Reactions to research warning of risk of more viral zoonoses due to climate change

Climate change will lead to at least 15,000 new cross-species virus transmissions by 2070, as habitat shifts on a 2°C warmer planet will bring previously distant animals closer together. This result, published in Nature, points to increased exposure of humans to pathogens from wild animals.

Downloadable high-resolution infographics.

Ignacio González Bravo - transmisión virus entre especies - EN

Ignacio González Bravo

Research director at the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases and Vectors: Ecology, Genetics, Evolution and Control (MIVEGEC) of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS).

The team led by Dr Shweta Bansal has analysed the projected evolution of zoonosis risk from the present to 2070 under different scenarios of climate change, land-use change (from forest or jungle to crops, for example) and mammal migration.

The results show that the changes will lead to a large number of new contacts between animal species that have never shared habitats before. This cohabitation will make it possible for viruses infecting one species to gain access to a new host species and successfully jump species. The researchers predict that the hotspots for these new contacts are in the ecologically rich high-altitude regions of Asia and Africa. The researchers also show that bats are likely to be involved in the vast majority of new contacts between mammalian species.

For humans, the researchers show that the centres of new contacts and possible zoonoses until 2070 are centred in tropical areas with high population densities and geographical variations in altitude, such as the Sahel, the plateaus in Ethiopia, the Rift Valley, India, eastern China, Indonesia or the Philippines.

The results suggest that many of these habitat changes are already underway, so that the potential for new interspecies contacts and the likelihood of zoonoses will increase in the coming decades.

Dr Shweta Bansal's team's projections can only include the virus-host relationships we know about, of course. For many poorly known viruses that are potentially dangerous to humans, such as the Usutu virus, or for viruses for which we do not know the source and host in the wild (such as the Zaire Ebola virus), accurate forecasts cannot be made. Likewise, we do not yet fully understand why some species jumpers are successful and can lead to pandemics (such as HIV or SARS-CoV-2) and eventually become endemic (such as other human coronaviruses), while many others are unable to establish in the new species and are fortunately restricted to epidemic outbreaks. So we cannot yet predict how many of these new contacts and possible zoonoses will lead to local or global health emergencies.

The positive side of this work is that it identifies potential foci of new contacts between mammalian species. In this way, epidemiological surveillance can focus on potential high-risk species, in areas of high human density and land-use boundaries.

José Antonio Oteo Revuelta - transmisión virus entre especies - EN

José Antonio Oteo Revuelta

Head of the Department of Infectious Diseases. Director of the Laboratory of Special Pathogens. Center for Rickettiosis and Diseases Transmitted by Arthropod Vectors. San Pedro University Hospital - CIBIR (La Rioja)

The appearance of a specific emerging infection is conditioned by multiple factors, among which population movements and global warming undoubtedly play a very important role. For years, work has been carried out on predictive models that help to take measures to reduce the impact of micro-organisms with the potential to cause disease in humans and/or other animals. In fact, we are currently experiencing the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, and the pandemic potential of SARS-CoV has been warned for years.

The surveillance of micro-organisms present in the animal world and its arthropods (which is where the threats come from, analysed in conjunction with other factors), and their computational analysis allows the prediction of possible interactions between these and different animal species. We know that there are thousands of viruses in their animal reservoirs that have not yet interacted or, if they have, have not been able to adapt to their new host. This work by Colin Carlson's group at Georgetown University (Washington, DC, USA) estimates that by 2070, and in close relation to global warming, there will be at least 15,000 virus crosses with other species. This means that these viruses will be able to adapt and spillover will occur. Depending on the type of virus, it can then be transmitted from person to person or simply cause damage to that host, or small outbreaks. In the article they study the possibility of thousands of interactions between viruses and animal species in a 2ºC global warming scenario.

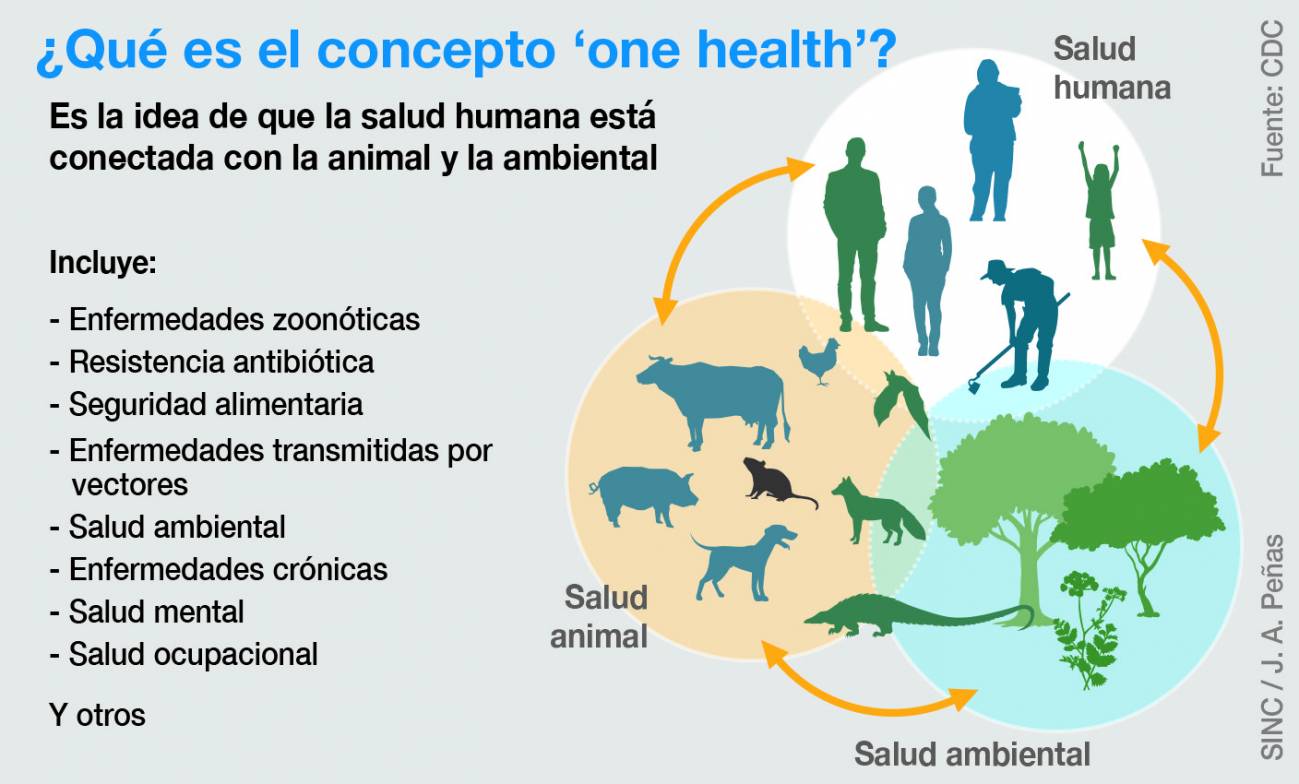

It is well worth a read and especially worth raising awareness of the major problems arising from global warming. Only a "One Health" approach in which we take care of all aspects involved in the emergence and re-emergence of new infections can mitigate our uncertain future.