A large study finds genetic variants associated with pregnancy loss

Around 15% of recognized pregnancies end in miscarriage, and it is estimated that almost half of all conceptions are lost in early stages, without people even realizing it. Now, a team from the United States and Denmark has analyzed data from more than 139,000 embryos from in vitro fertilization of nearly 23,000 couples and has found several genetic variants associated with a higher risk of miscarriage. Many of these are associated with meiosis, a key cell division process in sex cells. The authors, whose study is published in Nature, acknowledge that the new data will not allow for a precise estimation of individual risk, because the most important factors remain age and environmental elements.

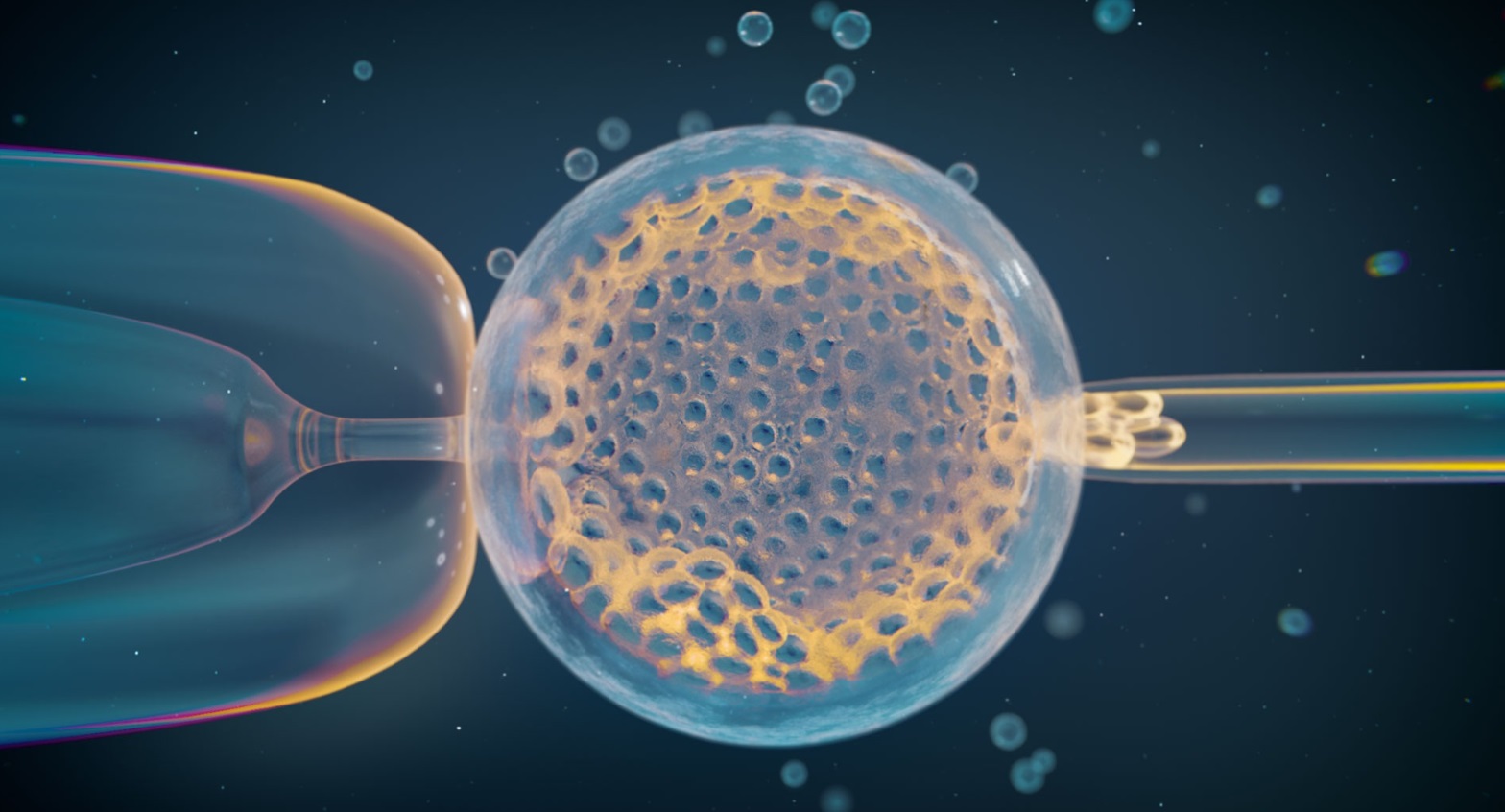

A routine IVF embryo biopsy for clinical genetic testing, which provided the large-scale genetic data analyzed in this study. Credit: Thom Leach, Amoeba Studios.

