Where in Spain is there the highest risk of jellyfish?

“It is much more common to see jellyfish on the Mediterranean coasts than on the Atlantic ones,” explains Laura Prieto, a biological oceanographer at the Institute of Marine Sciences of Andalusia (ICMAN-CSIC), to the SMC Spain.

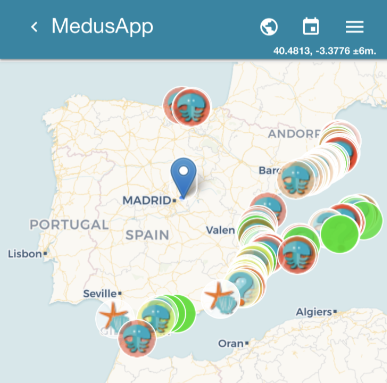

This trend can be confirmed with a simple search on the map of MedusApp, an app designed by the University of Alicante that allows users to report the presence of jellyfish on the coast.

According to Lucrecia Souviron, who works in the Alborán Sea environment, is a member of the Biogeography, Diversity and Conservation Group at the University of Malaga and also works as a biologist at the Aula del Mar Mediterráneo Foundation (FAMM), this difference between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic coasts could be due to high tide and easterly winds, which increase the surface temperature of the water, attracting jellyfish to the coast.

However, it should be noted that most jellyfish are not on the beaches but a few miles offshore, as recalled by a jellyfish campaign carried out in 2010 by the then Ministry of Environment and Rural and Marine Affairs. Also, the arrival of these marine animals to the coast depends on many factors.

One of them is the water temperature, which “activates the jellyfish gonads.” “They like it when the water is warm, causing them to proliferate more than usual and, therefore, increasing the likelihood that they are present on the beaches during the summer months,” explains Souviron to the SMC Spain. However, according to the expert, who also has a PhD in biology, other local factors such as currents, wind direction, and tides, play a role as well.

For example, in the Alboran Sea, the main current is made of two adjacent anticyclonic gyres that usually “trap” the Mauve stinger (Pelagia noctiluca). But these gyres can lose intensity, leaving the jellyfish free to approach the beach in search of nutrients. “This is what is believed to have happened in the province of Malaga during 2018, where tons of jellyfish were removed in the three months that the summer season lasted,” recalls the researcher.

Are there more in recent years?

It is not entirely clear. In the 1990s, the idea that jellyfish populations were increasing due to the degradation of the oceans became popular. However, one of the most extensive analyses conducted, which included global data from 1790 to 2011, dismissed this theory.

According to the study, published in 2012 in the journal PNAS, jellyfish populations fluctuate approximately every 20 years, which would align with the increase observed in the 1990s, which coincided with the rise of one of these cycles. According to Prieto, “there are not more jellyfish now than before.”

Twelve years after the publication of that study, today the effects of climate change are evident in some temperate seas, and in certain areas, the local increase in jellyfish is associated with human interventions, such as overfishing or oil spills, as warned by studies in 2007 and 2009.

One of the effects of climate change is the increase in sea temperature, which “would be positively correlated with the proliferation of jellyfish,” according to Souviron. However, as pointed out in an article by Mark Ohman, a biological oceanographer and curator of the Pelagic Invertebrates Collection at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego (USA), “warmer waters often favor jellyfish growth, but only if they have enough food.” That is, if krill larvae or fish eggs decrease with warmer water temperatures, these animals would also decrease.

A characteristic of jellyfish is their high resilience. “Experiments conducted demonstrate the high plasticity of these organisms,” Prieto points out, referring to a study that shows that Cotylorhiza tuberculata is capable of surviving in extreme conditions. According to this research, and considering that some types of jellyfish tolerate very low oxygen conditions, some species could adapt to the pressures of climate change.

Are there jellyfish only in summer?

