Synapses in individual neurons do not follow a single strategy during learning as previously thought

A new study sheds light on how the brain adjusts its ‘wiring’ during learning, concluding that different dendritic segments of the same neuron follow different rules for communicating through their connections - synapses. The findings challenge the idea that neurons follow a single learning strategy and offer a new perspective on how the brain learns and adapts its behaviour. The work, carried out in mice, is published in the journal Science.

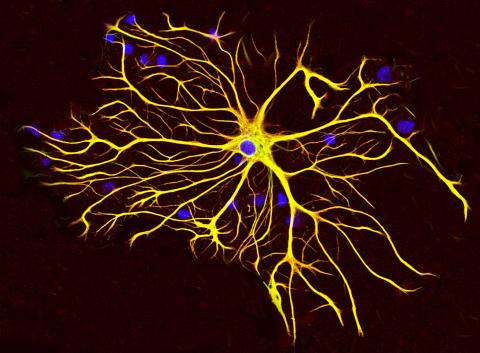

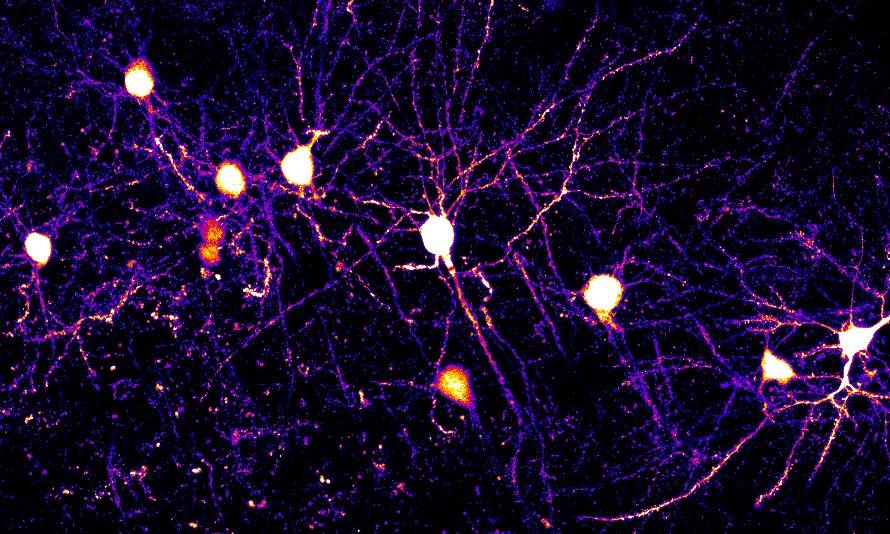

Cortical neurons and their branch extensions known as dendrites. Credit: William J. Wright.

Daniel Tornero - sinapsis neuronas

Daniel Tornero

Lecturer at the University of Barcelona (UB) and head of the Laboratory of Neural Stem Cells and Brain Damage at the Institute of Neurosciences of the UB

The press release is a good summary of the article. The results are obtained using a very precise technology (tracking neuronal activity in vivo in the brains of mice using fluorescent calcium indicators and 2-photon, or multi-photon, microscopy), which we also use in our lab, and which they have managed to adapt to the needs of their study in a brilliant way.

For years, scientists have known that some synapses get stronger while others get weaker when we learn, but we didn't know why some synapses change and others don't. In this paper, researchers show that neurons do not follow a single rule when learning, as previously thought. Each neuron can use several rules at once, depending on where in the cell the synapse is located.

This discovery changes what we knew about how the brain solves the so-called ‘credit allocation problem’, which is how the smallest components of our brain (such as synapses) know whether they are helping overall learning.

The study is descriptive, based on direct observations, and does not speculate on the interpretation of its results. It also provides a comprehensive analysis of the mechanism by which this process takes place in mammals, using very precise and novel technology. He notes different applications, but leaves that for future studies.

The most important limitation is that the study is carried out in animals, rodents, and not in humans. Knowing the vast differences between our brains and those of mice, especially in complex information processing such as that which occurs during learning, we might speculate that the same processes might be slightly different in humans. In fact, as a curiosity, studies have been carried out in which human cells have been introduced into the brain of a mouse (what we call a chimera) and different (enhanced) capabilities could be demonstrated in these animals (I could provide a reference, but I don't think it is relevant).

The results have important implications for the field of neuroscience. They certainly help us to better understand how the brain works and what goes wrong when it suffers from disease. It may also help us design better strategies to repair the brain when it is damaged. Finally, more in the technological than the biomedical realm, it could inspire new ways of creating artificial intelligence, with networks that use multiple rules like real neurons. The designs of artificial neural networks used in deep learning have always been inspired by how our brains work, and so this new breakthrough may provide new ideas on how to make this tool more powerful and efficient.

Ignacio Morgado - sinapsis neuronas EN

Ignacio Morgado

Professor Emeritus of Psychobiology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and full member of the Spanish Academy of Psychology

Using advanced in vivo neuroimaging techniques, this article describes the functional dynamics and the different synaptic changes that occur in different types of dendrites (basal or apical) of the same neuron in the motor cortex of the rodent brain as the basis of the synaptic plasticity that makes learning possible.

Apart from the modern imaging technique used, these findings reveal that the mechanisms of synaptic potentiation in the mammalian brain are more varied and complex than previously known. The work is of particular interest to specialists in precise neuronal physiology.

Wright et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Animals