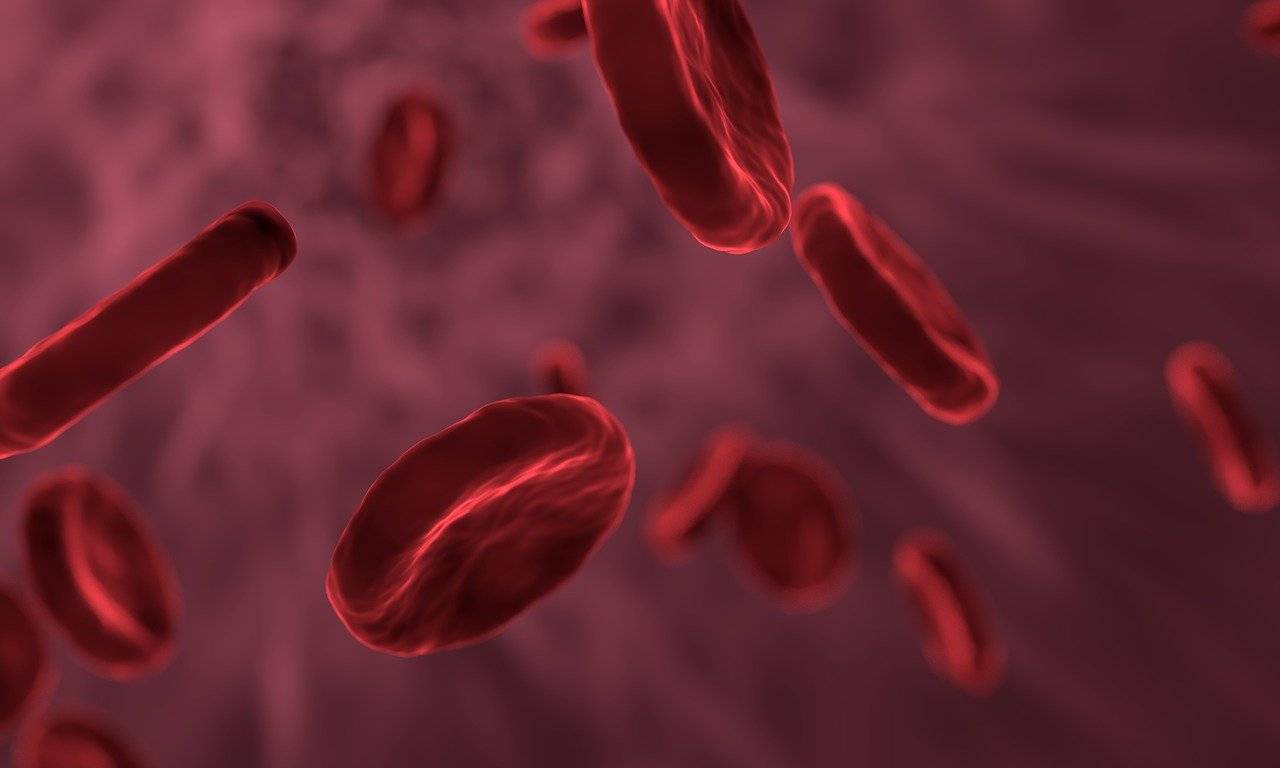

Quite rightly, these days many media outlets around the world are commenting on the findings summarized in the main empirical article published in the latest issue of the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), which most academic physicians consider the most demanding and influential. In the article, Raffaele Marfella, Giuseppe Paolisso, and their co-authors summarize an ambitious prospective study: conducted on 304 people, 257 (84%) of them completed their follow-up for about three years. Although they were asymptomatic, the participants had been well diagnosed with extracranial carotid stenosis [narrowing of the carotid artery] and went to hospitals to undergo a carotid endarterectomy, a surgical excision that can alleviate the accumulation of atherosclerotic plaque (fat, cholesterol, and other substances) in the carotid arteries, in the neck; during the intervention, the surgeon removes the plaque.

The study achieved two types of results of broad scientific and social interest. First, by searching for micro and nanoplastics (MNP) in atherosclerotic plaques, it observed that in the plaques of 58% of the participants, two of the eleven MNP sought, polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride, were detected. Therefore, through complex biochemical, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopy analyses, it detected a considerable and previously unknown degree of MNP contamination in human arteries. And secondly, by following the group or cohort of participants—something common in medicine and epidemiology—it found that those participants whose atherosclerotic plaques contained certain plastics had a risk of dying or experiencing other clinical effects of interest in the following three years 4.5 times higher than those who did not have MNP. That the risk of these effects quadruples or more is relevant; it had never before been analyzed in people under real-life conditions.

That the risk of these effects quadruples or more is relevant; it had never before been analyzed in people under real-life conditions

In the coming years, this plastic contamination and these clinical effects will continue to be defined, refuted, or confirmed in other populations; for example, the mixtures of contaminants under study will be expanded, as well as the characteristics of the individuals and their follow-up time; more factors, effects, routes of contamination, or interventions to prevent it will be considered. We will also better understand the pathophysiological mechanisms that connect exposures to certain plastics—thus, the proinflammatory and immunotoxic effects also analyzed in the article of interest to us—subclinical alterations—in the fat plaque, while the disease progresses silently—and the outcomes of human interest (stroke, heart attack, death). We will continue an old and cherished dialogue between observations and explanations.

