Reactions: specific antibodies found in blood samples from patients years before they develop multiple sclerosis

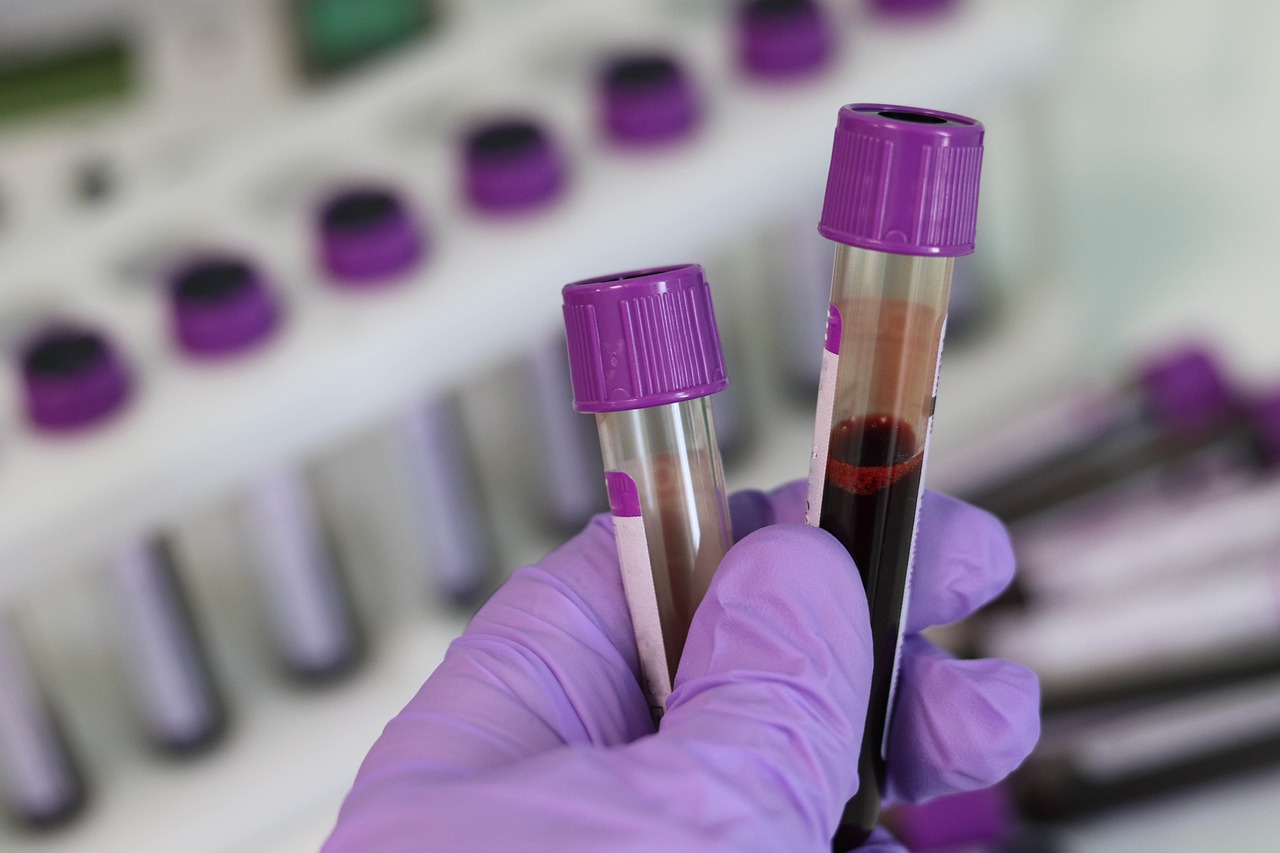

Researchers have found specific antibodies in the blood of patients years before they showed symptoms of multiple sclerosis. This group of antibodies was present in 10% of the 250 people who later developed the disease, and were part of a sample of over 10 million US military personnel. The finding could have potential for early detection of multiple sclerosis, says the research team in a paper published in Nature Medicine.

EM signature - Enric Monreal EN

Enric Monreal

Neurologist at the CSUR Multiple Sclerosis Unit of the Ramón y Cajal University Hospital and member of the Ramón y Cajal Institute for Health Research

The causes of multiple sclerosis (MS), an autoimmune disease and the second leading cause of disability in young people, are not fully understood. However, a genetic predisposition is acknowledged, and environmental factors have an impact on that predisposition. Some viral infections stand out amongst those factors, like the one caused by the Epstein-Barr virus.

