African elephants address each other with name-like calls, study finds African elephants address each other with name-like calls, study finds

Some animal species, such as parrots or dolphins, appear to address each other by imitating sounds from the receiver. However, animals addressing each other by individual names has only been observed in humans. Now, an international team of researchers says that African elephants can communicate through name-like calls and do not appear to rely on imitation to do so. According to the authors, who publish their results in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, the finding would imply that they have some degree of symbolic thinking.

Antonio Osuna - elefantes nombres EN

Antonio J. Osuna Mascaró

Postdoctoral researcher at the Messerli Research Institute at the University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna (Austria), animal cognition specialist

In my opinion, this is a fascinating study and another example of the recent advances in our understanding of communication in other species thanks to the use of machine learning.

We know very little about communication in other species and this (among other reasons) is because we are not sensitive to the many subtleties that the vocalisations of other species may contain. They are simply beyond our capabilities. This is why machine learning is proving so important: it allows us to highlight differences and similarities that we would otherwise never be able to distinguish.

In this case we have a surprising discovery that, despite being nearly 100 million years apart, elephants use something similar to the names by which we recognise ourselves in society. We already knew something like this in other deeply social species capable of vocal learning, such as dolphins and parrots, but elephants use these ‘names’ more closely to the way we do.

Dolphins use special ‘signature’ whistles and parrots use what are known as ‘contact calls’ (which to our ear often sound like a piercing cry). Both have similar functions to our names, but also important differences. Both dolphins and parrots repeat their own ‘name’ when communicating, and this becomes in a way their hallmark. Thus, when one individual wants to attract the attention of another, what they do is to imitate the ‘name’ that the other uses in their messages. So, yes, they have a similar function to our names, but they are also based on imitating the sounds of others.

In contrast, elephants seem to be doing something different and more like what we humans do. The vocalisations that elephants use to refer to another individual are not based on imitating the vocalisations of that other elephant; they are sounds that can be considered arbitrary. They refer to that individual and no one else, but they are inventions that, according to the authors, have a symbolic function similar to that of any of our human names.

The authors have been able to demonstrate that elephants attend and respond (either by vocalising, approaching or both) to these vocalisations referring to them and only to them. In addition, the analysis of these vocalisations has left some very interesting questions, as it is not entirely clear whether elephants in the same family call each member of the family by the same name, or whether each elephant may have several different ‘names’. It also remains to be known what other information these messages may contain, whether they may refer to individuals who are not present, and other interesting aspects such as the origin of these ‘names’. We have good clues to support their symbolic nature, but who invents them, and at what point in time do they do so? In dolphins and parrots the ‘names’ of each individual are modified sounds of those they use in their family, but here this does not seem to be the case.

In short, this is an extremely interesting discovery which, as it could not be otherwise in a field in which we still have so much to know, leaves more questions open than it answers, and that is fascinating.

Robert Barton - elefantes nombres EN

Robert Barton

Evolutionary biologist and Professor of Anthropology at Durham University (England)

Although the convergence on call structure for the same individual receivers from different callers is quite interesting, inferring ‘labels’ or even ‘names’ is fanciful and the data do not permit such inferences. Hence I’d question the author’s claim that “Evidence that arbitrary vocal labelling is not unique to humans would expand the breadth of models for the evolution of language and cognition.”

Their results might have nothing to do with language evolution. It isn’t too hard to imagine that animals learn, by associative learning, what sounds are associated with which individuals and that these could spread through socially-mediated reinforcement. This doesn’t mean that they are using a ‘label’ or a name in the sense that we humans would mean it, which is that it is a symbolic referent that ‘stands for’ the individual.

We see the same tendency to overinterpret data in those working on cetaceans and other ‘charismatic’ species. It would be nice to check whether you could get analogous findings in social insects, like bees, and then see if everyone agrees it is relevant to cognition and language evolution.

