Genomic analysis clarifies the chronology of Neanderthal-modern human admixture and its genetic impact on our species

A team of researchers has analyzed more than 300 human genomes from the last 50,000 years and has concluded that most of the gene flow we received from Neanderthals is attributable to a single period, which probably occurred between 50,500 and 43,500 years ago. In addition, Neanderthal inheritance underwent rapid natural selection in subsequent generations, especially on the X chromosome, according to a study published in Science.

Marín - Neandertales (EN)

Ana B. Marín Arroyo

Full Professor of Prehistory and Director of the EvoAdapta Group at the University of Cantabria

In recent years, paleogenetic studies are providing higher resolution data on one of the most relevant periods of our evolution, which is the decline of Neanderthal populations and the emergence of our species. Early paleogenetic studies already showed that we had fertile offspring with Neanderthals and that Neanderthals also hybridized with Denisovans, something that is not visible in the record of human fossils found so far.

This work published in the journal Science confirms that there was a single gene flow from Neanderthals to the first representatives of our species in Europe between 50 and 43,000 years ago, confirming what archaeological evidence already indicated about the spatio-temporal coincidence of both species on the continent. In addition, it sheds light on how different Neanderthal genes related to skin pigmentation, the immune system or metabolic development could have been beneficial for our health and biological adaptations to a climatically unstable environment.

In short, this study confirms genetically the moment of interaction between Neanderthals and our species at the end of the Pleistocene and how their genes have left a permanent imprint on what we are today as a species.

Fox - Neandertales (EN)

Carles Lalueza-Fox

Director of the Museum of Natural Sciences of Barcelona and specialist in DNA recovery techniques in remains from the past

The main novelty of the study is to constrain the Neanderthal admixture episode very precisely to less than 50,000 years and to confirm that all modern humans today show the signs of this same episode.

The most interesting consequences derive, however, from other collateral aspects; first, since humans in Asia and Australasia, who have signs of admixture with Denisovans, also have the common Neanderthal signal, that means that the same episode with Denisovans is still more recent. And second, since there are fossil remains attributed to modern humans in Asia (not only in China, but also in Laos and the Philippines) earlier than 50,000 years ago, these must correspond to an earlier departure out of Africa that, for reasons unknown to us, did not leave genomic traces in present-day humans.

Surely the most interesting thing for the future would be to try to recover DNA from some of these early Asian Homo sapiens, to understand how they differed from those who left Africa a few tens of thousands of years later. Even if they did not reach the present day, it would be interesting to know if they also interbred with Neanderthals or Denisovans. The picture of this period in Asia is certainly complex and I think it needs to be explored as a whole.

Rosas - Neandertales (EN)

Antonio Rosas

Research professor in the Department of Paleobiology at the National Museum of Natural Sciences, CSIC

This work addresses the phenomenon of hybridization between Neanderthals and modern humans. It is a study that includes a large volume of genomic information data, both from current populations and, more importantly, from humans of the past. The work, very solid in its structure and development, confirms a number of previous results related to:

- The timing of hybridization (between 50,500 and 43,500 years ago).

- The number of hybrid events (only one in populations after 40,000 years ago).

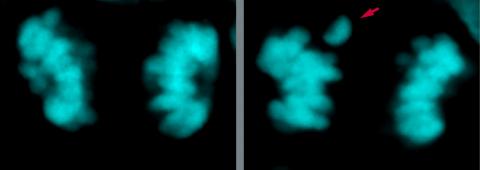

- The effect of the conservation of Neanderthal genes in our chromosomes.

This last point ratifies the idea that the negative selection (elimination) of Neandertal chromosomal segments occurred very quickly, immediately after the hybridization event. This sweep of Neanderthal inheritance in our chromosomes gave rise to the so-called 'genetic deserts'. On the other hand, and in the opposite direction, it is confirmed that all humans of non-African origin retain between 1% and 2% of Neanderthal DNA, whose functions are essentially related to skin pigmentation, metabolism and the immune system.

Iasi et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- People