First "Complete" Map of Brain Activity in Mice Revealed

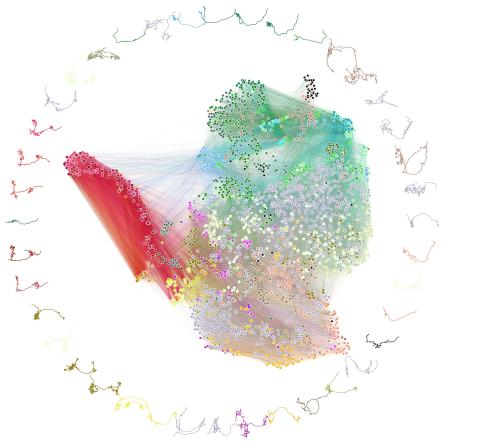

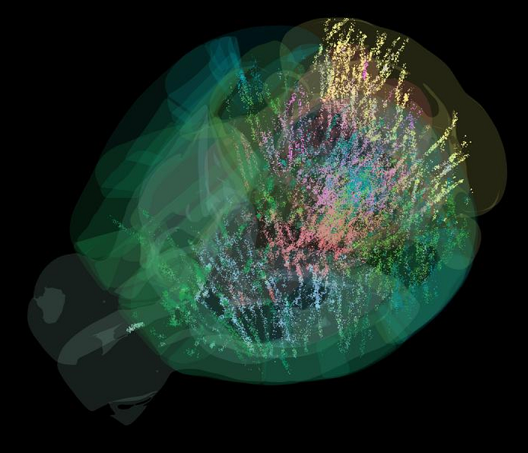

A team of neuroscientists from the International Brain Laboratory has described for the first time a virtually complete map of brain activity in mice during the decision-making process. To do so, they recorded the activity of more than half a million neurons across 12 different laboratories, representing 95% of brain volume. The map contradicts a hierarchical view of information processing and shows that decision-making is distributed in a coordinated manner across multiple brain areas. The results are published in two articles simultaneously in the journal Nature.

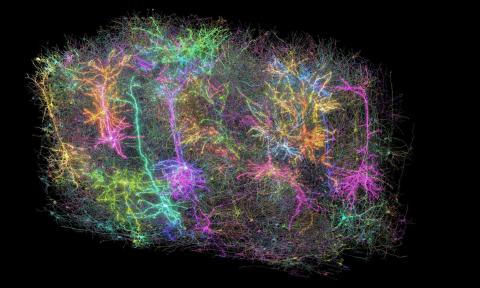

Brain map with 75,000 neurons analyzed / Dan Birman, International Brain Laboratory

Lerma - Mapa ratón (EN)

Juan Lerma

CSIC research professor at the Instituto de Neurociencias de Alicante (CSIC-UMH) and member of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Spain

These two studies are of unquestionable quality. Extreme rigor has been applied to ensure repeatable and entirely reliable data. These studies represent an enormous effort, as more than half a million neurons spread across 279 brain areas—practically the entire mouse brain—were analyzed during a common task involving sensory information processing and decision-making. Of this huge number of recorded neurons, approximately 75,000 were curated and selected for analysis due to their high quality and stability throughout the test.

The conclusions drawn from the first round of analysis represent a beginning rather than an end. The data are openly available to researchers, so anyone who wishes can perform further analyses. These initial conclusions corroborate aspects of brain function that were already intuited from the more limited studies available. It's as if we suspected how a movie would end without having seen the ending; now they've shown it to us. In short, the data show that, in decision-making, for example, many brain areas are involved, more than expected, while in sensory processing the areas are more distinct. In short, the brain functions more as a whole than in fragments when it comes to generating complex behaviors. Hence the need to study it more holistically than has been done so far, something that has been postulated for years.

The only limitations of this study are imposed by its complexity. We must keep in mind that when analyzing complex behavior, there are many aspects to consider that could distort the correlational analysis with such extensive neuronal activity. For example, when analyzing neuronal activity in the various brain structures related to reward (letting the mouse drink), it is difficult to separate the motor aspect of obtaining reward (licking) from its hedonic aspect (the pleasure of drinking). Both are encoded in neuronal activity. But as I say, the key point is that there is now a huge amount of information available, perfectly identified in the form of a high-resolution brain activity map, with which to perform further—and probably more complicated—analyses.

Rafael Yuste - mapa ratón

Rafael Yuste

Professor of Biological Sciences and Director of the Center for NeuroTechnology at Columbia University (New York), President of the NeuroRights Foundation and promoter of the BRAIN project

The articles demonstrate one of the technological approaches promoted by the BRAIN initiative: the use of high-density electrodes to record the activity of neural circuits. The original slogan of the BRAIN initiative was “to record all the activity of all neurons,” something that has already been achieved in smaller animals such as hydra and zebrafish larvae using optical methods, which are the other major focus of neurotechnology today. These articles, in fact, lag behind optical advances, as two years ago it was possible to optically map the activity of more than a million neurons in a mouse. In any case, these articles represent an important advance in the application to animals of a technology that is beginning to be used in patients. It is also noteworthy that this work has been carried out by a large consortium of laboratories, demonstrating that modern neuroscience and, in general, all biology, is becoming increasingly similar to physics, where large experiments are carried out in groups.

Dayan et al.

- Artículo de investigación

- Revisado por pares

- Animales

Findling et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Animals