What mosquitoes are we talking about?

Thousands of different species of mosquitoes have been described worldwide. In Spain, there are 63 species, says Roger Eritja, head of Entomology at Mosquito Alert to SMC Spain, a citizen science project coordinated by various public research centers. Most of these are native, such as Culex pipiens (common mosquito), a species present throughout Europe. The number includes three invasive species that arrive from other parts of the world, transported by traveling people, in vehicles, or through plants or used tires. These three species are:

-

Aedes aegypti (yellow fever mosquito, native to Africa), a species that was common in the country in the 18th and 19th centuries, now arriving sporadically.

-

Aedes albopictus (tiger mosquito, native to Asia), established in wide areas since 2004.

-

Aedes japonicus, established in Cantabria since 2018.

In this article we explained how to distinguish dangerous mosquito species and what to do if one bites you.

What diseases do mosquitoes transmit?

These mosquitoes are vectors of several arboviruses that can infect humans or other animals, and parasites like malaria.

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus can transmit yellow fever virus, dengue, chikungunya, and Zika.

Culex pipiens and Aedes japonicus are vectors of the West Nile virus.

Cases of these diseases can be imported—brought to Spain by a person infected in another country—or locally transmitted cases. It is important to remember that the entry of vector mosquitoes into an area does not indicate that diseases have already been transmitted: for that, infected patients must also arrive in the regions, notes Jacob Lorenzo Morales, director of the Institute of Tropical Diseases and Public Health of the Canary Islands at the University of La Laguna to SMC Spain.

Both the West Nile virus and its vector, the common mosquito Culex pipiens, are endemic in our territory, as explained by María José Sierra, head of the CCAES area, at an informative session on the National Plan for Vector-Borne Diseases held on June 17. “We are more concerned about the West Nile virus than dengue,” said Sierra, one of the national plan's coordinators. Dengue transmission is less likely, as it requires a series of conditions that are not yet met.

Regarding the symptoms, 80% of people infected with the West Nile virus do not show symptoms; 20% will have flu-like symptoms, and in less than 1% of cases, the infection can affect the brain, with severe cases of meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis.

Why are international agencies raising alarms?

Cases of infection—both indigenous and imported—are increasing significantly, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). In 2023, 130 indigenous cases of dengue were reported in the EU/EEA, nearly double the 71 cases reported in 2022, and a boom compared to the 73 locally acquired cases recorded over the entire period from 2010 to 2021.

There are also large outbreaks in other parts of the world, particularly in the Americas, leading to an increase in imported cases. “As of April 30, 2024, more than 7.6 million cases of dengue have been reported to the WHO, including 3.4 million confirmed cases, over 16,000 severe cases, and over 3,000 deaths,” the World Health Organization (WHO) published in a statement on May 30.

Additionally, there is an increase in the movement of people: in the first three months of 2024, a total of 5.7 million people entered mainland Europe from dengue-endemic areas in other parts of the world, more than double the total volume of travelers in all of 2023, noted Céline Gossner, principal expert in emerging and vector-borne diseases at ECDC, at an informational event held on June 11.

What will happen this summer?

“Faced with a summer that is expected to be complicated, entomological surveillance is crucial,” warns the Ministry of Health in a statement.

“The tiger mosquito [Ae. albopictus] is present and abundant in much of Spain. There will be virus importation, and the environmental conditions in the summer are suitable for local outbreaks,” said Gossner. “But we cannot predict whether there will be zero outbreaks or multiple outbreaks,” she added.

The Paris Olympics, which will take place during July and August, also pose a high risk of disease transmission, which French authorities are closely monitoring, added the ECDC expert.

Where are these mosquitoes in Spain?