The number of participants (257) and the years of follow-up (less than four) might seem low and might have led to the rejection of the article by the journal. It would not have been justified, as in medicine there are no rigid 'thresholds' to cross: it depends on the magnitude of the observed effect. If the effect is strong, modest numbers of participants and time are sufficient. And these numbers were sufficient this and many other times to calculate relevant effects with good precision, like the aforementioned 4.5.

"Sometimes what is not ethical is not investigating"

Another attractive line for the public interested in the sciences is that the Neapolitan study is a clear example of a problem in which it is neither ethical nor feasible to conduct a randomized clinical trial, that type of study in which researchers randomly assign who receives the exposure (in this case, MNP) and who does not. Isn't it obvious? Obviously, it would neither be ethical nor feasible to decide at random who is protected and who is exposed to plastics...

Therefore, for decades we have known that when a randomized clinical trial is not feasible or ethical, the alternative—in medicine, public health, economics, education, and beyond—are observational studies, those without random allocation of exposures of interest. Paraphrasing Sir Austin B. Hill (1897-1991), we say that "sometimes what is not ethical is not investigating." And we know well that relevant knowledge accumulates through different types of observational and experimental studies. It is certainly so when many causes of human diseases concern us.

We know well that relevant knowledge accumulates through different types of observational and experimental studies

Ah, yes: the usual thing in observational studies conducted in many sciences is that the people who are exposed to the factor of interest (in our case, MNP) are somewhat or quite different from those who are not. Could part of the clinical effects observed and attributed to plastics be due to these differences? In the Italian study, patients were classified into one exposure group or another (with or without detectable levels of certain MNP) after analyzing the atherosclerotic plaque. And compared to those without plastics in the excised plaque, people whose plaques contained MNP were younger; they were more often men or smokers; and less frequently, hypertensive, diabetic, affected by cardiovascular diseases, or dyslipidemias. Today, these differences do not represent a notable methodological problem, and the possible biases induced by them are well controlled, as diligent researchers use quantitative analysis techniques that take into account or adjust for these differences. As did the authors of the article we are discussing: the aforementioned figure of 4.5 is adjusted and neutralizes the differences.

The study will incentivize similar ones

It is important that more health professionals and communicators are up to date regarding the advances we have achieved in the last three decades on the symbiosis between experimental and observational studies. Thus, for example, about the knowledge gained with target clinical trials, conducted before and during the latest pandemic in real-time and in real populations through observational studies that deal with differences between exposure groups or with temporal changes in the lives of participants, and that apply other methodological strategies still little known by many disseminators.

Without this methodological rigor, the study would not have been published in the NEJM. Period. It is important to emphasize this in the face of some attempts to discredit part of the research in medicine and epidemiology. Nor would we read it in that journal without the courage and creativity in which its hypothesis was forged, without its technical innovation or the potential relevance of its findings for clinical medicine, public health, and the fundamental sciences on which one and the other are based.

The good thing is that publication in NEJM makes visible, legitimizes, removes, and will incentivize other similar works

But, be careful: it has indeed been a small surprise that NEJM accepted the article, as it usually publishes little on the environmental causes of human diseases. In principle, the most likely scenario was that the article would have been accepted in one of the D1 journals of epidemiology or environmental health, those in the top decile (top ten percent) in terms of the most common bibliometric influence indicator. Although its planetary echo would have been much smaller, the article would have been essentially the same. What matters least is that many articles as good as the aforementioned appear in less-known journals outside those of us who work and publish in them, often led by professionals of great scientific and human quality, like José Luis Domingo. The good thing is that publication in NEJM makes visible, legitimizes, removes, and will incentivize other similar works. Editors like Caren Solomon in NEJM or Jody Zylke in JAMA are models from which other doctors and journals—and young students—draw inspiration to overcome barriers and epistemic closures (what topics it is preferable to avoid, what is scientific, what is causal, what is harmless and comes to us for free). Working from Spain, Sweden, or the United States, Ana Navas Acién, María Téllez Plaza, Carolina Donat Vargas, or Jordi Bañeras have also published excellent empirical studies, using contamination biomarkers like Marfella, on the environmental causes of cardiovascular diseases. It is not honest to opine on those causes without having studied them.

And it is not trivial: "The plastics crisis has grown insidiously while many eyes were on climate change," says Philip Landrigan in the editorial accompanying the Italian article. "Plastics endanger human health at all stages of the plastic cycle," Landrigan adds. Fossil fuels (gas, oil, coal) are the main raw materials for plastics. Much power. There is abundant evidence that the most reactionary and extremist populism—the least conservative—is more resigned to us connecting plastics and the climate crisis, out there, than plastics and health: in here, in the greasy light of the carotid arteries.