Calonge - Variantes

Rocío Núñez Calonge

Scientific Director of the UR International Group and Coordinator of the Ethics Group of the Spanish Fertility Society

Meiosis is the cell division process that occurs in eggs and sperm. Thanks to this mechanism, one cell with two copies of each chromosome gives rise to four cells with only one copy each. This process is essential for maintaining a constant number of chromosomes between generations and for generating genetic variability.

In women, meiosis begins before birth, during fetal development. At that time, the chromosomes pair up and exchange fragments of DNA in a process called recombination. However, meiosis stops and remains paused for years, until ovulation and, potentially, fertilization occur. During this long waiting period, problems can arise in the mechanisms that hold the chromosomes together. If this attachment fails, the chromosomes can separate prematurely, resulting in eggs with an incorrect number of chromosomes when meiosis resumes.

This incorrect chromosome segregation is one of the main causes of early pregnancy loss. It is estimated that around 15% of recognized pregnancies end in miscarriage, and many other conceptions are lost at very early stages without ever being detected. For years, it has been known that the most frequent cause is the presence of extra or missing chromosomes, a condition known as aneuploidy.

Despite this knowledge, it is still poorly understood how genetic differences between individuals influence these molecular processes. It is also unclear to what extent factors other than age, such as individual genetics, can predispose a woman to produce eggs with chromosomal abnormalities. To answer these questions, it is necessary to analyze the genetic information of a large number of embryos before pregnancy loss, as well as that of their parents.

In this context, the team led by Rajiv McCoy, a computational biologist at Johns Hopkins University, recently published a study in the journal Nature. The research was co-led by Sara Carioscia, a graduate student and first author of the paper, and Arjun Biddanda, a postdoctoral researcher.

The team analyzed data from embryos obtained through in vitro fertilization and compared the embryos' DNA with that of their biological parents. In total, they studied approximately 139,000 embryos from 23,000 couples. To manage this enormous amount of information, they developed a computer program that allowed them to identify relevant genetic patterns and associations.

Thanks to this large-scale analysis, the researchers were able to link certain maternal genetic variants to characteristics of chromosomal crossover and the risk of aneuploidy. The results revealed a shared genetic basis involving key genes in meiosis.

The study showed clear connections between specific variations in the mother's DNA and the likelihood that her embryos would not be viable. Unexpectedly, the same genetic variants associated with a higher risk of miscarriage were also linked to recombination, the process that generates genetic diversity in eggs and sperm.

The strongest associations were found in genes that control how chromosomes pair up, exchange genetic material, and remain attached during egg formation. Among these, the SMC1B gene stands out; it encodes a protein that is part of a ring-shaped structure that surrounds and holds chromosomes together. These structures are essential for proper chromosome segregation and tend to deteriorate with age.

Taken together, the results indicate that inherited genetic differences in these meiotic processes contribute to the natural variation in the risk of aneuploidy and miscarriage among individuals. This work provides the strongest evidence to date that common genetic variants can make some women more vulnerable to pregnancy loss.

However, the authors emphasize that, although genes related to miscarriage have been identified, it is still difficult to predict individual risk. This is because each common genetic variant usually has a very small effect compared to factors such as maternal age or environment. Even so, these genes represent promising targets for the development of future treatments.

Currently, the team is investigating rare genetic variants in both mothers and fathers that could have a more pronounced effect on the risk of aneuploidy. They are also using new technologies to better understand how subtle genetic changes can influence early pregnancy loss.

Taken together, these findings provide new insights into human reproduction and open potential avenues for developing treatments that reduce the risk of pregnancy loss. Furthermore, they deepen our understanding of the earliest stages of human development and lay the groundwork for future advances in reproductive genetics and fertility medicine.

Urries - Variantes

Antonio Urries

Director of the Assisted Reproduction Unit at the Quirónsalud Hospital in Zaragoza and member of the Quirónsalud Scientific Committee

This is a very high-quality study: one involving 139,416 embryos and 22,850 couples who underwent an in vitro fertilization cycle with genetic testing of their embryos represents a large sample size.