No. According to Souviron, there are specimens that can be seen all year round, like the Mauve stinger, although usually, in Spanish waters, there are more jellyfish in spring and summer because most species are seasonal, meaning that they remain in polyp or resistant egg form during the rest of the year. For example, “the fried egg jellyfish (Cotylorhiza tuberculata) tends to be more abundant in late summer and early autumn,” explains the researcher.

How do I know if there are jellyfish in an area?

There is a white flag with a jellyfish drawn on it. “If lifeguards hoist it, it means there are jellyfish on that beach,” indicates Souviron. This flag, which can vary depending on the area, “is raised if the jellyfish incidence is medium-high,” points out Prieto, although it is also usually accompanied by a yellow or red flag depending on the quantity and danger of the jellyfish. The meaning of these flags is the usual: the red flag prohibits swimming, and the yellow one allows it with caution.

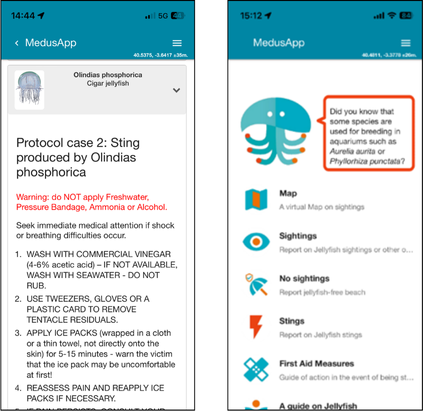

Another way to know if there are jellyfish in an area is through apps like Infomedusa, from the ‘Aula del Mar Mediterráneo’ foundation, or MedusApp. Both include updated maps with the presence of these marine animals on the coasts. Additionally, they allow users to report new sightings in real-time and offer useful information about first aid or the danger of different specimens.

Why do they "sting"?

“Jellyfish don’t sting,” clarifies Mar Fernández Nieto, a member of the Asthma Committee of the Spanish Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (SEAIC). “They cause hives,” she adds. Jellyfish have a defense system, with cells (cnidocytes) that cause itching and rash on the skin of their prey.

These cells contain a venom that is injected through a filament with spines. Nuria Navarro, associate professor and coordinator of the Coastal and Marine Zones Research Group (ZOCOMAR) at Rey Juan Carlos University, compares it to a harpoon. “When the jellyfish tentacles come into contact with an animal, the cnidocytes fire and stick their harpoon into the skin, releasing the venom,” she explains to the SMC Spain.

What injuries do they cause?

As noted in this campaign by the then Ministry of Environment and Rural and Marine Affairs, initially, there is usually an intense and sharp pain (similar to a bee sting or a burn) in the area that has been in contact with the jellyfish. But the pain and intensity of the reaction can vary depending on the species' danger, the number of "stings" produced, or the affected area (greater in children).

Usually, the injury disappears within a few days, but the discomfort can persist for weeks or months in more severe cases. According to Fernández Nieto, these reactions can be more severe if one suffers from heart, kidney, or respiratory diseases like asthma, as sensitivity can vary from person to person.

Therefore, the researcher recommends consulting a doctor immediately for “any exaggerated reaction over 10 centimeters at the contact site, or [any] sting accompanied by general symptoms like hives, dizziness, or vomiting.”

If there are jellyfish on the beach, how do I avoid getting stung?

Navarro gives three recommendations to avoid problems with these marine animals: “Do not swim, avoid areas where waves break as they tend to accumulate there, and protect your skin from any contact with jellyfish by wearing swimsuits, shirts, or other clothing.”

In the jellyfish campaign by the then Ministry of Environment and Rural and Marine Affairs, it is also recommended the use of sunscreen, as it has some capacity to protect us from jellyfish tentacles. Under no circumstances should you touch jellyfish, “even if they seem dead,” the researcher clarifies, as the 'sting' occurs upon contact with our skin, whether they are alive or not.

As for the Ministry of Health, they warn that the main thing is not to underestimate the situation and to heed health recommendations. If there are jellyfish on the beach, it is not advisable to walk, play, or swim at the shore. “Broken pieces of jellyfish, usually tentacles, can reach the shore and still sting,” explains Navarro. It is also not advisable to cool off by collecting water with a bucket. “In the water, there can be very fine tentacle remnants that we cannot distinguish with the naked eye,” she adds.

