What are cancer vaccines?

They are a form of immunotherapy that stimulates and 'educates' our defences to target a tumour. They work in some ways similarly to traditional vaccines against micro-organisms such as viruses and bacteria: the aim of both is to make the immune system recognise parts of the target to be eliminated - the so-called antigens - and become more active and effective in fighting it.

A fundamental difference, however, is that micro-organisms are foreign agents, whereas tumours arise from the cells themselves. This complicates the design of cancer vaccines, as it is easier to direct defences against something that is nothing like what they are used to.

In the middle ground between them are vaccines against viruses capable of causing tumours, such as human papillomavirus (HPV) or hepatitis B virus. When we refer to cancer vaccines, we usually refer to vaccines that directly target the tumour.

Are they preventive or therapeutic?

While vaccines against micro-organisms are primarily preventive (they work by preventing infection or making it less severe if it does occur), most cancer vaccine trials are done to treat a tumour that has already developed. Although there are also studies with preventive vaccines, these are rarer and face more difficulties: on the one hand, the level of safety needs to be even higher, as they would be administered to healthy people; on the other hand, the fact that each tumour has its own characteristics complicates the possibility of making effective vaccines in advance of their appearance.

One of the options being explored is to test preventive vaccines in people with a very high risk of developing certain types of tumours. This is the case, for example, in Lynch syndrome, an inherited disorder that increases the risk of tumours such as colon tumours.

What types of cancer vaccines are there?

Multiple forms of vaccines are being tested. The general idea is to present antigens of the tumour to our defences, to make them react and strongly target the tumour. This can be done using, for example, proteins, DNA or RNA - as used in Moderna's and Pfizer's covid-19 vaccines, which took advantage of technology already being tested against cancer.

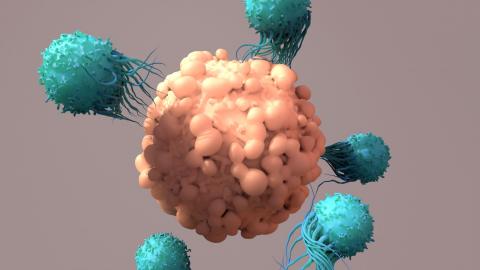

So-called dendritic cells - very important in the coordination of defences - can also be used, which are extracted from the patient, trained in the laboratory and then re-injected. The immune system is even being tested to activate and educate the immune system by boosting it directly, without the need to extract cells, so that it can make better use of the presence of the tumour itself to train itself. Under the common umbrella of the general idea, there are many different forms.

Which type of vaccine offers the most hope?

As Ignacio Melero, Professor of Immunology at the University of Navarra, researcher at CIMA and co-director of the Department of Immunology and Immunotherapy at the Clínica Universidad de Navarra, commented at a briefing organised by SMC Spain with journalists, there are high expectations for RNA vaccines using what are known as neoantigens. These are parts of the tumour that have arisen in the tumour but are not in healthy cells, which may allow a more potent response to be directed and, theoretically, with fewer side effects.

In the opportunity, however, there is also the penalty: these new candidate antigens would need to be identified each time, because they may be different for each patient. This would be the ultimate expression of personalised medicine, as vaccines would be designed to fit only one person. This would not only take time to prepare, but could also increase prices: "I dread to think how much they could cost," Melero acknowledged, "although I am also confident that, if they arrive and are really effective, the processes will be automated and become cheaper. That is at least my hope.

We have heard about universal cancer vaccines, but is it possible?

Occasionally, there have been news reports of universal vaccines, as if they could be used against any type of tumour. Sometimes this news has arisen as a result of RNA vaccines with neoantigens. However, what is universal here is not the vaccine, but the tool, because it allows the design of almost any antigen required. In reality, and as we have already explained, such vaccines are almost the opposite of universal, because they would be extraordinarily unique and personalised.

So is such a vaccine an impossible dream? "If you had asked me a few years ago, I would have said yes," Melero said. "However, we have recently seen cases of partial successes by vaccinating against proteins that are used by the tumour to stop the immune system and that may be present in different types of tumours.

This raises hopes, but they are unlikely to be completely universal and, in any case, they are being tested in combination with other treatments: they do not seem to be sufficient on their own, but would increase the efficacy of other types of immunotherapy.

Right now there is only one approved vaccine and it is no longer used, why, and is it reasonable to expect so much?

"Actually, the history of cancer vaccination is a long history of failures," Melero acknowledged. The only approved vaccine worked against metastatic prostate cancer, "but it is no longer used because it was a very complex procedure and other treatments emerged that were easier to administer". In fact, the company that marketed it went bankrupt.

Developing effective vaccines is not easy for many reasons. One is that you have to identify and select antigens that provoke a response. But it is also necessary to overcome the brakes that tumours often impose on our defences.

The expectation, however, seems justified, given the more than 300 clinical trials currently underway. The reasons for this are the increase in knowledge about immunity and immunotherapy and ways to make defences react, together with improvements in technologies that allow the best targets to be identified and to do so more quickly.

Can we expect new cancer vaccines to be approved in the short to medium term?

At the end of 2022, the companies Moderna and Merck (MSD) announced in a press release the results of a phase 2b trial of their RNA- and neoantigen-based melanoma vaccine. Targeted at a specific group of patients at high risk of relapse after surgery, the risk of recurrence or death was reduced by 44% in the first year. If these results are confirmed in the next phase of clinical trials, it may be the next vaccine to be approved. Roche and BioNTech companies are testing a similar strategy with several types of antigens.

Melanoma is the tumour type where the most research is being done and the most results are being obtained, because it accumulates many changes and this facilitates the design of vaccines.

What future is reasonable to expect?

Most likely, some vaccines will become part of the tools available to treat certain types of cancer and will be applied in combination with other therapies. Melero uses this analogy: if defences were a car, "vaccines would make it possible to start the engine, but once started, you have to release the brakes and, if possible, step on the accelerator".

The scientist's final message, despite the history of failure and the difficulty of the enterprise, is hopeful: "Immunotherapy is an exciting field and we expect major breakthroughs in different tools. In the last ten years the development has been dizzying and I think the best is yet to come. The proof is that in the 1990s only a few of us were doing this; now it has attracted the best talent and a lot of investment," he concludes.