What is the Oropouche virus and what kind of disease does it cause?

The Oropouche virus (OROV) is an arbovirus of the genus Orthobunyavirus, belonging to the family Peribunyaviridae. The disease it causes, known as Oropouche fever, is a febrile infection that is transmitted mainly through the bite of the Culicoides paraensis midge, an insect smaller than a mosquito that lives in wooded areas and near bodies of water. It can also be transmitted by certain mosquitoes such as Culex quinquefasciatus.

The disease's transmission cycles are suspected to include both jungle and urban cycles. In the jungle cycle, primates, sloths and possibly some birds act as vertebrate hosts. In the urban cycle, humans are the amplifying host.

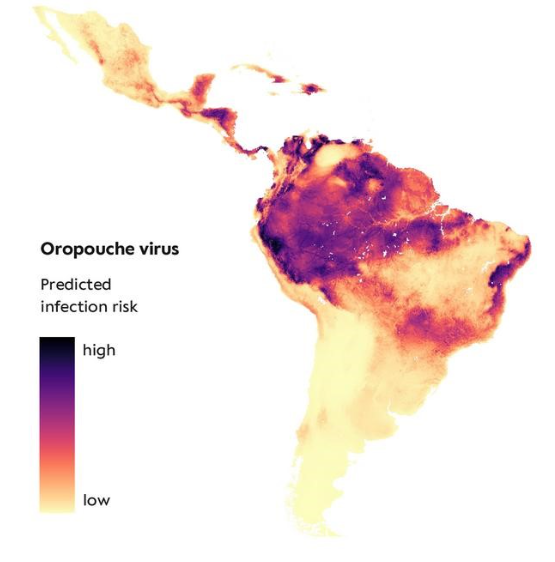

In addition, climate change and its consequences are key factors in the increased spread of the disease in both transmission cycles. Intensified rainfall and temperatures, as well as deforestation and urbanisation, have altered the natural habitats of vectors and hosts, favouring interaction between them and increasing the risk of transmission. This is identified in an article published in the Journal of Travel Medicine, which also warns of the consequences: ‘Viruses previously confined to tropical regions are expanding their geographical range and establishing indigenous cycles in new areas.’

Where has the disease been detected and in which regions is it currently present?

The virus was first identified in 1955 in the Caribbean country of Trinidad and Tobago and has caused cases and outbreaks in several South American countries, including Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela. Outbreaks have been more frequent in the Amazon basin region, where the best-known vector, the midge Culicoides paraensis, has a jungle transmission cycle.

The Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) warned on 2 February 2024 of an increase in the detection of Oropouche fever cases in some areas of the region of the Americas. Since then, PAHO has issued successive epidemiological alerts, updating the affected areas and providing new information on its development, the latest on 13 August.

However, official data may not reflect the true extent of the virus's spread. A study published last April in The Lancet Infectious Diseases highlights that OROV infections in Latin America are being underdiagnosed, and its authors suggest that incidence data may be skewed by geographical disparities in diagnostic testing.

They therefore warn that areas where no cases of the disease have yet been reported are not exempt from the threat of the virus spreading: ‘Regions with no known circulation of OROV are at risk of becoming endemic.’

Is there a risk that it will reach Europe or Spain?

Jacob Lorenzo-Morales, director of the University Institute of Tropical Diseases and Public Health of the Canary Islands, explains to SMC Spain that currently the main vector that transmits the disease—the Culicoides paraensis midge—is not present in Europe. However, the expert explains that this cannot be ruled out entirely, citing the spread of the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) as an example: ‘Invasive vectors are adapting and spreading worldwide, so in this case it could happen.’

For his part, Agustín Benito, director of the National Centre for Tropical Medicine (CNMT) at the Carlos III Health Institute, also warns of the spread of the disease to non-endemic areas as a result of ‘climate change, deforestation and increased movement of people’. Despite this, the director of the CNMT points out that ‘the risk of local transmission in Europe is currently very low’ and explains that, although there have been imported cases associated with travel, no human-to-human transmission has been detected anywhere in the world.

According to PAHO data, there have been 12,786 confirmed cases in Latin America in 2025. Brazil has the highest incidence of positive cases, with 11,888. In 2024, the total was 16,239 positive cases.

As for Europe, in 2025, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) has published a bulletin with the latest data, dated 25 July: Germany reported an imported case in a person who visited Dominica; France reported one imported case in a person who visited Brazil, and the United Kingdom reported three imported cases in citizens who travelled to Brazil.

Last year, there were 44 imported cases in the EU: Spain (23), Italy (8), Germany (3), France (7), Austria (1), Sweden (1) and the Netherlands (1). Of these, 43 cases had a history of travel to Cuba and one to Brazil.