What should I do if I get stung?

The recommendation of the Ministry of Health is to notify the lifeguard as soon as possible, as well as:

- Wash the area with salt water, without rubbing. Freshwater should not be used, as the jellyfish cells could burst and spread more venom.

- If there are tentacle remnants on the skin, they should be removed with tweezers, not with the hands.

- To relieve pain and reduce inflammation, cold can be applied to the affected area. But not for too long (about 15 minutes).

- During the first few days, it is important to disinfect the wound with iodized alcohol two to three times a day. Additionally, to treat the reaction, “a corticosteroid cream can be applied or an antihistamine taken,” adds Fernández Nieto. But “always under medical prescription,” she emphasizes.

Lastly, the Ministry stresses that people with allergies, children or the elderly may need special attention. If symptoms such as nausea, dizziness, muscle cramps, headaches, or general malaise appear, one should go to the hospital and report the type of jellyfish that may have caused the sting. If the reaction is large, Fernández Nieto believes that an allergologist should be consulted, as “there is an underdiagnosis of non-toxic allergic reactions from jellyfish stings.”

Although other remedies, such as vinegar or urine, have become popular to soothe irritation, not all of them are equally recommended. In theory, these substances work in two ways: the pressure of the liquid cleans any jellyfish remnants that may left in the area, and the acidity neutralizes the toxins in the venom.

However, as explained by the American Chemical Society in an informative video, urine is not suitable for doing either function. It is a liquid that contains very few salts and, just like fresh or tap water, it will enter and activate the stinging cells, worsening the reaction. In addition, urine is not acidic enough to neutralize the toxins produced by most jellyfish.

Vinegar, on the other hand, is much more acidic and could be an option for treating some stings, although its effect is limited and will depend on the type of toxin produced by each jellyfish.

What are the most dangerous species we can find on Spanish coasts?

According to Fernández Nieto, “in Spain, there are no sightings of jellyfish with deadly toxicity, but in many cases, reactions can be severe.” Therefore, prevention is crucial.

“In Spain, the species that causes the most painful sting is the colony of organisms Physalia physalis,” notes Prieto. This species, also known as the Portuguese man o’ war, leaves a mark wherever the skin has come into contact with the jellyfish’s urticating cells. The large number of stinging cells it has and the potency of its venom, which has neurotoxic, cytotoxic, and cardiotoxic properties, produce such intense pain that it can lead to neurogenic shock and drowning.

However, not all jellyfish are equally dangerous. “There are many species that are not dangerous,” explains Navarro. For example, Cotylorhiza tuberculata (fried egg jellyfish), Aequorea forskalea (Aequorea jellyfish), or Aurelia aurita (common jellyfish) “have little to no capacity to produce hives, with little or no effect on human health,” she points out.

For more information on the danger of different types of jellyfish, you can consult this guide through the MedusApp application.

Despite the inconvenience, why are these marine animals important?

Souviron highlights their relevance to marine ecosystems: they provide shelter for small fry, serve as food for some animals, and when they die, they release essential nutrients that help maintain the ocean's food chain, among other things. “There are some sea turtles whose diet is almost 100% based on jellyfish, such as the leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea),” she explains.

Additionally, the scientist believes that “they can (and are) providing valuable information about the health of the marine ecosystem and the impacts of climate change.”

Furthermore, jellyfish are an enormous source of bioactive substances. This 2011 study describes more than 3,000 active substances derived from the Phylum Cnidaria group, which includes jellyfish and encompasses more than 11,000 marine species. All these substances could be used to develop new products and treatments, so their value to the cosmetic and biomedical industries is incalculable.

In some countries, they are also relevant to the food industry. In Japan, for example, the buying and selling of jellyfish has become a multimillion-dollar market, as indicated by this 2001 publication.