This study, published in a world-renowned journal (Nature Medicine), attempts to delve deeper into the processes involved in the years prior to the onset of symptoms in MS. It uses the same database of US military service patients (10 million) that was used in another study. This study was published in 2022 in the prestigious journal Science, and sought to deepen the relationship between the Epstein-Barr virus (responsible for the mononucleosis infection, also known as "the kissing disease") and MS.

In this case, they collect samples from patients who subsequently develop MS (250 in total) for whom serum samples were available from about five years before and one year after the diagnosis. They are compared with a cohort of 250 other healthy individuals to analyse the spectrum of auto-antibodies (antibodies erroneously directed against self-structures) generated by the immune system before diagnosis, as well as their relationship to neuronal damage (measured by the light chain of neurofilaments in serum). In about 10% of MS patients, a different auto-antibody profile is observed, some of which may be cross-reactive with some pathogens (such as Epstein-Barr virus itself). This would indicate that the infection develops specific antibodies against the pathogen and, subsequently, these antibodies attack their own structures due to molecular similarity.

The main use they see for these results is to use these autoantibodies to detect a possible MS in patients with a high risk of developing this pathology (e.g., relatives of patients). However, in the near future, there isn’t a clear prospect that these autoantibodies could be measured in clinical practice in the short or long term.

Overall, the study is high quality, as required in a journal of this category. In addition, the findings are confirmed in an independent cohort, which makes the results more robust. However, the group they studied is small, which could introduce an understimation of associtation type of bias.

EM signatura - Luis Querol EN

Luis Querol

Neurologist in the Neuromuscular Diseases Unit - Autoimmune Neurology - Neuromuscular Lab

Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau & Institut de Recerca Biomèdica Sant Pau, Barcelona

Multiple sclerosis is a disease in which B lymphocytes are key. B-lymphocytes, when mature, become cells that produce antibodies. When these lymphocytes react against our own antigens (their molecular target), an autoimmune disease develops, such as MS.

Autoantibodies have been described in many other diseases in which B-lymphocytes are key. These allow us, not only to better understand how the disease develops, but to also diagnose the diseases more accurately –since each autoimmune disease has autoantibodies that are specific to that disease, which can be measured in blood or cerebrospinal fluid–. Multiple sclerosis has always been an exception to this rule. Despite being a disease in which B-lymphocytes are crucial, no autoantibody has ever been found to explain the disease or to allow earlier diagnosis, despite persistent searches using multiple types of techniques. Some antibodies have been found that seem to be present in small groups of patients. This study is along the same line, but using a novel technique (phage immunoprecipitation) for mass detection of autoantibodies.

The study has several implications for understanding the disease and for further research, although, I believe, these are not currently implementable in clinical practice. The first implication is that it seems clear that not all patients are immunologically the same. This is something we already sensed for other reasons, but the study reiterates it. Probably, what this means is that, from a mechanism and causes the point of view, MS is not one disease, but a collection of diseases that manifest in a similar way but have different mechanisms. The other important, and known, implication, is that there may be external pathogens (Epstein-Barr virus in particular) that, although they are not the only cause, they may play a triggering role in a predisposed population.

The most important limitation is that in the vast majority of diseases in which B-lymphocytes are important, autoantibodies recognise molecules on the membranes (surface) of cells (because antibodies do not easily enter the cell), and those molecular targets have a complex three-dimensional conformation. But the antibody detection technique that was used in the study recognizes pieces of proteins (not complete proteins) that do not have the natural conformation and do not necessarily belong to membrane proteins; so, repeating the study with a technology that detects autoantibodies directed against complete proteins and, if possible, membrane proteins, would perhaps be a better approach.

To summarize, this is an interesting study that uses a novel technique to detect a population of MS patients who share immunological mechanisms, but it is also a study in which some technical aspects, the low frecuency in which the autoantibodies were found and the complexity of the technique used, prevent us from defending this technique as something that can be used in clinical care at the present time.

EM signature - Manuel Comabella EN

Manuel Comabella López

Director of the Clinical Neuroimmunology Laboratory at the Multiple Sclerosis Centre of Catalonia (Cemcat) and neurologist at the Vall d'Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona

This is a study conducted by researchers at the University of California (San Francisco, USA) on blood samples from active-duty US military personnel. They identified 250 individuals who later developed multiple sclerosis (MS) and had a blood sample available several years before the first symptoms appeared and one year after the disease was diagnosed. They also identified a control group of 250 individuals with similar demographic characteristics who did not develop MS.

