The United Nations, like any good thriller, has accustomed us to unpredictable (and sometimes heart-stopping) endings in which we can only guess the outcome at the very end of the story. We have seen it at every annual COP on climate change (this year it will be COP27 and we are still counting COPs) and we have seen it again at the last Intergovernmental Conference (IGC-5) for the "Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biodiversity in Waters Beyond National Jurisdiction", i.e. the so-called "Oceans Treaty" or BBNJ Treaty (Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction). This conference was suspended a few days ago without reaching a final agreement.

This slow multilateral negotiation mechanism - which climate activist Greta Thunberg called "blablablablah" - is justified by states as a need for consensus, but it is important to remember that the climate of future generations or the health of the oceans is at stake in these negotiations. And with each delay without reaching solutions, global problems get worse.

With each delay without solutions, the global problems get worse

Discussions on the possible BBNJ Treaty began at the United Nations in 2006 and formal negotiations were launched in 2015 with a Preparatory Committee (PrepCom) and the subsequent Intergovernmental Conference or IGC. The Treaty was to be concluded in a maximum of 4 sessions (IGC-1 to IGC-4). IGC-5 represents a grace session, as in university exams, and had to be stopped, not concluded, due to the impossibility of reaching an agreement.

After a process lasting more than 16 years, only half a session separates us from the word failure, a word that today fills the headlines of all the international newspapers. Let us hope, however, and I hope, that the resumption of the last session, possibly in the spring of 2023, will give us the Treaty that we all want. A Treaty that was pre-baptised by UN Secretary General António Guterres as "the Paris Oceans Agreement", an indication of its great importance.

The elements of negotiation

The future treaty for international waters consists of four main elements:

- Marine genetic resources, including the sharing among all states of their potential benefits.

- Spatial management tools such as major international Marine Protected Areas.

- Environmental impact assessments in international waters.

- Capacity building for developing countries, including the transfer of marine technology from more developed countries.

Environmental impact assessments are a particularly important element because there is currently no global competent authority for their implementation and monitoring. Many activities in international waters are not required to carry out EIAs, and those that do differ in their requirements and implementation. The new treaty will provide consistency and legal certainty, establish safeguards for marine ecosystems, initiate best practices and consider cumulative impacts. Disagreements at the last conference (IGC-5) have centred on the thresholds required for these assessments to be initiated, or on the power or decision-making capacity of the future Conference of the Parties (COP) that will manage the implementation of the Treaty.

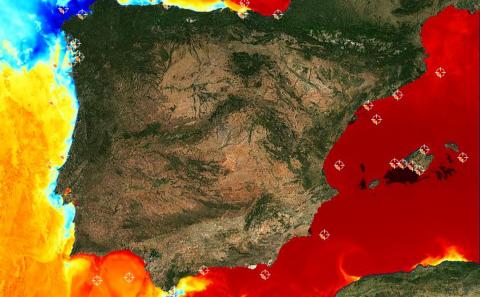

States' perspectives also vary in relation to so-called spatial management tools, which aim to conserve and sustainably use areas in need of protection, including most importantly the creation of a global network of connected Marine Protected Areas representative of major ecosystems. The Treaty is fundamental for these Marine Protected Areas to cover 30% of the global ocean by 2030 (the so-called 30x30 target), which will effectively protect marine biodiversity.

The Treaty is essential for Marine Protected Areas to cover 30% of the global ocean by 2030

The Treaty is essential for Marine Protected Areas to cover 30% of the global ocean by 2030.

It has been estimated that virtually all Marine Protected Areas, for example in the Northeast Atlantic, will be impacted by climate change in the coming decades. A key consideration for the future Treaty will therefore be to ensure that Marine Protected Areas and other spatial management tools can adapt to spatio-temporal changes in the species, ecosystems and habitats we seek to conserve now and in the future.

Marine genetic resources, the first element of the Treaty, remains the biggest obstacle to consensus at the Conference, especially with regard to the sharing of monetary benefits from their commercialisation. This is sadly indicative of the greater weight of economic considerations over environmental ones in international negotiations.

Other disagreements include the retroactivity of the Treaty, and the terminology surrounding access to marine genetic resources and their derivatives (proteins, DNA), which may be accessible not only in situ but also from bio-repositories (ex situ access), genetic databases (in silico access) and cell cultures (in vitro access). The technicality of definitions and regulations for access and utilisation of these resources are key issues in the negotiation, especially for developing countries that have difficulties in carrying out this type of research.

The need for a more effective system

A treaty obtained by consensus of the 168 participating states is a robust agreement, but this methodology has limitations, as the unborn BBNJ Treaty has shown. Negotiations are prolonged excessively over time while the problems they seek to solve increase; any State has the capacity to block or delay the agreement for reasons other than the general interest; and to obtain a final consensus it may be necessary to lower the objectives to such a level that their implementation is not effective for the problems they seek to solve, as we have seen in the negotiations on climate change. Perhaps we should equip ourselves with a methodology better suited to the challenges of our time.

Having said that, I would like to stress that the last session of the Oceans Treaty (IGC-5) is the closest we have come to reaching consensus and to remember, as Richard Feynman taught us, that if we focus only on the failures we will continue to suffer, while if we focus on the lessons, we will continue to grow.