‘The probability of infection for EU/EEA citizens travelling or residing in epidemic areas in South and Central America is currently considered moderate. The probability of infection increases if travellers visit the most affected municipalities in the northern states of Brazil or the Amazon region, or if personal protective measures are not taken,’ the ECDC bulletin states.

What are its most common symptoms and how do they differ from other similar diseases such as dengue or Zika?

As indicated by the World Health Organisation (WHO), the most common symptoms are sudden fever, severe headache, extreme weakness, or joint and muscle pain. These symptoms usually appear between four and eight days after the bite that causes the infection. In some cases, other symptoms may appear, such as photophobia, dizziness, persistent nausea or vomiting, and lower back pain. The fever usually lasts up to five days, and most people recover within a week.

Lorenzo-Morales explains that this disease develops in two phases: ‘The person has a fever and pain for a few days, and then these symptoms disappear, only to return after a week and disappear again.’ This causes the recovery time to be prolonged. According to data from the WHO, up to 60% of cases experience relapses after overcoming the disease.

Benito tells SMC Spain that, in its initial phase, the disease can be ‘clinically intense’ and confused with other tropical conditions. Lorenzo-Morales points out that it is precisely this “relapse” that can differentiate Oropouche disease from others with ‘very similar symptoms’ such as dengue or Zika.

The disease does not usually lead to serious complications, although it can progress to meningitis or encephalitis, which may manifest in the second week of the disease. As the expert explains, these cases are rare and affect ‘less than one in twenty people’ who have the disease.

Is there a treatment or vaccine for the disease?

Currently, there are no specific antiviral drugs or vaccines. Treatment focuses on relieving symptoms and includes rest, hydration, and medication for fever and pain. It is also recommended that patients be kept under observation and monitored for possible complications.

How is it diagnosed?

Currently, there is no rapid test available to confirm the presence of the disease. The diagnosis is confirmed by molecular (PCR) or immunological (antigen or antibody detection) tests analysed in laboratories. Lorenzo-Morales points out that when diagnosing the disease, it is important to bear in mind that the virus is present in the blood for a very short period of time, approximately two days, so samples must be taken during the acute phase of the disease.

Benito highlights the importance of diagnosis in order to rule out other more common diseases with similar symptoms, such as dengue, chikungunya and Zika. The specialist explains that in Latin America and the Caribbean, ‘surveillance networks have strengthened the diagnostic capacity’ for the virus and that in Europe, reference laboratory networks also prioritise differential diagnosis: ‘They have promoted the inclusion of the Oropouche test in cases of tropical fever syndrome with no clear aetiology’.

Is there a risk of complications?

As stated by the PAHO, serious complications are rare in the course of the disease. This is also indicated by the director of the CNMT: ‘The prognosis is good and fatal outcomes are extremely rare.’

However, difficulties such as low blood pressure, intense sweating—which can lead to rapid dehydration—or complications in the nervous system such as meningitis, meningoencephalitis or Guillain-Barré syndrome may occur.

Which groups are most vulnerable to this disease?

Pregnant women are at particular risk of infection: ‘They are the most vulnerable group,’ stresses the director of the CNMT. Although there is no extensive research on how the disease may affect this population group, various disorders have been identified that negatively affect the development of pregnancy.

A study published in Viruses concludes that, based on data up to 2024, pregnant women who have had the disease have experienced miscarriages, stillbirths or the birth of babies with microcephaly.

The authors of another article published in the journal Genes explain that following the epidemiological alert issued by PAHO in July 2024 warning of the association between the Oropouche virus and vertical transmission, it was confirmed that the virus can infect the placenta and the foetus. This could have consequences for foetal development, leading to congenital infections, miscarriages, foetal death or congenital anomalies, including nervous system damage with microcephaly.

To avoid all these risks, Benito stresses the importance of extreme protection for pregnant women through vector control measures and clinical monitoring.

The expert adds that people with chronic diseases or weakened immune systems, as well as the elderly and babies, can also be considered at risk. ‘Although most community cases occur in healthy young adults, it is prudent to take special care of the above-mentioned groups during local outbreaks,’ says Benito.

What preventive measures can be taken, especially when travelling to areas where the virus is circulating?

The WHO recommends that people travelling to areas under health alerts for the disease take precautions against insect bites, using repellents containing icaridin or DEET — N, N-diethyl-meta-toluamide, the main chemical in insect repellents —, protective clothing that covers the arms and legs, and fine mesh mosquito nets over beds or sleeping areas.

The international organisation also calls for vector prevention and control measures to be adopted by strengthening entomological surveillance and reducing sand fly populations.

The authors of an article published last February in Viruses conclude that as Oropouche disease spreads to non-endemic areas, regional and international collaboration will be essential to mitigate its spread and protect vulnerable populations.