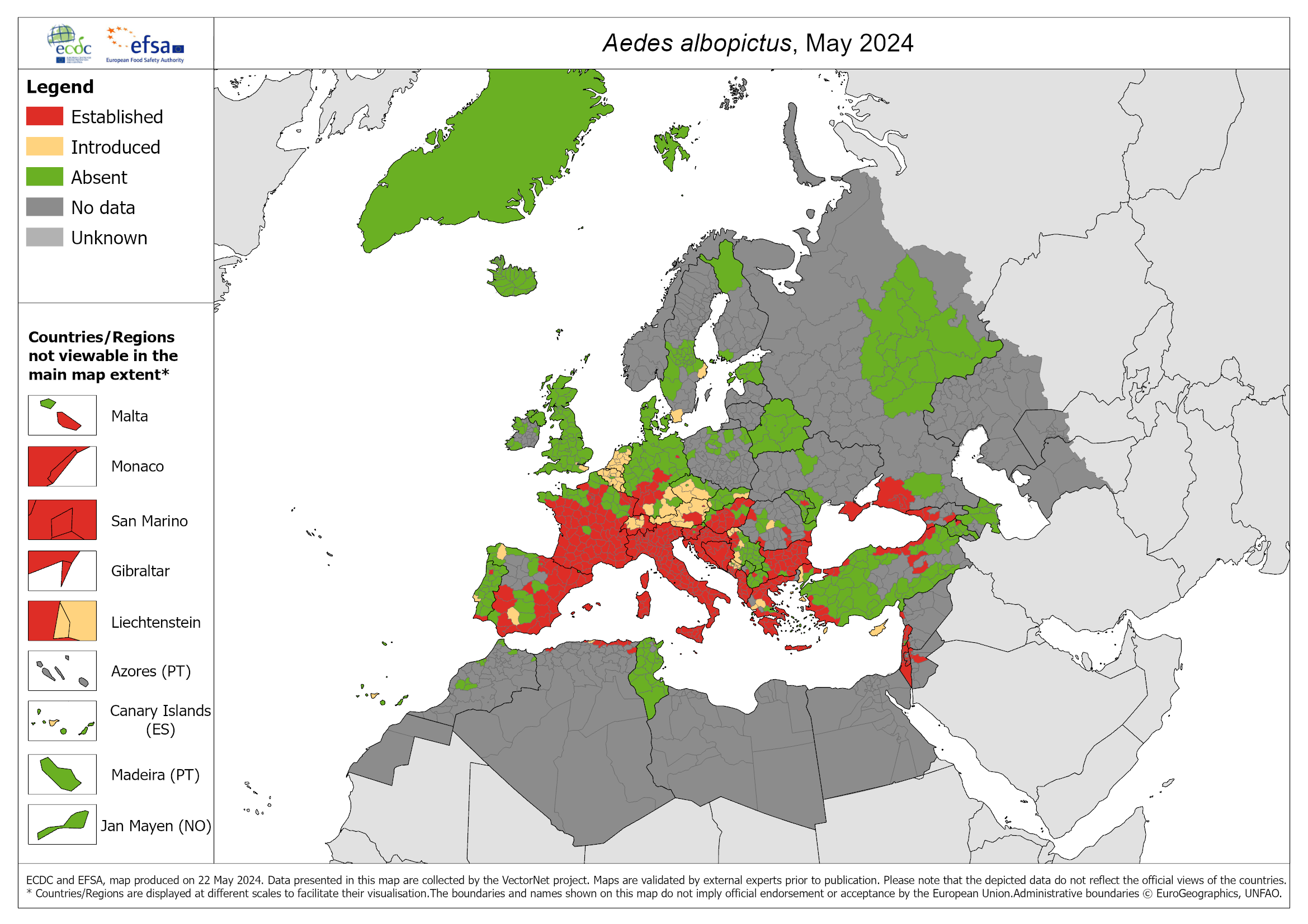

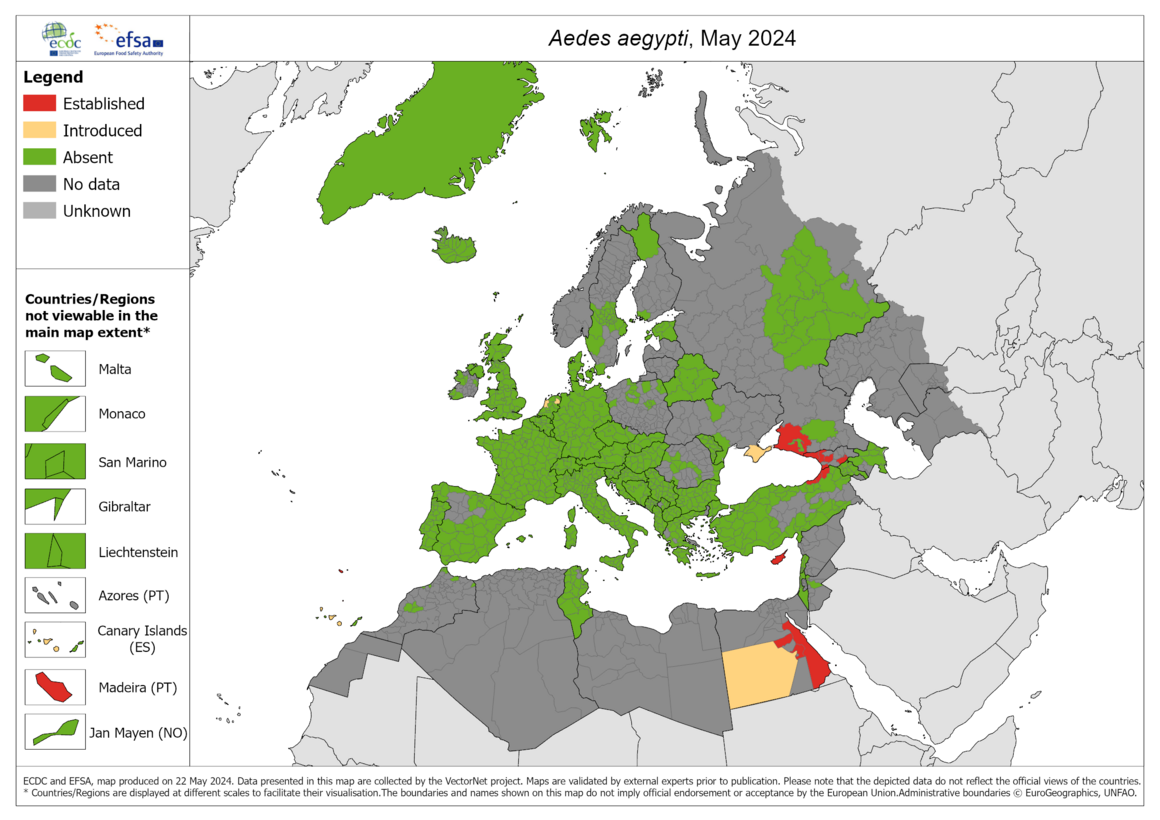

The ECDC publishes maps detailing the status of various native and invasive mosquito species across different regions of Europe. These are figures from administrative sources with field data that are updated approximately every six months. In Spain, this data is available by provinces.