In a subgroup of 10% of the individuals who develop MS, they found a specific pattern of antibodies in the blood directed against several of the body's own proteins, which is not present in the remaining individuals who develop the disease, nor in the control group, and this pattern appears stable over time. In addition, individuals with this pattern had a higher concentration of light-chain neurofilaments in their blood, a protein that indicates damage to neurons.

Access to samples from individuals before the development of a disease is of paramount importance for studying the biological factors that operate or influence the early stages of complex diseases such as multiple sclerosis, in which there is an interplay between genetic and environmental factors. The study is also important because it unravels the high heterogeneity inherent in multiple sclerosis and identifies a subgroup of patients characterised by an antibody response to the body's own proteins - different from that of other patients with the disease and different from healthy individuals - that may help in earlier diagnosis of these patients. Although not demonstrated in the study, perhaps these patients will also have a worse prognosis for their disease, based on the higher concentrations of neurofilaments found in their blood, and will require more aggressive treatment for their disease.

EM signature - Ana Belén EN

Ana Belén Caminero

Coordinator of the GEEMENIR group (Study Group on Multiple Sclerosis and Related Neuroimmunological Diseases ) of the Spanish Society of Neurology and head of the Neurology Section of the Ávila Health Care Complex

This study is the result of research conducted over many years by a group of researchers at the University of San Francisco in California (UCSF) and the Chan Zuckerberg Biotechnology Research Center (Biohub) in the same city. The initial purpose was to discover causative agents of multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic neurological disease affecting the central nervous system (CNS, which includes the brain, spinal cord and optic nerves) that it is presumed to be immune-mediated (autoimmune). MS causes demyelination and axonal damage, resulting in a wide variety of symptoms.

To do this, they used a complex biological technology ('phage expression libraries') that allowed them to study more than 10,000 proteins present in the human body, to detect which of the antibodies present in the blood of these people with MS -or groups of antibodies- were the ones damaging or attacking structures in their CNS and producing the disease. — Thus behaving as autoantibodies. —

One of the main strengths of this study is that the blood/serum samples from these subjects came from the US department of defence serum repository, which stores samples from more than 10 million US military personnel. Of these, 250 subjects subsequently developed MS over the years. And what could be seen is that 10 % of these people with MS had and shared a specific set or group of antibodies in their blood, already years before they developed the disease. These antibodies, moreover, were very similar to those that develop in the course of infections caused by micro-organisms that very frequently affect humans, including the Epstein Barr virus (EBV), which has been linked in many previous studies to MS.

It is again clear from this study that the immune system of people with MS mistakes the proteins of this virus for those of their own CNS and attacks them, leading to the symptoms of the disease. This is because EBV - and possibly other viruses as well - contain protein sequences similar to some proteins present in the CNS.

For these kinds of conclusions, it is not possible to conduct randomised studies (which are the highest level of evidence of health outcomes possible), so what are known as 'natural experiments' - longitudinal studies of incident cases of MS - are conducted. Moreover, these data were confirmed in another cohort of patients and there is biological plausibility that they are credible. It was also possible to rule out reverse causality (in this case, it was deemed highly unlikely that it was the MS what predisposes individuals with MS to have an EBV infection).

This study fits well with the results of previous studies. Firstly, there is a pre-symptomatic or preclinical period of the disease that lasts several years. During this phase, the patient does not have yet the typical symptoms of MS, but has other non-specific, prodromal, symptoms, in which an inflammatory process within the CNS may already be developing. However, very few patients are diagnosed with the disease at these stages. On the other hand, it helps to consolidate the importance of EBV in the development of MS. Two years ago, another important study was published -also in the same cohort of US servicemen-, that showed a MS risk increase of 32-fold after EBV infection, but not after an infection of other viruses that are transmitted in a similar way, such as cytomegalovirus. It is currently the most important and well-established risk factor.

The most important consequence of all this is that, by studying this immunological fingerprint, it might be possible to identify subjects at risk of developing MS in the coming years and, thus, start disease-modifying treatments as early as possible and implement all the measures aimed at preventing the accumulation of disability. On the other hand, and preventively, the development of an effective vaccine against EBV could potentially prevent this disease if applied before the subject has been infected by the virus. In addition, the results of this research open new paths to improve health outcomes for MS patients.

Colin R. Zamecnik et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- People