What is chronic pain?

Chronic pain can be a disease in itself, as in primary pain syndrome, which includes pathologies such as fibromyalgia; or a symptom deriving from other pathologies, such as cancer, muscle damage or surgery.

In any case, to be considered chronic, the pain must be present - continuously or recurrently - for more than three months.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) differentiates seven types of pain according to their origin and characteristics. Six of them derive from a specific damage that becomes chronic over time, but in the primary chronic pain syndrome the origin is not so clear. In this case, it is the brain that misinterprets the stimuli it receives and becomes more sensitive to pain, which makes it very vulnerable to social and psychological factors such as fear, socio-cultural context or economic level.

In the long term, chronic pain may also increase the risk of other pathologies, such as cancer, cardiovascular or respiratory diseases. In addition, this type of pain often generates feelings of helplessness, hopelessness and anxiety, and even triggers or aggravates disorders such as depression, explains to SMC Spain Mayte Serrat, who holds a PhD in Psychology, is a physiotherapist and member of the Psychology and Pain working group of the Spanish Pain Society (SED).

How does it work?

Pain is part of the body's alarm system. Its purpose is to protect you from harm or risk, but it is not always proportional to the severity of the situation, just as burning toast can set off a fire alarm, as the Toronto Academy of Pain Medicine Institute of Canada (TAPMI) compares.

In normal situations, pain receptors (nociceptors) detect warning signs throughout the body and transform them into chemical signals (neurotransmitters), which travel to the spinal cord and cerebral cortex. Once there, the brain interprets them according to other signals and functions of the body. If, in doing so, the brain feels it must protect the body, it sends a signal back to the body to feel pain.

As TAPMI points out, this process has a limitation: if, in putting these signals into context, the brain misinterprets the story, it may end up ignoring the damage or generating pain unnecessarily.

Therefore, other factors, such as emotions, the meaning we give to pain or bad experiences, can modulate the way the brain interprets painful signals. This peculiarity may be natural and one-off. ‘A mother who has to save her child or a footballer who can score the winning goal does not feel pain,’ Milena Gobbo, a psychologist and expert in pain and rheumatic diseases, tells SMC Spain.

But in some cases, such as in primary chronic pain syndrome or fibromyalgia, this can lead to a generalised and permanent sensitisation. ‘Anxiety and fear turn up the volume in the brain. Not just from pain, but from every rub or stretch on the skin,’ Amanda C de C Williams, a specialist in chronic pain and Professor of Clinical and Health Psychology at University College London (UK), explains to SMC Spain. This is why education and psychology are effective strategies for managing some types of pain.

Why is it a public health problem?

Chronic pain affects 20% of the Western population - one in five people - according to IASP estimates. In Spain, the Ministry of Health considers the incidence to be somewhat lower, between one in six and one in nine adults.

The problem is particularly serious in children, for whom it is one of the main causes of morbidity, according to the WHO. In fact, the Spanish Group for the Study of Paediatric Pain estimates that it could affect almost one in three children in Spain.

On the other hand, the treatment of chronic pain is complex and requires specialised pain units with professionals from different areas (psychology, medicine, rehabilitation, physiotherapy, etc.), which is not always the case.

In 2022, the IASP published a briefing paper on inequalities in pain management. The text denounces that inequality is present all over the world and that it depends on factors such as race, sex, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status and age.

This inequality also affects Spain. In 2011, a report by the Ministry of Health on pain treatment units found that chronic pain is undertreated and undervalued, especially in paediatric patients.

The document blames the problem on a lack of care and training, which leads to disproportionate use of medication and encourages cultural biases that stigmatise the patient and complicate pain management.

‘It is easy for many to label pain as ‘psychological’ or ‘emotional’ when they cannot justify it, which is naturally unhelpful and disabling for many patients,’ says Williams, who is also editor of the scientific journal PAIN.

According to a 2019 Pain Alliance Europe survey of chronic pain patients in Europe, between one-third and two-thirds of respondents feel stigmatised by their status as a patient or caregiver. As an IASP report explains, these stigmas lead to loss of economic capacity, productivity and quality of life.

