Reaction: humanised kidneys developed in pig embryos up to 28 days old

Scientists have successfully developed pig embryos whose kidneys contain 50-60% human cells. Gestation was terminated at 25-28 days, and the organ structure was normal. According to the press release accompanying the article, "this is the first time that a solid humanised organ has been grown inside another species, although previous studies have used similar methods to generate human tissues". The results are published in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

Humanised kidneys developed in pig embryos / Wang, Xie, Li, Li, and Zhang et al. / Cell Stem Cell

Riñones - Matesanz (EN)

Rafael Matesanz

Creator and founder of the National Transplant Organisation.

The research group at the University of Canton [China] adds important advances in one of the avenues that has generated most interest over the last few years, within the long march of biomedical research to develop a modela for the production of organs suitable for transplantation by using pigs as a vehicle animal—which already started in the last century.

This research involves the creation of human-pig embryonic chimeras using pluripotent stem cells, so that the animals could serve as incubators for hypothetical customised organs created from the patient’s own cells, thereby avoiding the risk of rejection. Within this line of research, which has been developed over the last decade, the figure of [Spanish] scientist Juan Carlos Izpisúa, based in California, stands out, as well as that of Japanese researcher Hiromitsu Nakauchi. Izpisúa’s research has demonstrated the possibility of hybridisation between two apparently similar but genetically very different species—such as the mouse and the rat—achieving the development of mouse organs in rats, including the gall bladder that rats don’t have.

Continuing along these lines, in 2017, in collaboration with the Catholic University of Murcia, Izpisúa published in Cell for the first time the creation of chimeric human embryos in large animals, specifically pigs. Implanted in female pigs, they could grow until they were three weeks old, given the legal impossibility in Spain to go beyond that date. No organs were formed, as the aim was simply to demonstrate that human cells could be integrated into a species far removed from humans.

Already at that time, several serious problems were pointed out when it came to continuing the research. On the one hand, this technique had a low efficiency, with a little more than 1% of the implanted embryos being successful, a very low percentage for the intended purpose. On the other hand, in order to develop kidneys or other humanised organs inside pigs, it is necessary that the pigs do not develop their own, which requires specific manipulations with deletion of the responsible genes.

Moreover, the creation of human-animal hybrids, beyond a certain stage, is subject to severe ethical and legal restrictions in most countries. In fact, in 2019, the same authors published in Nature the creation of human-monkey hybrid embryos, but moving the research to China (it wouldn’t have been possible in the USA or in Spain) and stopping the experiment at week 14— the moment when the development of the central nervous system begins, which implies a high level of risk. At the same time, Nakauchi, working between Tokyo and Stanford, obtained permission from the Japanese government to create hybrid embryos of human cells with animals, in this case rats, to implant them in these animals and carry the pregnancy to term.

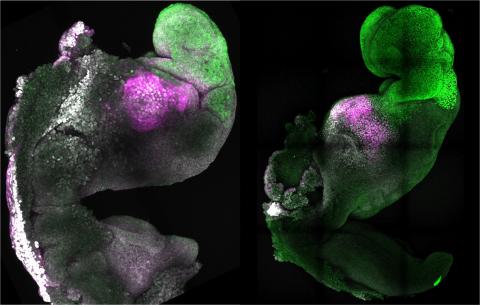

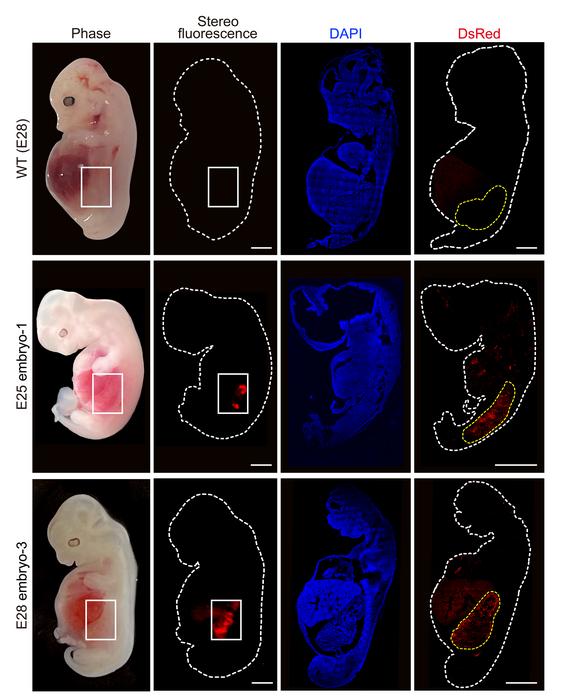

The current paper by the University of Canton group aims to find solutions to many of these obstacles. Carried out in China for the reasons outlined above, it is the first time that an entire human-pig chimeric organ has been created using the pig as an incubator.

After the animals were sacrificed at 25-28 days, kidneys with a normal structure and 50-60% human cells were extracted, which is very promising indeed.

To do this, they created a ‘niche’ in the pig embryo by CRISPR deletion of two genes on which kidney formation depends, so that human cells would not have to compete with porcine cells. They used specifically prepared human pluripotent cells and grew the embryos before implantation in special culture media.

These measures greatly increased the efficiency of the procedure, which was one of the weaknesses of former experiments. In addition, the presence of human cells outside the ‘niche’ was found to be very limited. This is very important, because the invasion of reproductive tissues or the central nervous system, with the consequent risk of uncontrolled creation of human-pig hybrids, has been one of the main ethical problems of these procedures.

The next steps will be to allow embryos to grow longer and to start doing the same with other organs and tissues, although the kidney is undoubtedly the most sought-after organ for transplantation. The authors themselves acknowledge that the clinical use of this technology is years away, but it is a major achievement on the road to unlimited organ production for transplantation.

Wang et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Experimental study