Reactions to study claiming that a single genomic change led to increased neuronal formation in modern humans

A single amino acid change in a protein (TKTL1) may have given modern humans an advantage over their older contemporaries, such as Neanderthals, by allowing greater neocortical neuronal formation, according to research published in Science.

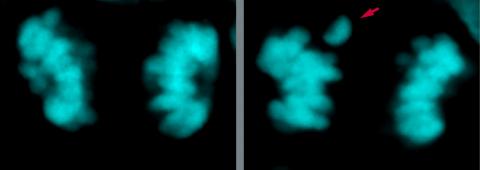

Image of a dividing radial basal radial glial cell, a type of cell that produces neurons during brain development. Author: Anneline Pinson.

Víctor Borrell - gen humanos neandertales EN

Víctor Borrell

Research Professor at CSIC at the Institute of Neurosciences (Alicante)

Dr. Svante Pääbo is a pioneer in the study and sequencing of human ancestral genomes, particularly Neanderthal, and Dr. Wieland Huttner is pioneer in the study of embryonic brain development and its human-unique aspects. Both scientists are celebrities world-wide in their respective fields. In this study they worked together to identify the differences in brain development between modern humans and Neanderthal, to understand what characteristics may have given an advantage to modern humans and their evolutionary success. One of the features typically different between our brain and that of Neanderthals is the frontal lobe, important for higher cognitive functions, which is greatly enlarged in modern humans.

Comparison between the genomes of Neanderthals and modern humans have shown that there are very few differences in their sequence, affecting a small number of genes and proteins. Few of these proteins have only a single change in their sequence of aminoacids (the building blocks of proteins), and yet these may modify the properties of such proteins and, thus, their function. One of these proteins is called TKTL1, abundant in the embryonic human cerebral cortex, particularly in the frontal lobe. In this study, the researchers study the effect of this single aminoacid substitution on cerebral cortex development to try to understand differences in embryonic brain development between Neanderthals and modern humans.

To study the effect of this difference in embryonic cortex development, the authors overexpressed either the modern or the ancient TKTL1 in embryos of mouse (with a small and smooth cortex) and ferret (with a large and folded cortex). They found that in both cases modern but not ancient TKTL1 increased the abundance of bRG cells, a very special type of cortical progenitor cell with a high capacity for producing cortical neurons. Increased bRG numbers further translated into increased numbers of cortical neurons of a certain kind, those found in the more superficial part of the cortex and typically most abundant in humans and primates as compared to other mammals. In ferret, these changes further modified the size and pattern of cortical folds. The authors also performed complementary experiments, removing the native TKTL1 from human cortical progenitor cells, or expressing the Neanderthal version, and in both cases this had the opposite effect on bRG abundance and neurogenesis, as predicted. Finally, the authors studied the mechanism of action of TKTL1. This protein is known to be important in the metabolic pathway for the synthesis of fatty acids, so the authors blocked directly three of the steps of this pathway (one before the action of TKTL1, and two after its action) while leaving the native TKTL1 unmanipulated. The result again was a reduction in bRG specifically, while leaving other types of progenitor cells unaffected.

The relevance of these findings is that they demonstrate the critical importance of this single aminoacid change between Neanderthals and modern humans in the embryonic development of their cerebral cortex, which led to much increased progenitor cell proliferation and neurogenesis in modern humans. The fact that TKTL1 is involved in the pathway for fatty acid synthesis, this shows the potential key importance of lipid metabolism and lipid composition in brain development, a completely new and unexplored research avenue. Because TKTL1 is most highly expressed in the frontal lobe in modern humans, the results of this study further suggest that this small genetic change may have been key in the characteristic expansion of the frontal lobe in modern humans as compared to ancient humans and other non-human primates, acquiring its typical modern shape. Although some results from this study suggest that TKTL1 expression may influence the amount and pattern of cortex folding, which is critical in cognitive performance, reaching this conclusion needs to more accurate work be done, in the ferret and possibly in primate models. How TKTL1 and fatty acid metabolism actually condition progenitor cell lineage and amplification remains a very intriguing and fundamental question to be solved in future studies.

This study is an important step in our understanding of which differences with Neanderthals may have conferred us some advantage, intellectual or of any other kind, also showing that small changes at the genomic level may have large consequences.

Emiliano Bruner - gen humanos neandertales EN

Emiliano Bruner

Researcher at the National Centre for Research on Human Evolution (CENIEH)

Neandertales y otros simios y descubrieron una sustitución de aminoácidos única codificada en el gen TKTL1 de los humanos modernos. Cuando se colocó en organoides o se sobreexpresó en cerebros de ratones y hurones, Pinson et al. descubrieron que la variante humana de TKTL1 (hTKTL1) impulsaba una mayor generación de neuroprogenitores de la glía radial basal (bRG) que la variante arcaica, lo que provocaba la proliferación de neuronas neocorticales. La interrupción de la expresión de hTKTL1 o la sustitución de hTKTL1 por la variante arcaica en el tejido neocortical fetal humano y en los organoides cerebrales dio lugar a una menor generación de bRG y de neuronas. "En conjunto, estas observaciones abren el camino para descubrir más

Anneline Pinson et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Animals

- In vitro