Can pain be measured accurately?

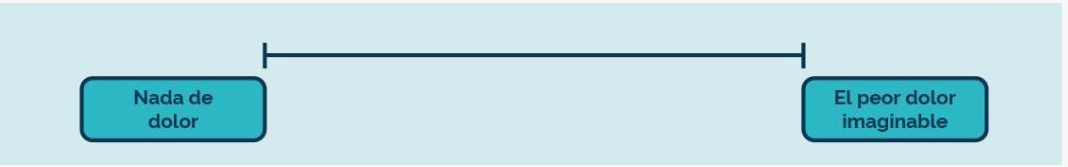

The usual practice is to measure pain with objective assessment scales such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and then supplement that measurement with more comprehensive questionnaires such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire, which also measures other psychological and social aspects of pain. ‘But there is always a margin of uncertainty in the response itself and how it is received by the clinician,’ says Williams, who believes that reporting pain during the consultation is a personal interaction that depends on a range of expectations and social norms.

This margin of uncertainty makes measurement vulnerable to inequality, cultural biases and lack of training of practitioners, who tend to stigmatise the patient when objective findings are not found or pain persists despite treatment.

For example, ‘there is a widespread belief (without any evidence) that women and people from many non-white populations tend to dramatise and exaggerate their response’, explains Williams in reference to a recurring argument that is also contradicted by the IASP fact sheet.

The researcher reminds us that the problem does not only affect women, something that the IASP also points out. ‘Some people are afraid of what will happen if they recognise how much pain they are in and report it less’, she points out, adding that the pain of the elderly, ethnic minorities or people who have suffered mental health problems is also taken less seriously.

Are there differences between men and women?

Chronic pain is more common in women than in men This is shown by numerous epidemiological studies, such as a recent article on gender differences in musculoskeletal pain, or an editorial published in eClinicalMedicine in March 2024.

On the other hand, both gender and sex can alter pain perception. The most studied difference is caused by steroid hormones (oestrogens, progesterone and androgens), which can alter pain sensitivity or influence other processes and diseases such as inflammation or endometriosis. Furthermore, according to the IASP, gender is linked to psychological and social factors that influence the experience of pain.

‘The first thing is to be aware of our gender blindness,’ Ana M. Peiró, a doctor specialising in pharmacology and pain, professor at the Miguel Hernández University and coordinator of the SED's Bioethics working group, told SMC España.

According to Peiró, who also coordinates the Neuropharmacology Research Group applied to pain at the ISABIAL Foundation, gender differences in these ailments have historically received little attention, so that ‘they are coined as conditions of unknown aetiology and become psychological problems’, which has led to less research and diagnostic or therapeutic delays.

Finally, it should be noted that these inequalities do not occur in isolation, but intersect with other factors that generate inequality, such as poverty, educational level, violence and childhood trauma.

How is chronic pain treated?

Standard treatment usually combines analgesic drugs with psychological (cognitive behavioural) therapies and rehabilitation treatments, physiotherapy or transcutaneous electrical neurostimulation, Alicia Alonso Cardaño, specialist in Anaesthesiology and coordinator of the SED Opioids working group, explains to SMC Spain Alicia Alonso Cardaño, specialist in Anaesthesiology and coordinator of the SED Opioids working group.

Generally, mild to moderate pain is treated with anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen or naproxen, and severe pain is usually treated with morphine derivatives (opioids) such as fentanyl or oxycodone, explains Alonso. The type of drugs prescribed not only varies according to the intensity, but also depends on the type of pain.

For example, when there is muscle spasm, muscle relaxants such as tizinidine are used; but if the pain is neuropathic, antiepileptic drugs such as gabapentin or antidepressants such as amitriptyline or duloxetine are usually used.

In addition, there are advanced therapies that are applied in the pain unit and require doctors specialised in anaesthesia, such as spinal blocks or deep brain neurostimulation.

