Reaction: Chinese researchers successfully clone a rhesus monkey

A team of Chinese researchers report today in the journal Nature Communications the successful cloning of a rhesus monkey, with a healthy placenta, which survived for more than two years. According to the authors, this could improve the efficiency of the monkey cloning process, which so far is very low. Previously, different teams have cloned more mammalian species, including 'Dolly the sheep' and another species of macaque (Macaca fascicularis).

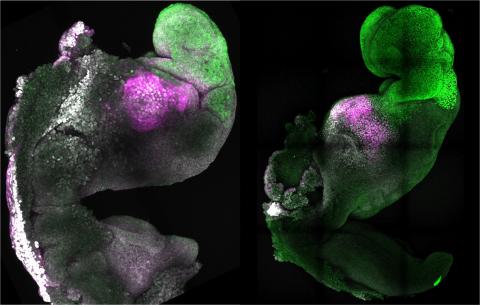

Photograph of the somatic cell-cloned rhesus monkey produced through trophoblast replacement, taken at 17 months. Credit: Zhaodi Liao et al., Nature Communications.

Lluís Montoliu - mono clonado EN

Lluís Montoliu

Research professor at the National Biotechnology Centre (CNB-CSIC) and at the CIBERER-ISCIII

On July 5, 1996, at the Roslin Institute near Edinburgh, the sheep Dolly was born, the first cloned animal from adult cells. However, the world wouldn't know about it until February 1997 when this biological feat was reported in a historic and controversial article in the journal Nature, sparking the imagination and fears of half of humanity. If it was possible to clone sheep, why wouldn't it be possible to clone humans?

In reality, those fears were entirely unfounded. Cloning other mammal species became a slow drip that demonstrated the intrinsic difficulties of each species, with distinct characteristics in their reproductive biology necessary to adapt the original method developed to clone Dolly the sheep. Cows and mice were cloned in 1998, goats in 1999, pigs in 2000, cats and rabbits in 2002, rats and horses in 2003, and dogs in 2005.

And what about primates? If the original fear was human cloning, it should be possible to clone other primate species first. The truth is that the first successful cloning of primates didn't happen until February 2018, exactly 21 years after Dolly's birth. A team of Chinese researchers, led by Qiang Sun from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai, described the cloning of crab-eating macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in the journal Cell. The significance of that article was the efficiency of the process, around 1.5%, surprisingly low and not far from what was obtained in the original cloning of Dolly and in most cloned species, once again emphasizing the technical difficulties of the somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) process, which is the appropriate term for cloning. This poor efficiency confirmed the obvious: not only was human cloning unnecessary and debatable, but if attempted, it would be extraordinarily difficult and ethically unjustifiable.

Now, almost six years later, the same team of Chinese researchers, again led by Qiang Sun along with Zhen Liu, reports in the journal Nature Communications the cloning of another primate species, the Rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta), after multiple previous failed attempts. Success was achieved by combining the treatment of cloned embryos with Trichostatin A (a histone deacetylase inhibitor) and Kdm4d (a histone demethylase), both already used in the previous cloning of crab-eating macaques and aimed at altering the epigenetic state of cloned embryos, with a sophisticated method of trophoblast replacement, the cells surrounding the inner cellular mass in the blastocyst that will later give rise to the placenta. Again, the efficiency of the process is similar, even lower: one surviving cloned animal out of 113 initial embryos, less than 1%.

Both the cloning of crab-eating macaques and Rhesus monkeys demonstrate two things. First, it is possible to clone primates. And second, no less important, it is extremely difficult to succeed with these experiments, with such low efficiencies, once again ruling out human cloning. The authors suggest that this technique should complement the use of both primate species in biomedical research. As a derivative of their new cloning method, they mention that trophoblast replacement could have potential as a new assisted reproduction technique in cases where human embryos show deficiencies in trophoblast development.

Finally, it is worth noting that these experiments could not have been conducted in Europe, as the European Union's legislation on animal experimentation prohibits the use of non-human primates unless the experiment is aimed at investigating a serious, life-threatening disease affecting humans or the primate species itself, which is not the case in this experiment.

Liao et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Animals