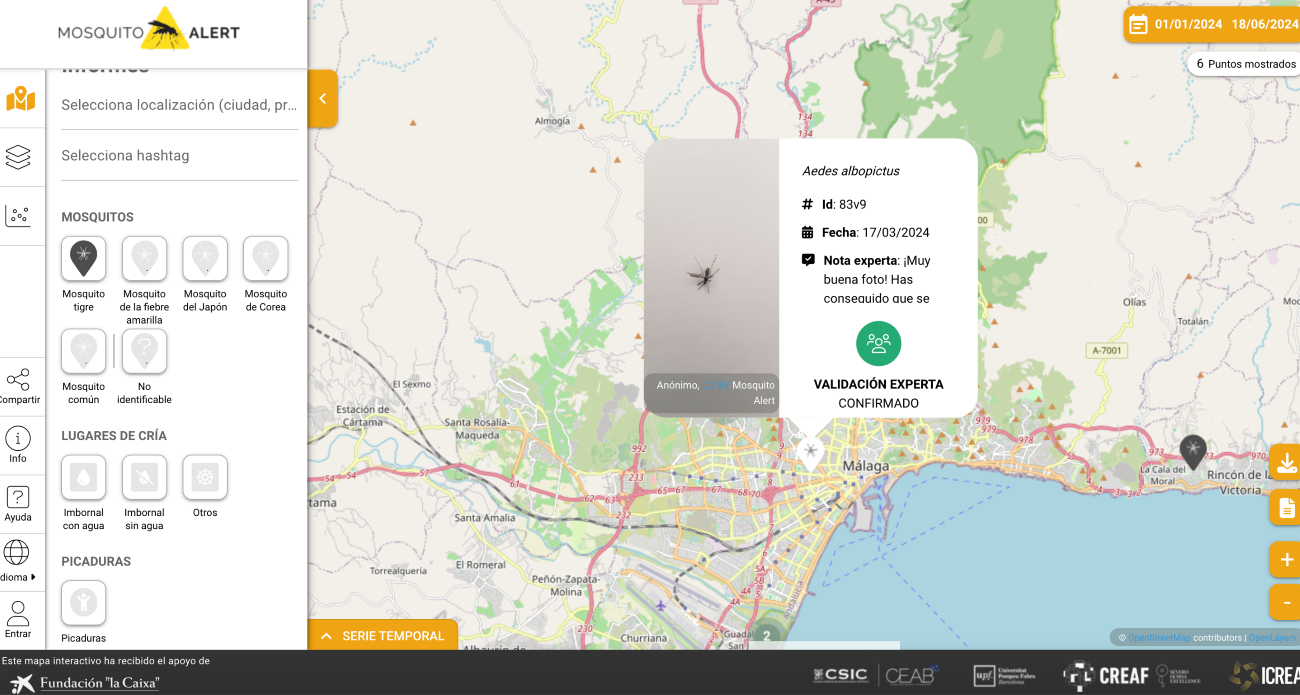

To obtain near real-time data and by municipalities, the maps of the Mosquito Alert project can be consulted online, which complements scientific monitoring of invasive species through citizen observations. Through their app, anyone can report the sighting of one of the studied mosquitoes. A team of entomologists validates the received photos before adding the result to the public maps. Since 2014, 21% of tiger mosquito discoveries in Spain were made through Mosquito Alert. When a species is detected in a municipality where its presence was not known, the system informs the CCAES, which alerts the autonomous communities.

The latest ECDC maps indicate that between October 2023 and May 2024:

-

Aedes albopictus (tiger) established itself (in red) in new areas of France and Germany; and was introduced (in yellow) in the Spanish provinces of Córdoba and Lugo, among other areas of Europe.

-

Aedes aegypti (yellow fever mosquito) was introduced (in yellow) in the Canary Islands; although it is still not established in the archipelago.

“Introduced means it can disappear again. Established means that the species has a self-sustaining population,” differentiated Andrea Gammon, ECDC director, at the press conference.

This is not the first time that Aedes aegypti has been introduced in the archipelago; in previous introductions, it has been detected and eliminated, explained Lucía García San Miguel, head of the CCAES area and also coordinator of the National Plan for Surveillance and Control of Vector-borne Diseases, at the journalists' workshop. However, “it is a matter of time before it becomes established. It is very difficult to control the mosquito,” she added.

Is the geographical range of mosquitoes expanding?

Yes, the global temperature rise increases the geographical range where species can establish themselves, both in latitude and altitude. However, climate change is also associated with prolonged drought, which “can be fatal for mosquitoes,” says Eritja to SMC Spain.

Furthermore, “the expansion of invasive species cannot be understood without human action,” continues the entomologist. We transport mosquitoes in our commercial activities and leisure travel. We allow them to thrive without rain, as “the tiger mosquito breeds larvae in small domestic containers, such as watering cans or barrels,” points out the expert.

Aedes aegypti has established itself on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus and in other more remote parts of Europe, such as Madeira and French territories in the Caribbean, according to the ECDC. “Its potential to establish itself in other parts of Europe is concerning due to its significant ability to transmit pathogens and its preference for biting humans,” warns the center in a statement.

Is the mosquito season lengthening?

