Reaction to the new Spanish covid-19 prevention and control strategy

The Public Health Commission has updated the Covid-19 Surveillance and Control Strategy, which will come into force on Monday 28 March. From then on, as long as indicators of healthcare utilisation are at low risk, diagnostic testing will focus on vulnerable individuals and settings and severe cases. Surveillance will focus on these groups.

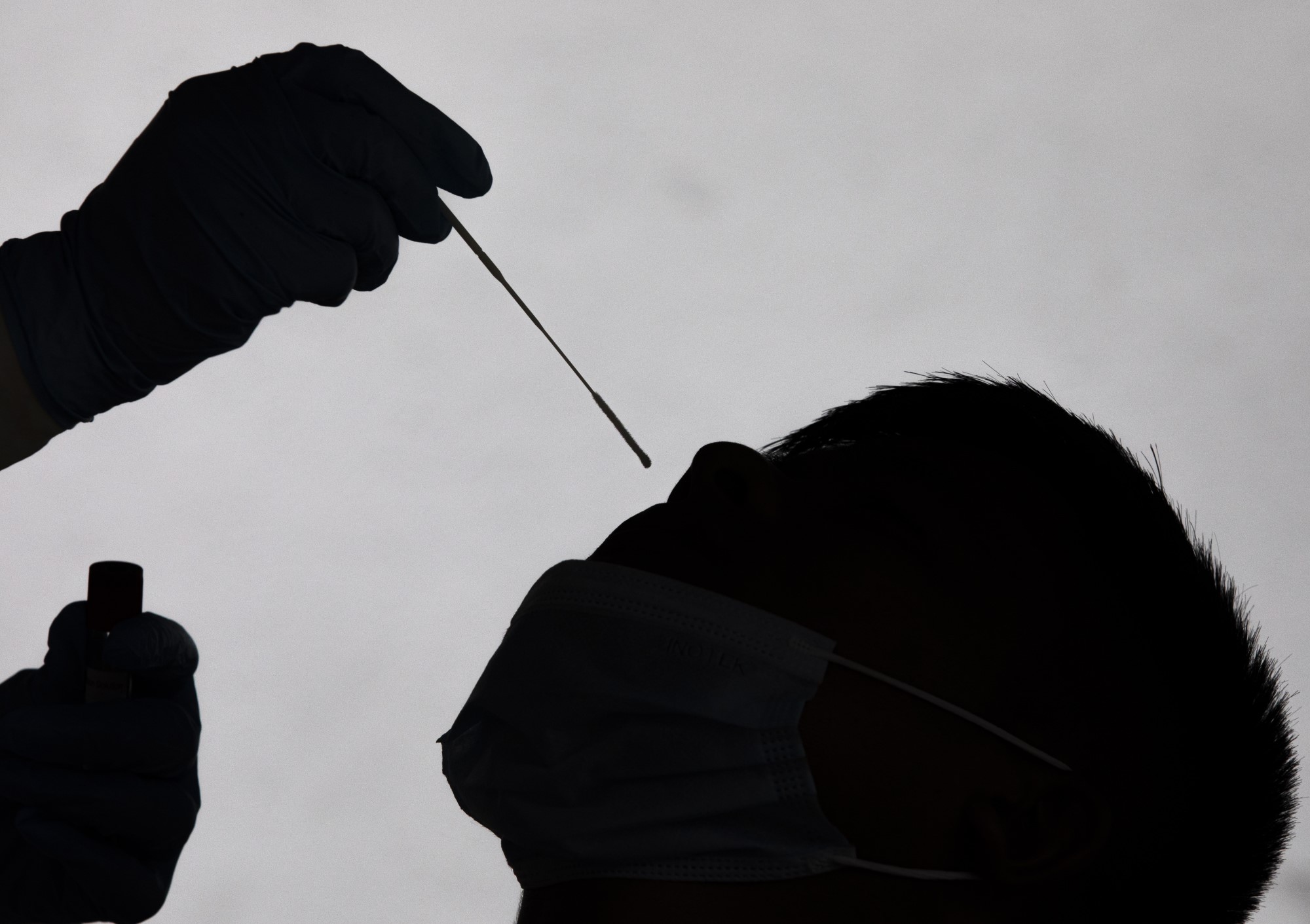

A health worker performs a PCR test. EFE/EPA/NARENDRA SHRESTHA

Adrián Aginagalde - cambio plan

Adrian Hugo Aginagalde

Spokesperson of the Spanish Society of Preventive Medicine, Public Health and Health Management (SEMPSPGS), Head of Service of the Epidemiological Surveillance and Health Information Unit of Gipuzkoa and, previously, Head of Service of the Population Screening Programmes Unit at the Ministry of Health

The change in the epidemiological surveillance model is conditioned by greater transmissibility and a lower hospitalisation and case fatality rate.

An attempt is made to address the intrinsic difficulty of respiratory infections, which is to try to carry out universal surveillance (of all cases) through diagnostic confirmation tests; something that has not been achieved in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) or influenza (influenzavirus).

To this end, a sentinel (sample) model of mild and severe cases is established, combined with syndromic surveillance (of symptomatic cases) and virological surveillance (variants) and supported by additional tools (monitoring of temporary disabilities and wastewater).

