Reactions: The lineage of the so-called 'swine flu' has passed from humans to pigs almost 400 times since 2009

Influenza A can cause influenza in humans, birds, pigs, and other mammals. In 2009 and 2010, a pandemic caused by the pdm09 strain—popularly called 'swine flu' because it contained genetic sequences from avian, swine, and human influenza—caused thousands of human deaths worldwide. Since then, this lineage has crossed over 370 times from humans to pigs in the United States, according to a study published in PLOS Pathogens. The research also indicates that the circulation of the virus among pigs may cause further evolutionary changes in this lineage, which would increase the risk of the virus passing back to humans.

Giovana Ciacci Zanella rubs a pig's snout to collect samples to detect the influenza A virus. Credit: M.Marti and A.Grimes, USDA (CC-BY 2.0).

Elisa Pérez - gripe porcina EN

Elisa Pérez Ramírez

Researcher in the Department of Infectious Diseases and Global Health at the Centre for Animal Health Research CISA-INIA, CSIC

This study is a great example of the importance of reverse zoonoses, that is, the transmission of pathogens from humans to animals (in this case, pigs).

Historically, little attention has been paid to this type of animal-human contagion, largely due to our anthropocentric vision of health, in which we tend to consider humans as victims of contagion, but never as its origin.

The H1N1 pandemic influenza virus is a zoonotic virus that arose on a pig farm in Mexico from a combination of genetic material from avian, swine and human influenza viruses. The virus managed to jump from pigs to humans and then fully adapt to its new host, effectively transmitting from person to person around the world. Just one month after the pandemic H1N1 virus had reached a worldwide distribution, the first cases of human-to-animal transmission were detected. The first outbreak occurred on a pig farm in Canada and since then the virus has jumped from humans to pigs hundreds of times, as confirmed by this study.

The main risk of these reverse zoonoses is that the animal host ends up becoming a reservoir of the pathogen in question. In other words, the virus adapts to the pig and continues to evolve in it, so that it can accumulate mutations that end up giving rise to a more dangerous virus, either because the seasonal flu human vaccines are less effective against it or because the Pre-existing human immunity against the parent strain does not protect against variants originating in pigs.

It is well known that the pig is a key species in the emergence of zoonotic influenza viruses. In fact, it is considered the main “shaker species”, since it is susceptible to swine, human and bird flu viruses. If a swine cell is infected at the same time by influenza viruses of various origins, a rearrangement of genetic segments may occur, giving rise to a new subtype capable of infecting various species. This is what happened with the H1N1 strain in 2009 and what could happen again at any time, especially in the current situation in which we are suffering from the largest avian flu epidemic in history, caused by the H5N1 subtype, which we know is it can also infect the pig.

The pig has been the species most affected by these reverse transmissions of the H1N1 virus, but it has not been the only one. Human-animal contagion has been confirmed in other livestock species such as turkey, in pets such as dogs, cats, and ferrets, in zoo animals, and in mink on fur farms.

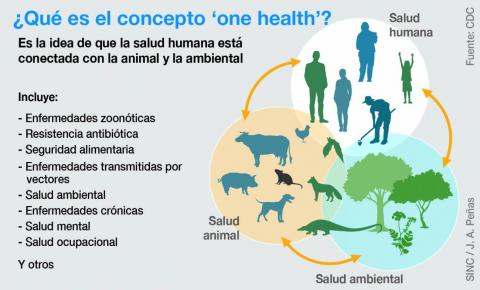

It is likely that all these species remind you of something. Indeed, all of them, except the turkeys, have recently been infected with another pandemic virus: SARS-CoV-2. In fact, there are many similarities between the two viruses, especially in the spectrum of species that they can infect and in the risk of the appearance of animal reservoirs that greatly complicate the control of the disease at a global level. Both examples remind us that zoonoses are transmitted in two directions and that ignoring this fact can have very serious consequences for our health and that of the planet. To fight against these viruses, it is essential that animal health and public health professionals work in coordination, accepting that everything is connected and that health will be global or it will not be.

Gustavo del Real - gripe porcina EN

Gustavo del Real

Senior scientist in the Biotechnology Department at INIA-CSIC

Since the start of the H1N1 influenza A (pdm2009) pandemic, numerous cases of transmission of this pandemic virus from humans to pigs (reverse zoonosis) have been documented in Europe and the USA. The vast majority of these infections occurred during the years since the pandemic, when the virus circulated in humans with its highest incidence, but transmission events have not stopped since then. This study describes the frequency of these human-to-pig transmission episodes in the US from the emergence of the 2009 pandemic to the present. The introduction and establishment of new viruses of human origin in pigs increases the heterogeneity of the viruses in this species and increases the chances of the origin of swine flu strains capable of inverse transmission to humans and causing new pandemics.

Similarly, a study carried out in our INIA-CSIC laboratory demonstrated the existence of at least three genetically different lines of the human H1N1pdm2009 virus in our pig herd, the result of independent transmissions of viruses of human origin. Once introduced into swine, the new H1N1pdm2009 viruses evolved independently from their human relatives through mutation and genetic exchange with other swine influenza viruses, giving rise to a wide diversity of influenza A viruses in our swine herd. Human influenza vaccines may partially protect against some of these swine viral variants depending on the degree of antigenic similarity.

Prior to the 2009 pandemic, there were also several cases of reverse zoonoses that contributed to shaping the genetic makeup of contemporary swine influenza viruses. This evolutionary closeness between swine and human influenza viruses explains the relative ease of reciprocal transmission of viruses between the two species. For this reason, close and constant surveillance of influenza viruses in both species is absolutely necessary to anticipate possible emergencies of swine flu viruses with pandemic potential and the reissue of another pandemic similar to or with worse consequences than the one suffered in 2009.

Special surveillance should be carried out on those people who, for professional reasons, have close and frequent contact with pigs: farmers, veterinarians, butchers, transporters, etc.

Alexey Markin et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Experimental study

- People

- Animals