Miquel Llorente - elefantes nombres EN

Miquel Llorente

Head of the Department of Psychology at the University of Girona, associate professor Serra Húnter and principal investigator of the Comparative Minds research group

The study presented on African elephants and their ability to use specific calls to address other individuals sheds remarkable light on the complexity of communication in these animals, and offers significant implications for our understanding of the evolution of language and social behaviour. The results reveal that elephants can use specific, non-imitative sounds to refer to others, which is strikingly similar to human ‘names’. This finding suggests that the use of arbitrary vocal labels may be present in other species, challenging the idea that complex language is unique to humans. This discovery not only broadens our view of the evolutionary mechanisms of communication, but also raises fascinating questions about the similarities and differences in cognitive abilities between species.

Understanding how elephants and other animal species develop and use these vocal tags to communicate is crucial to deepening our understanding of the evolution of culture and social behaviour. This study fits well with existing evidence for sophisticated animal communication, but brings the novelty that these sounds are not mere imitations. The implications are significant, as this discovery could change our view of the evolutionary mechanisms of communication and language. If it is shown that elephants can transmit complex information in this way, we would be closer to understanding the roots of our own communication system. However, it is crucial to handle the interpretation of these sounds as ‘names’ with caution to avoid falling into an anthropomorphic interpretation of non-human phenomena.

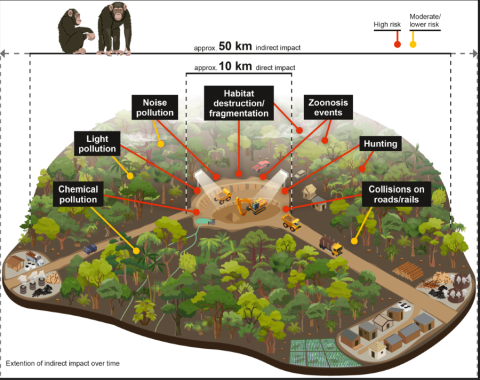

Furthermore, the threat of extinction facing African elephants underlines the importance of conserving these species not only for their intrinsic value, but also for their vital role in scientific research and our understanding of the natural world. The loss of these animals would also mean the loss of opportunities to better understand our own evolution and nature as biological and cultural beings. Ultimately, this study highlights the need to preserve biological diversity and promote the conservation of threatened species. Protecting these majestic animals is essential not only to maintain biodiversity, but also to continue advancing our understanding of animal and human behaviour.

Kurt Hammerschmidt - elefantes nombres EN

Kurt Hammerschmidt

Vocal Communication Specialist at the German Centre for Primate Studies in Göttingen (Germany)

I read the manuscript and must say that I found no evidence that African elephants address one another with individually specific name-like calls. However, the term “individually specific name-like calls” is self-contradictory. Names represent categories that apply to many individuals, they are not individually specific.

It is also interesting that this statement in the title is not repeated in the same way in the abstract. In the abstract the authors wrote: “Here we present evidence that wild African elephants address one another with individually specific calls, probably without relying on imitation of the receiver.”

And this is what the results really present. Some evidence that caller used a call variant similar to receiver call. That is imitation, less perfect like in dolphins and parrots, but there is no evidence of labels.

In addition, the statement being better than random is not really a good quality statement. In such communication studies a good assignment is at least 4 to 10fold higher than random (e.g. a study on adult female coo calls showed an individual assignment of these calls approx. 50 times above chance, 67 subjects, 68.5% correct assignment, chance level = 1.49%).

The characteristic of labels or names is their clear distinct nature, they have clearly distinguishable categories, like “a”, “b” or “c”, of in case of names, ”Joe”, “Mary”. The authors provide no evidence that such categories exist.

The playback study also showed no huge differences in the response to test and control calls. Figure 4 (right) shows that only 3 of the 17 elephants vocalized more. How a significance of 0.009 can emerge from this is a mystery to me.

Pardo et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Animals