Yes, the periods of activity during the year are also expanding. Normally, mosquitoes have their peak in summer before decreasing their activity and even hibernating in winter, explains Lorenzo Morales. Now, “warmer global climatic conditions are allowing mosquitoes and other arthropods not to have a stop in their life cycle,” says the parasitologist.

“We have seen from Mosquito Alert that in recent years tiger mosquitoes are appearing in a wider season, extending breeding in spring and autumn-winter,” confirms Eritja.

This year, the Andalusian Ministry of Health reported a case of West Nile fever in a five-year-old boy in the province of Seville. He was hospitalized for 10 days, and his symptoms started in early March, which is unusually early, according to ECDC sources in the briefing session. “Although it is an isolated case, it highlights that West Nile virus transmission can occur early in the year, probably due to suitable climatic conditions,” according to a statement from the agency.

Is this getting worse?

Yes, sources agree that the expansion of mosquitoes and the diseases they transmit will intensify in the future. A 2019 study, for example, estimates that by 2080, Aedes albopictus will be present in 197 countries and Aedes aegypti in 159 countries. “Along with global warming that allows the expansion and constant life cycle of these animals, the increase in population and urban areas further favors their expansion and multiplication,” summarizes Lorenzo Morales. “Remember that female Aedes tend to stay close to their food source, in this case, us,” he adds.

“The forecasts cannot be very optimistic in light of the evolution of recent years,” concludes Eritja. Besides the expansion of invasive species, the entomologist highlights several factors: “Recent large-scale epidemics in countries that are receivers and emitters of dense exchanges of people with Spain; the increasing detection of West Nile virus and the growing presence of cases in equines, birds, and humans; and the year-on-year increase in episodes of autochthonous transmission of exotic arboviruses in multiple European countries.”

Are there vaccines against the diseases they transmit?

- There is a vaccine against yellow fever, which has been in use for several decades. Some countries require a vaccination certificate for travelers entering their territory.

- There are two vaccines to prevent dengue approved in Europe: Dengvaxia (since 2018) and Qdenga (since 2022). These vaccines “are intended for people living in highly endemic areas, so to date they are not part of the toolkit for preventing or controlling dengue outbreaks in continental EU, where dengue is not endemic,” Gossner noted.

- On May 31, 2024, the European Medicines Agency recommended approving the first vaccine against chikungunya in adults in the European Union. The authorization decision is now in the hands of the European Commission and then member states will determine its use and possible reimbursement.

- There is no vaccine against the West Nile virus in humans, but there is one for horses.

- There are vaccines in development against Zika. Within a month, Moderna is expected to complete a phase 2 clinical trial in the United States and Puerto Rico; and in March, Valneva announced a phase 1 clinical trial in the United States.

What preventive measures can we take?

On an individual level, mosquito bites can be prevented by wearing long-sleeved clothing and pants, using repellents, mosquito nets, and air conditioning. These measures are particularly important during the three weeks after returning from an area where Aedes mosquitoes are present, to reduce the likelihood of secondary transmission by infected people, Gossner said at the ECDC event.

It is also essential to avoid the accumulation of standing water in flower pots, buckets, pet drinking bowls, tarps, etc. If water storage is necessary, the container should be covered. “The tiger mosquito takes advantage of small volumes of water to develop, so attention must be paid to small details,” notes the Mosquito Alert website, which provides many practical tips.

“It is about combining citizen programs, research, pest control, and health management involving the academic field, public administration, citizens, and the private sector,” details Eritja. These are “toolkits that only make sense together,” he adds, emphasizing the importance of citizen science to inform and “allow people to participate in their solutions alongside administrations.”

The approach will differ according to the mosquito species, García San Miguel explained at the CCAES event. In the case of Aedes albopictus “which is already among us, [...] we will not be able to eradicate it, but we can try to reduce its density.” But with Aedes aegypti, “which is a hyperinvasive species, if it enters, we want to eradicate it.”

“National and regional surveillance systems prevent new introductions, as is the case with current alerts in the Canary Islands with Ae. aegypti—Lorenzo Morales highlights. Without these sentinel systems, we would be lost.”