Furthermore, the statistical methods applied are appropriate, with results consistent with known biology from animal studies, thus reinforcing the conclusions.

Age has always been considered the main limiting factor in female fertility, given the increasingly advanced age at which women become pregnant. However, we often find women of similar ages who experience greater infertility problems and a higher risk of producing embryos with chromosomal abnormalities and of miscarriage for no apparent reason.

This study opens a new avenue of research, suggesting that very specific variations in the parents' DNA could be the cause of the more frequent generation of embryos with altered genetic makeup, as an independent and complementary factor to age.

Apparently, the problem could stem from a malfunction of the genes responsible for maintaining chromosome cohesion. These connections are essential for precise chromosome segregation and tend to break down as women age, which is linked to a higher risk of infertility and miscarriage.

This study suggests that the origin of this malfunction could be due to a decrease in the expression of genes such as SMC1B, C14orf39, CCNB1IP1, and RNF212, which would lead to fewer recombinations in eggs and thus increase the risk of aneuploidies. This has been suggested in previous studies in animal models, which indicated that "few recombinations" favor errors in the embryo's genetics, but never before demonstrated on this scale.

Although the individual risk of each variant is low and there is no direct intervention, it can change practice, especially in research, by helping us prioritize genes and pathways for functional studies, improve aneuploidy risk models, and leverage PGT [preimplantation genetic testing] data as a great platform for studying human meiosis.

[Regarding possible limitations] It should be noted that the study is based on couples from in vitro fertilization cycles, not the general population, with the population bias that this implies.

Furthermore, the heritability explained by common variants is low, and the study does not adequately analyze rare or structural variants or environmental factors. Therefore, at this time, it is not useful for making a systematic, individual clinical prediction, although it helps to better understand the mechanisms of meiosis.

Vassena . Variantes

Rita Vassena

Medical Director of Fertility at CooperSurgical

This paper by Carioscia and colleagues focuses on the study of embryonic aneuploidy, i.e. embryos with an abnormal number of chromosomes, which is estimated to be the reason why up to half of all human conceptions fail to develop to term.

While it is well established that aneuploidy is related to the crossover between homologous chromosomes during the first meiotic division, which occurs when the eggs are still in the ovary, this study deepens our understanding of the relationship between DNA variations and aneuploidy.

In this very extensive and well conducted study, the authors sequenced the DNA of 139.416 embryos which were generated by 22.850 couples during their fertility treatment. The DNA of embryos is often analyzed during in vitro fertilization treatments, and this study has deepened the analysis of the same material further.

By looking at the naturally occurring variations in DNA sequence in both embryos and parents, the authors have been able to link specific inherited DNA sequences with the likelihood of an embryo to be aneuploid. In doing so, they have uncovered the relationship between sequence variants and genes involved in DNA recombination and occurrence of aneuploidy to a level of detail previously not achieved.

While their discoveries do not yet offer practical solutions for IVF patients, this work constitutes an important contribution to our understanding of the biology of aneuploidy and of human development.

Conflict of interest: "The company CooperSurgical, my employer, also sells, among other things, genetic analysis services for embryos, although this is not the service used in this article."

Trilla - Variantes Aborto

Cristina Trilla Solà

Director of the Prenatal Screening Unit and attending physician in the Obstetrics service of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (Barcelona)

Overall, I find the article to be of high quality, both in terms of design and the study's scope in terms of sample size and analytical rigor. It is an ambitious, well-planned, and well-executed work that addresses a central question in human reproduction: why meiotic errors and aneuploidies occur, which are responsible for 50-60% of pregnancy losses. The authors conclude that these can be partly explained by maternal genetic factors that go beyond age.

Strengths include:

The sample size, clearly. It provides significant statistical power.

- A specific computational method has been developed to relate crossovers and aneuploidies by tracing parental haplotypes.

- The main results appear biologically consistent, given that the genes in which they identify common variants (especially SMC1B) are associated with recombination and aneuploidy due to alterations in maternal meiosis.

- In summary, this is a suitable approach with a solid methodology and consistent results that would allow for establishing a link between advanced genetics and human embryology beyond the classical concepts of aneuploidy and maternal age.

