The survival of mammalian species like humans depends on the preservation of immature egg reserves (oocytes) for years; decades in the case of women. How these cells achieve such remarkable longevity was not clear, but a study published this week in the journal Cell and led by the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona sheds light on this phenomenon.

"The problem faced by long-lived cells is the aggregation of proteins," explained CRG researcher and co-author of the study Gabriele Zaffagnini during a briefing organized by the Science Media Centre Spain. These aggregates are toxic, but oocytes have a hard time getting rid of them: they cannot do so through cell division, a precious commodity in their case. Nor can they actively eliminate them, which would entail a huge energy expenditure over the years.

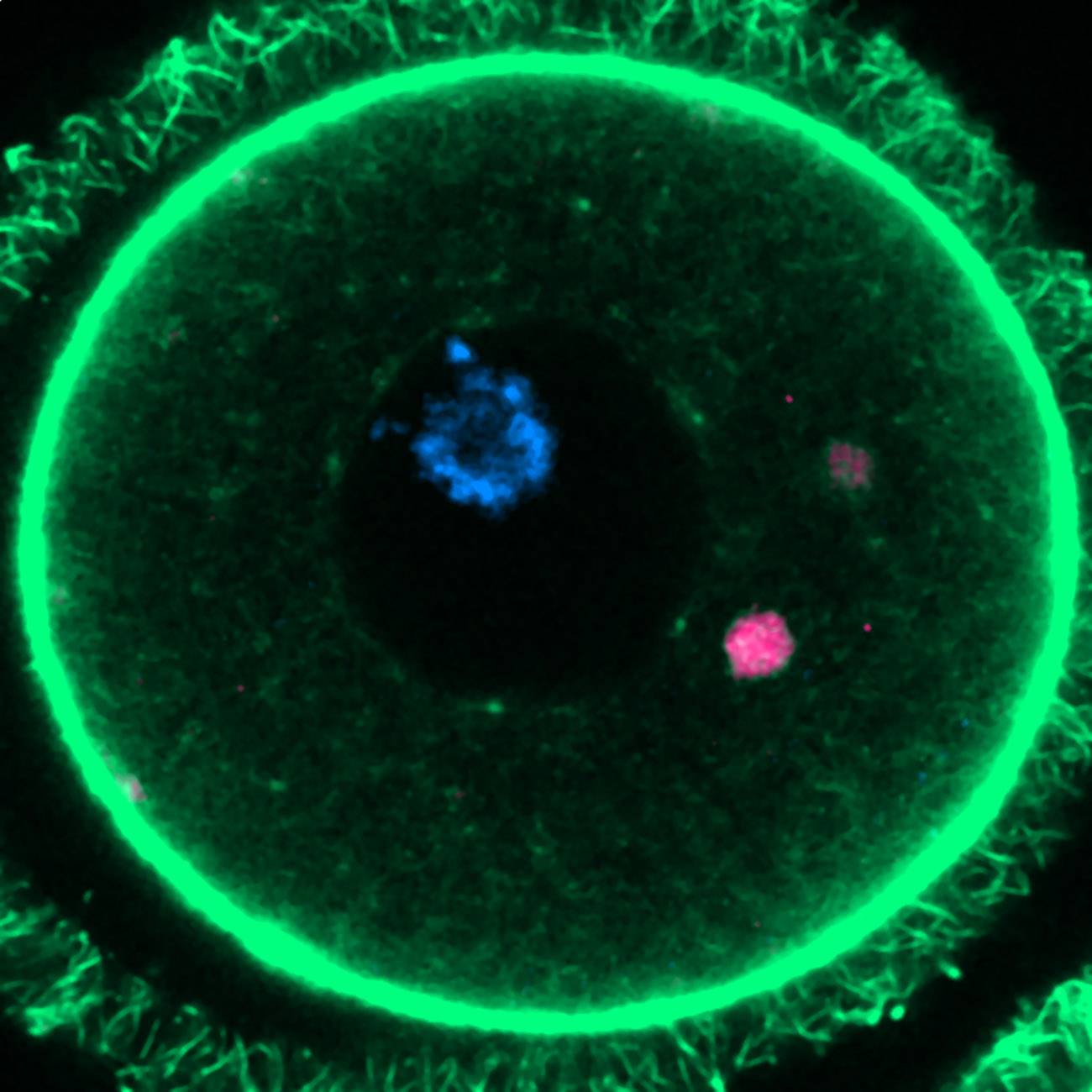

The solution for oocytes lies, according to Zaffagnini, in accumulating these harmful aggregates in large structures dubbed ELVA (Endo-Lysosomal Vesicular Assemblies). "They are organelle clusters with properties that individual lysosomal vesicles do not have," he commented. Thus, they can merge with each other to 'park the garbage' of the oocyte and temporarily forget about it.

This research opens an interesting avenue for future study to explore whether protein degradation and its dysregulation could explain the deterioration of oocyte quality associated with age

Rocío Núñez Calonge

"In immature eggs [the ELVA] are inactive, and we believe that this is a form of energy saving because, since the egg has to survive for a long time, constantly degrading [the toxic protein aggregates] would have a great cost," clarified Zaffagnini. Once the egg matures and prepares for ovulation, the "superorganelles" are activated and do degrade the aggregates they contained because an embryo "cannot survive if it inherits them."

Zaffagnini's study was conducted with mice, but the researcher stated that the next step is to analyze the presence of these ELVA in human eggs and see if their faulty regulation could be a factor in the age-related loss of fertility. "This research opens an interesting avenue for future study to explore whether protein degradation and its dysregulation could explain the deterioration of oocyte quality associated with age," commented Rocío Núñez Calonge, the scientific director of the International UR Group, in a reaction reported by SMC Spain.

Antonio Urries, director of the Assisted Reproduction Unit at Quirónsalud Hospital in Zaragoza, highlights: "From a reproductive point of view, this article is very interesting as it shows how the presence of certain protein aggregates in the cytoplasm of eggs can lead to poor oocyte quality and embryos with a low probability of becoming pregnant, even if they have the correct genetic load".