Finally, there are some treatments in the research phase, such as virtual reality-based therapy, botulinum toxin and cannabis derivatives - which are already used in some countries - or gene and cell therapies that allow tissue regeneration, but their efficacy and safety have not yet been proven.

What are the risks of medication?

Many medications for the treatment of chronic pain have serious adverse effects. The best known case isopioid addiction. ‘For decades opioids have been prescribed for the treatment of chronic pain because it was recommended. Now, those patients find that they are addicted or dependent on opioids,’ reproaches Williams, who has worked with physical disability and addiction.

‘This was not clear when they were first prescribed,’ says the clinical psychologist, who now considers that opioids have few benefits and can worsen pain in the long term. In her opinion, it is important to offer alternative treatments and not to blame the patient for their dependence. ‘The process of tapering off opioids is very difficult and physically unpleasant,’ he acknowledges.

Addiction is not the only problem. Depression is very common in chronic pain patients. However, many drugs have adverse effects ranging from emotional instability or depression (gabapentin), to aggression, decreased libido (amitriptyline), insomnia or suicidal ideation (duloxetine).

‘The adjustment is complicated,’ Gobbo acknowledges. It requires a balance between symptom control, which will depend on the underlying illnesses, and the problems that may result from each drug, she explains.

Psychological pain or pain psychology?

The impact of the psychological and social aspects of pain has been recognised in medicine since 1977, when the biopsychosocial model was devised, which considers that everything is connected. In other words, it does not matter where the pain comes from, as it is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual, potential or described as such by the sufferer.

For this reason, in the classes he gives to doctors - organised by the Spanish Pain Society and other working groups in which he participates - Gobbo urges them to avoid terms such as ‘psychological pain’ or ‘psychogenic’. ‘Pain is pain, it is a perceptual experience and therefore all pain has a psychological implication,’ he insists.

‘The term “psychological” leads us to think that pain is not real,’ explains Serrat, who works in the Expert Unit on Central Sensitisation Syndromes of the Rheumatology Service of the Vall d'Hebron Hospital in Barcelona, and, at the same time, ‘to think that psychology can help to improve pain does not mean that pain is psychological,’ he clarifies.

In fact, the IASP specifies in its definition that pain does not necessarily have to be associated with physical damage, i.e. actual or potential tissue damage. It can be a mere replica of what it would feel like if there were such damage. But this information is not present in our culture, where pain is often understood as something purely physical and psychological pain is generally believed not to be pain, a mental illness or a mere exaggeration.

This encourages stigma and leads some professionals to reject treatments based on education, physical rehabilitation and psychology, which could significantly improve patients' quality of life, as the Ministry of Health's report on pain units acknowledges.

How does one learn to live with pain?

When there is a pervasive and permanent sensitisation to pain, it is normal to get caught in a frustrating loop. As Williams explains, sufferers long for complete pain relief, but this is rarely an option and often leads to false promises and expensive treatments. ‘They feel that the pain has robbed them of so much,’ she says. The alternative, says the psychologist, is to accept that the pain is ‘stuck in the system’ and manage the fear of movement.

‘It's about reversing the loop, conveying that you can move freely, that your activity is not going to cause harm,’ explained Arturo Goicoechea, who was head of the Neurology Service at the Hospital Santiago de Vitoria for more than three decades and is the author of the book El dolor crónico no es para siempre (Chronic pain is not forever ) (2023), in El País.

For example, in some injuries, such as back pain, it is better to return to a supervised and informed activity than to rest, but it is often thought that if there is pain, there is damage. This creates fear and causes the person to avoid movement. Over time, this rest generates more pain and can lead to other problems, such as fear of leaving home and social phobia, explained Almudena Mateos, a psychologist specialising in pain, at the conference organised by the SED Your Pain Matters 2024, held this October at the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos in Madrid.

‘Don't wait for the pain to go away to get back to your life, get back to your life and the pain will reduce or go away’, summarised Gobbo to patients who come to her practice with chronic pain. ‘It sounds easy,’ Williams points out, ’but it's not easy.