The challenge is to design a transition between the two models, something that has not been done before, and with a disease of pandemic magnitude, with a much greater healthcare impact than other acute respiratory infections and the capacity to generate between two and three acceleration phases per year. Given this gap in knowledge and models of how to monitor in order to be able to react when necessary, the strategy makes a transition to surveillance of mild cases through medical record codes and of severe and vulnerable cases with a higher risk of hospitalisation. The aim is to be able to anticipate with sufficient accuracy sudden increases in the pressure of care.

At the same time, given the very high transmissibility of Omicron, which prevents the identification of contacts (the programmes collapsed in December) and concentrates its transmission in the days prior to the onset of symptoms, it is time to reconsider control measures such as isolation due to loss of effectiveness. It was an extraordinary measure, not widely applied with such a prevalent disease, never before used in an acute respiratory infection and which, in the absence of quarantines, due to the transmission of asymptomatic people, had limited effectiveness and important consequences.

Salvador Peiró - cambio plan

Salvador Peiró

Epidemiologist, researcher in the Health Services and Pharmacoepidemiology Research Area of the Foundation for the Promotion of Health and Biomedical Research of the Valencian Community (FISABIO) and Director of Gaceta Sanitaria, the scientific journal of the Spanish Society of Public Health and Health Administration (SESPAS)

The Public Health Commission's decision is reasonable in the current context in Spain, with a very high proportion of people with a complete regimen, of people with booster doses (particularly high in older people, who are the ones who produce the most serious cases) and also of people who have passed the infection. This last aspect is relevant because the unvaccinated have caused a disproportionate number of severe cases and, foreseeably, most of them will have passed the infection and it will be difficult for them to repeat this half of the occupancy of the Covid ICU.

Although spikes or sawtooths in transmission and, of course, new variants are to be expected, the population has significant protection against severe disease which, at least in theory, may allow covid-19 to be managed in a similar way to other upper respiratory tract infections where aetiological diagnosis (testing) and isolation are unusual.

More uncertain is how it will be operationalised to minimise the impact of outbreaks on some vulnerable populations. When transmission is high (and we are still at a time of high transmission, although the current testing strategy does not allow for accurate quantification) it is difficult to prevent it from reaching nursing homes (which will now be six months after booster doses) and vulnerable groups. If transmission increases in these vulnerable groups, and even though the proportion of severe cases is much lower now than before Omicron and the third doses, it will lead to hospitalisations and deaths.

Nor have epidemiological surveillance measures been articulated (they have been postponed to next year) to replace the current ones, or alternative measures to warn of spikes in vulnerable populations in advance of the - later - indicators of hospitalisation.

In short, a reasonable decision, albeit with some uncertainty about its impact, and one that should be accompanied by other measures to anticipate possible upturns, especially those affecting population groups at higher risk of developing severe covid.

Pedro Gullón - cambio plan

Pedro Gullón

Social epidemiologist and doctor specialising in preventive medicine and public health at the University of Alcalá

I think we have to distinguish how this change affects COVID-19 surveillance and monitoring, which are different.

On the one hand, in terms of surveillance, it will mean that the total number of cases will no longer be as comparable to other times in the pandemic. However, at no point in the pandemic have we ever detected 100% of asymptomatic cases because our surveillance system was not up to it. Although at some points we have come close to very high detections, in the sixth wave we were already applying de facto detection only of symptomatic cases because of the inability to diagnose everybody. I do not think this is extremely dangerous for surveillance because the other indicators (incidence in vulnerable groups, hospital occupancy...) will not be affected by this change, and it is part of a transition in the more global public health surveillance system.

In terms of control, it is true that the lack of isolation for asymptomatic individuals presents a potential risk of increased transmission, or difficulty in controlling transmission. However, isolation and quarantine as a pandemic control strategy has limitations, both because of the ability to reach everyone, and because the quarantine part was no longer in place. By this I mean that the effect on transmission is likely to be small, but it will have an effect.

I think that, in short, this change should be seen as a transitional process to make surveillance and control sustainable over time. We cannot live in public health services in constant emergency, and I think these changes are more about making surveillance and control of covid-19 sustainable in the medium term and not about forgetting the pandemic. But for it to really be a shift towards sustainability and not towards abandoning pandemic control, we have to be aware that there are many more control tools that can be at hand in case they are needed.

Manuel Franco - cambio plan

Manuel Franco

Head of International Relations at the Spanish Society of Public Health and Healthcare Administration (SESPAS), organiser of the 2026 European Public Health Conference (EUPHA), Ikerbasque Research Professor at the Basque Centre for Climate Change (BC3) and professor and researcher at the universities of Alcalá and Johns Hopkins

Surveillance is always dynamic and adaptive to circumstances. This has been the case during all waves and phases of the pandemic. The step taken is important, well thought out and positive.

Moreover, the change in surveillance is not a change in one Autonomous Community or country, but what is going to happen in Europe and worldwide.

Surveillance through sentinel centres is very good in Spain for different pathologies. For example, influenza and childhood obesity, among others.

Primary care must be able to return to its "normal" tasks. Pandemic control must always be improved and strengthened from a public health and primary care perspective.