New evidence confirms that the oldest known hominid walked on two legs 7 million years ago

A US research team presents new evidence in Science Advances that Sahelanthropus tchadensis was a biped that evolved from an ape ancestor. Based on the study of two partial ulnas and a femur, they conclude that S. tchadensis—the oldest known hominid, which lived around 7 million years ago—had bones similar in size and shape to those of chimpanzees, but with a relative proportion more similar to that of hominids.

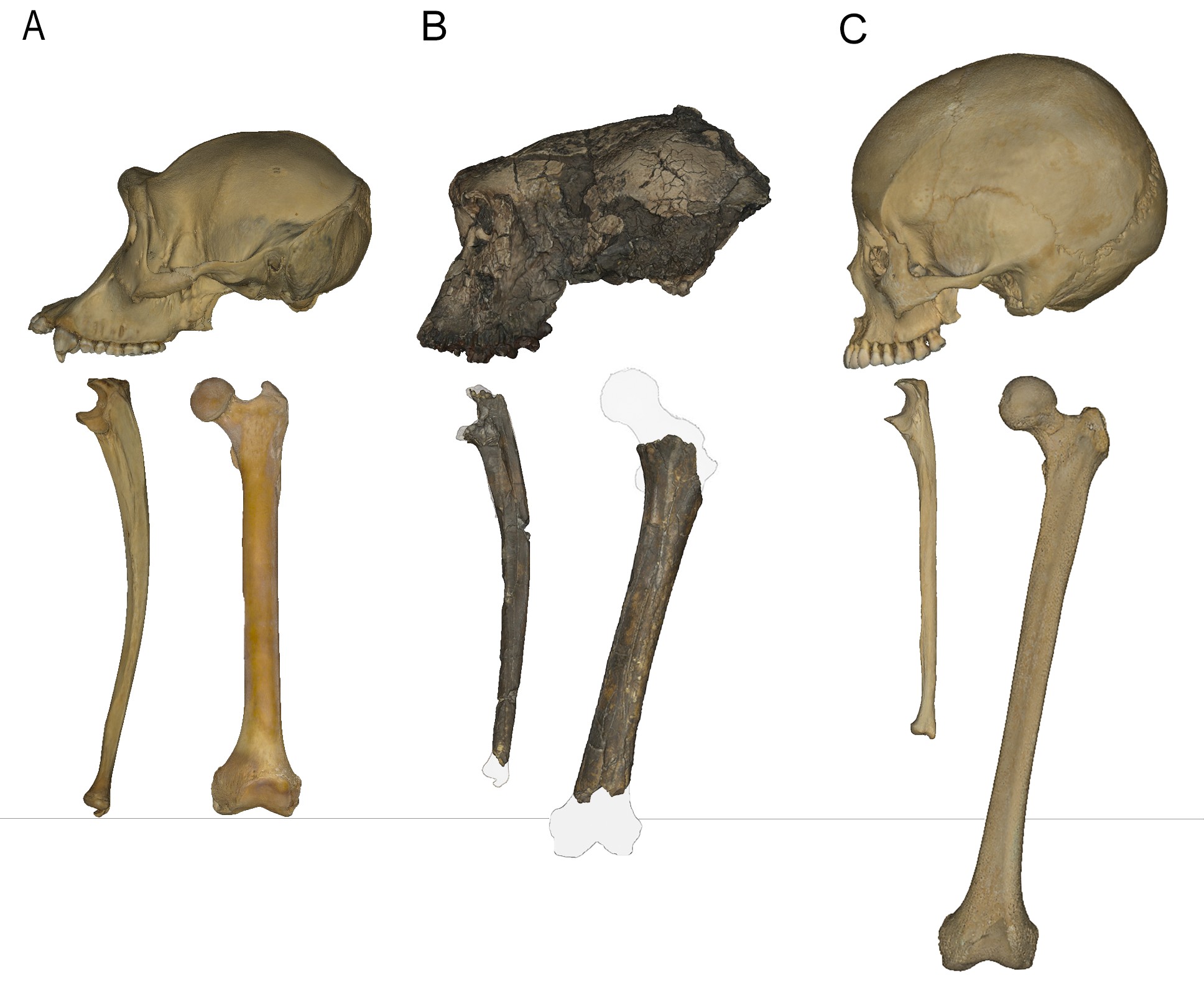

S. tchadensis fossils (TM 266) compared to a chimpanzee and a human. Credit: Wiliams et al., Sci. Adv. 12, eadv0130

Josep Maria Potau Ginés - bípedo EN

Josep Maria Potau Ginés

Researcher in the Human Anatomy and Embryology Unit of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at the University of Barcelona

The study is based on solid data and methods and is included in various previous works that defend or criticise the presence of bipedalism in Sahelanthropus. The main new findings are the description of an anteversion of the femoral diaphysis, which may be related to the presence of a bicondylar angle in this bone, and the description of a well-developed femoral tubercle. Both anatomical features are related to bipedal locomotion. The main limitation is that the anteversion and femoral tubercle have been described in an incomplete femur.