The article confirms several previous findings. Above all, that aneuploidy is related to maternal age, primarily due to maternal meiotic origin. It was also known that insufficient or malpositioned crossovers have a higher risk of meiotic nondisjunction and, therefore, aneuploidy (although I believe there was some controversy here due to inconsistent findings among some studies). The results of this study tell us that embryos with aneuploidy tend to have fewer crossovers in disomic chromosomes, which would therefore be a global indicator of 'less efficient meiosis'.

Beyond this, the main contribution lies in the identification of alterations in specific genes involved in meiosis. However, I believe the clinical impact of this is currently limited, as it doesn't appear to be actionable at present, and furthermore, the causal contribution of these findings (individual risk of each variant) is very low. It might perhaps help to slightly better predict a woman's individual risk of having a meiotic abnormality, although maternal age would still remain the greatest contributor to aneuploidy risk.

On the other hand, in the current social context and reproductive landscape, these results reinforce the concept that there may be an individual susceptibility to aneuploidy beyond maternal age. In my opinion, this could be particularly helpful in interpreting some cases where we find higher-than-expected aneuploidy rates, especially in young women. It could also help guide translational research toward more specific diagnostic targets (precision medicine), which is often lacking in the context of reproductive medicine. And finally, it could open the door to more advanced reproductive genetics, although in my opinion this is still far from having clinical applicability. There's been a lot of talk lately about polygenic scores; this could be one avenue, especially if rare variants with greater impact could be identified.

Despite all of the above, and it's important to keep this in mind, and although I think it's a good article, there are inherent limitations in the design. First, it was conducted in a very specific population (infertile women undergoing IVF with PGT-A [Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidies]). The authors don't report the IVF indication in much detail, as far as I can understand, and therefore, they don't represent the entire fertile population, nor even the subgroup of women with miscarriage or recurrent miscarriage. This does not diminish the value of the findings, given that they are likely to have long-term clinical implications in the context of assisted reproduction, but it is a limitation when generalizing the data to women or couples with spontaneous abortion, and even more so outside the context of assisted reproductive techniques.

On the other hand, it's important to remember that PGT-A involves a trophectoderm biopsy, which represents approximately six cells in a blastocyst that, logically, contains many more. Therefore, there is a risk of mosaicism, and furthermore, these cells actually represent what occurs in the placenta, not in the embryo (inner cell mass). So, again, caution is necessary. We also know that embryos have the capacity for 'repair,' and there are reported births of healthy (and euploid) children after transfers of embryos with aneuploid or mosaic PGT-A. This study focuses primarily on mechanisms that allow us to better understand aneuploidy, but we cannot conclude that this necessarily translates into pregnancy failure (although we logically know there is a relationship, it is not the focus of the study).

Finally, one detail that I consider essential: this article did not actually analyze cells obtained from spontaneous abortions or abortions following assisted reproductive technology. And yet, they extrapolate the data to the risk of miscarriage. These are results of aneuploidy detected by PGT-A prior to transfer, so they are not actually applicable to spontaneous abortion. Many of these embryos, if transferred, would not even implant, so they would not result in a miscarriage as such.

It makes sense that the authors refer to miscarriage, given that 50-60% of spontaneous abortions are due to chromosomal rearrangements, which is true. However, it should also be noted that this percentage decreases with a greater number of previous miscarriages. In other words, the more miscarriages, the lower the probability that they are due to genetic causes (this has been confirmed in previous articles). This implies that, in women with recurrent miscarriage, the mechanisms involved in pregnancy loss are not so much related to aneuploidy, but rather to metabolic disorders, uterine malformations, chronic inflammation, or thrombotic events, among others. This seems very relevant to me when considering the clinical application of these results, given that we see the impact is even more limited.

Therefore, I believe we must be cautious when interpreting these results and avoid conclusions such as the discovery of ‘a gene that predisposes to miscarriage,’ that ‘miscarriage is hereditary,’ or that miscarriage could be prevented with a genetic test. What I conclude from this study is that part of the risk of pregnancy loss due to aneuploidy could have a polygenic, small-effect, and multifactorial genetic component, and that this is a good piece of work that helps us understand the mechanisms of aneuploidy in infertile populations (the title of the article is ambitious because it implies that they have discovered the cause of aneuploidy, although the actual clinical contribution of the findings is limited, but at least it is correct in the sense that it is limited to talking about aneuploidy, without extrapolating to miscarriage).

Carioscia et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Non-randomized

- People