In practice, the relevance of this article is that the demonstration of bipedalism in Sahelanthropus would be the oldest known, placing it very close to the evolutionary split in the two lines that gave rise to chimpanzees and humans.

Sahelanthropus tchadensis is one of the fossil primates potentially located in the evolutionary line of the oldest known humans. Its fossil remains have been dated to about 7 million years ago, but its bipedal locomotion, a determining factor in placing a fossil primate within the evolutionary line of Homo sapiens, has not been clearly demonstrated. Some authors defend the bipedal locomotion of this primate based on the anatomy of the femur (Daver et al., Nature 2022), while others find no relationship between the bone morphology of the postcranial skeleton of Sahelanthropus tchadensis and bipedal locomotion (Cazenave et al., Journal of Human Evolution 2025).

This article by Williams et al. in Science Advances (2025) presents new evidence pointing to possible bipedal locomotion in Sahelanthropus tchadensis, based mainly on femoral anatomy. The presence of an anteversion in the femoral diaphysis, which can be related to the presence of a bicondylar angle in this bone, an anatomical feature typical of bipedal primates such as Homo sapiens, as well as the presence of a well-developed femoral tubercle, are novel evidence that would support the presence of bipedal terrestrial locomotion in this fossil primate.

The development of bipedalism in Sahelanthropus tchadensis, shared with other types of common arboreal locomotion, would support the position of this fossil primate in the evolutionary line of humans, placing it very close to the common ancestor from which the two evolutionary lines that gave rise to chimpanzees and modern humans originated some 7 million years ago.

José-Miguel Carretero Díaz - bipedismo EN

José-Miguel Carretero Díaz

Professor of Palaeontology and Director of the Human Evolution Laboratory at the University of Burgos

"Since the beginning of this century, to round things off, bipedalism has ceased to be one of those “magical” traits that defined hominins (humans and our fossil ancestors). The discoveries of Ardipithecus ramidus (4.5-4.3 million years ago) and Ardipithecus kadabba (5.8-5.2 million years ago), and their inclusion as part of our group, have shown that orthograde, terrestrial, and obligate bipedalism only appeared a few million years later with the emergence of the famous Australopithecus, around 3.9 million years ago. In the latter, we find, from head to toe, all the anatomical transformations necessary to be an orthograde, habitual, obligate, and efficient biped.

Ardipithecus was only an optional biped, that is, an arboreal quadruped that had the ability to move on the ground on two legs with some ease, which it did only occasionally. Incidentally, many primates, especially our closest relatives, orangutans, gorillas and chimpanzees, have the same ability and also exercise it with some ease on occasion. Ardipithecus would be another facultative biped, although we must acknowledge certain anatomical changes in its hips that surely allowed it to be somewhat more efficient than the three great apes. This must have been an adaptive advantage that natural selection did not overlook, and that is why we are here today. To this we must add that the idea that ‘bipedalism arose only once and that there is only one type of bipedalism’ does not seem to fit with what we know from the fossil record, nor with what we would expect from an evolutionary point of view, where, when faced with a new ecological niche, natural selection usually generates different adaptive possibilities, of which, over time, many, few or none at all.

The discussion is therefore no longer “bipedal vs. non-bipedal”, but rather what type of bipedalism Ardipithecus and other possible hominins such as Orrorin tugenensis (6 Ma) or Sahelanthropus tchadensis (7 Ma) might have had. Unfortunately, the postcranial skeletal remains of these latter two species are so scarce that it is very difficult to address or shed light on this question.

Is the study based on solid data and methods?

Since their discovery, studies of the three postcranial remains of Sahelanthropus (two highly fragmented ulnas and a femur) have been the subject of heated controversy, from their dubious association with the skull itself to the details of their anatomy or whether they belong to the same individual.

In my opinion, the work presented is commendable in that it attempts to highlight and interpret very subtle morphological differences in highly fragmented and altered remains. This is the work of palaeontologists, to extract insights from scarce and poorly preserved remains. To this end, geometric morphometric analyses are a powerful and always useful methodology, and regression models are appropriate for making certain estimates. However, it is one thing to highlight subtle differences between fossil specimens and quite another to make functional interpretations of locomotor behaviour and evolution that, in my opinion, exceed what can really be gleaned from these subtle differences. In this work, these interpretations are, at the very least, extremely risky and sometimes contradictory. For example, the general title and the short title at the beginning of the work leave no room for doubt: ‘Sahelanthropus was bipedal’ [in Spanish]. However, throughout the paper and in the discussion, the authors make it clear that Sahelanthropus was most likely a forest dweller with a varied locomotor repertoire (vertical crawling, brachiating, quadrupedal on branches, terrestrial quadrupedal, etc.), just like Ar. Ramidus, according to them. In other words, just another facultative and occasional biped.

That is why I find the title of the paper reckless and it gives the impression of being designed more as a headline for the general public than as a reflection of reality based on the data presented.

How does it fit in with previous work? What new information does it provide?

"The anatomical evidence presented is not, in my opinion, sufficiently solid to support the study's categorical conclusions about bipedalism or the mode of locomotion of Sahelanthropus. I have the impression that the anatomy is being twisted to fit preconceived ideas. The conclusions of this study are clear: ‘the limb bones of Sahelanthropus are similar to those of a chimpanzee,’ as are its habitat and locomotor repertoire, and other authors have reached the same conclusion in previous work on these same remains.

In this sense, I do not think the work brings much clarity to the issue, as it merely confirms what had already been said. The new feature that, according to the authors, “demonstrates” adaptations for bipedalism is a small “bulge” visible on an eroded and fragmented surface near the proximal fracture of the bone. It is claimed that this “tubercle” demonstrates the presence of a human-like iliofemoral ligament and therefore that Sahelanthropus was bipedal. Without going into detail, even in later Australopithecus, which show all the skeletal adaptations of an efficient biped, it is debated whether this ligament had the same configuration as in humans and whether its function was therefore the same.

Are there any important limitations to consider?

"In addition to the new “tubercle”, the features mentioned as characteristic of bipedalism (intermembral proportions, femoral torsion, bicondylar angle, etc.) are based on estimates and assumptions that are not justified, beyond the personal opinion or preference that each individual may have. Therefore, this work seems to me to be more a statement of intentions and opinions than a set of data that demonstrates what the title claims. The reconstruction of missing parts, intra- and interspecific variation, and functional inferences based on similar morphologies are challenges that are always subject to discussion, review, and improvement. All the features that are noted as unique to bipedalism have been discussed in detail by various authors, and the conclusion is that they are not sufficiently informative to establish a clear locomotor model for Sahelanthropus. The final conclusion of this work is that it would be, by assimilation, something similar to the model of Ardipithecus.

In the words of the first author, Scott Williams: ‘Sahelanthropus tchadensis was essentially a bipedal ape ... that probably spent much of its time in trees, seeking food and shelter’ [in Spanish]. In my opinion, it should be said that Sahelanthropus is essentially an arboreal primate, a forest dweller and, like many other hominoids, including the great apes, occasionally a facultative biped on the ground. It remains to be seen whether it was as effective as a chimpanzee, Ardipithecus or Australopithecus.

In addition, there are other more fundamental limitations, and advances are still needed on several fronts. First and foremost, of course, is the need for a better fossil record. But also, for example, a better understanding of locomotor and postural patterns in non-human primates, a better understanding of how bone morphology reflects different modes of locomotion, difficulties in assessing the proportion of different locomotor repertoires in primates, and the challenge of reconstructing a form of bipedalism different from our own that we do not label as “imperfect”.

How relevant is this study in practice?

‘There is no denying the importance of this fossil record and that knowledge of it can shed light on the origin of bipedalism, but in practice, this work does not provide compelling and defensible evidence that can generate consensus among specialists.’

There is debate in this area of research. Does this study resolve it?

‘In my opinion, it certainly does not resolve the debate on the origin of bipedalism because, in reality and unfortunately, the remains found so far are not sufficiently informative, hence the controversy and debate they provoke. If the same fossils can be used to say one thing and its opposite, then they are surely insufficient.’

Scott A. Williams et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed