When and where does COP29 take place?

The Climate Summit or COP29 will take place in Baku, capital of Azerbaijan, from 11 to 22 November 2024. As was the case in 2023 with its predecessor city, Dubai (of the United Arab Emirates), its choice came as a surprise given that Azerbaijan is an oil and gas producing power. A few days ago a report was made public denouncing the huge expansion of fossil gas production that is planned in the country over the next decade through its state oil and gas company, SOCAR, as reported by The Guardian.

The summit is chaired by Mukhtar Babayev, the country's minister of ecology and natural resources, who led Azerbaijan's delegation to the previous five COPs. Before entering politics, he worked for SOCAR.

What does the acronym POP stand for and when did it start?

COP stands for the United Nations Conference of the Parties on Climate. This conference is the decision-making body of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The convention was adopted in New York (USA) in 1992, entered into force in 1994 and has been ratified by 198 parties - 197 states and the European Union.

The number 29 of this COP means that it is the 29th meeting of this conference. The first was held in Berlin in 1995. COPs are held annually - except in 2020, due to the pandemic - where countries meet to take action to achieve the climate goals agreed under theParis Agreement- which was reached at COP21 in Paris in 2015 - and the UNFCCC.

What are the unfinished business of COP28 in Dubai?

Although in Dubai the participating countries, after lengthy negotiations, managed to reach a historic agreement by mentioning ‘transitioning away from fossil fuels’ for the first time in the Global Stocktake document, many issues remained unresolved.

‘Relevant issues related to the call for the parties to abandon fossil fuels, such as the transitioning away or the role of transition fuels, need to be clarified,’ Carlos de Miguel Perales, lawyer and professor of Civil and Environmental Law at the Faculty of Law at ICADE (Universidad Pontificia Comillas), tells SMC España.

Another pending issue, according to the expert, is to specify the operation of the damage and loss fund, and to review the national contributions of the countries (known as the NDCs). In addition, all countries should present their national adaptation plans by 2025.

‘For at least three COPs now, the financing of climate damage has become an important and urgent issue,’ Fernando Valladares, CSIC researcher and associate professor at the Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid, told SMC Spain.

For at least three COPs now, the financing of climate damage has become an important and urgent issue

Fernando Valladares

In his opinion, the approach of the countries of the global north helping the countries of the global south should be changed and the concept of debt for climate should be adopted. ‘Forgive them debt so that they conserve carbon sinks, conserve nature and use the money they would have to pay us to mitigate climate change. It would be a tremendous and great collective decision,’ he says.

What are the objectives of this summit?

The main objective is to avoid exceeding the limit of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. ‘The window of opportunity is closing and we must focus on the need to invest today to save tomorrow,’ the organisation argues. It calls for deep, fast and sustained emission reductions.

Increasing ambition is another of the constant criticisms of these summits and COP29 has set this as a goal. Another pillar is what they call ‘enabling action’ with the help of finance. This would be about turning ambition into action to reduce emissions, adapt to climate change and address loss and damage.

And finally they want the summit to be ‘an inclusive process for inclusive outcomes’. The first list of members of the COP29 organising committee did not include any women, but following criticism, several female experts were added. De Miguel Perales recalls that one of the pending tasks in Baku will be to adopt a decision on climate change and gender.

How will Trump's victory affect the development of this COP?

Without being present - he will not take office until January - there will be a clear protagonist at the meeting: Donald Trump. His second victory as president of the United States is a new challenge for current international climate policy, given that he decided to abandon the Paris Agreement and has denied the existence of climate change on numerous occasions, among other measures taken outside the scientific evidence.

‘The whole COP is going to be focused on the impact of Trump's victory. I was at the 2001 summit when Bush announced that he was not going to ratify Kyoto and nothing else was discussed. On that occasion the EU decided to go ahead and convinced Russia to ratify Kyoto, with quite a few concessions, and eventually Kyoto came into force in 2003 without the US. I don't think that on this occasion the effect will be similar, as Russia doesn't seem to be in favour,’ Alejandro Caparrós, Professor of Energy Economics at the University of Durham (UK) and research professor at the CSIC, explains to SMC España.

The economist recalls that, when Trump decided to pull out of the Paris Agreement, the impact was more modest than initially expected, as the rest of the countries clearly opted to go ahead without the US. ‘It is possible that countries have already discounted the fact that the US is constantly changing its mind and that its climate change policy is a matter of change. In this case the impact will be small,’ he argues.

A view shared by Friederike Otto, Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Environmental Policy at Imperial College London (UK). ‘The US has never been a great team player at COPs, regardless of which party is in government. People don't go to COPs expecting the US to push for more ambition. When Trump left the Paris Agreement in 2016, many governments still stuck to their plans. As always, other countries need to step up at COP29,’ he told the UK's SMC.

An analysis by Carbon Brief indicated that a Donald Trump victory in the presidential election could lead to a 4 billion tonne increase in carbon dioxide emissions in the US by 2030, compared to Joe Biden's plans.

This additional 4 billion tonnes would cause more than $900 billion worth of global climate damage and is equivalent to the combined annual emissions of the EU and Japan, or the combined annual total of the world's 140 lowest emitting countries.

I don't think any major decisions will be taken at this summit, as everyone will be ‘waiting for Godot’

Alejandro Caparrós

‘I don't think any major decisions will be taken at this summit, as everyone will be ‘waiting for Godot’. There will be a statement indicating the intention to go ahead with the Paris Agreement,’ Caparrós stresses.

What is the position of the European Union?

On 8 October, the European Council adopted conclusions in the run-up to COP29 on climate finance. ‘The EU and its member states are committed to the current target of developed countries to collectively mobilise $100 billion per year in climate finance by 2025. This target was met for the first time in 2022,’ they stress in a statement.

The EU body stresses that the EU and its member states are the world's largest contributor to international public climate finance, and since 2013 have ‘more than doubled’ their contribution to climate finance in support of developing countries.

The European Council stresses that the main objective of the summit will be to negotiate a new quantified collective goal (QCG) beyond 2025. The NCQG is provided for in the Paris Agreement: governments agreed to set a new climate finance target for 2025 to support developing countries in their climate actions. This will succeed the previous target set in 2009 at the Copenhagen Summit, where developed countries committed to mobilise $100 billion per year until 2020 to meet the needs of developing countries. In recent months, negotiations on the new target have highlighted the wide gaps in reaching agreement.

‘It is an outdated, old target that is not harmonised. I remember after Copenhagen that it seemed that it was only a matter of months before the financial mechanisms were found, but years have passed and here we are. Moreover, it is laughable because it has become so small,’ says Valladares.

‘There will be a lot of talk about adaptation and the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG),’ says Caparrós. ‘There will be some progress in this field, but I don't think it will be a COP with major advances,’ he adds.

With regard to the EU's possible leadership at this summit - which Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, will not be attending- Valladares is sceptical: ‘The European Union has made some good cuts to the law on ecological restoration or renaturalisation, within which there was a very powerful framework for climate change’. As factors hindering further ambition, the scientist cites the far right, populism, instability and volatility of European politics. ‘It is going to be very difficult for Europe to have leadership on this issue,’ he says.

Is it still possible to meet the goal of limiting the temperature increase to below 1.5°C?

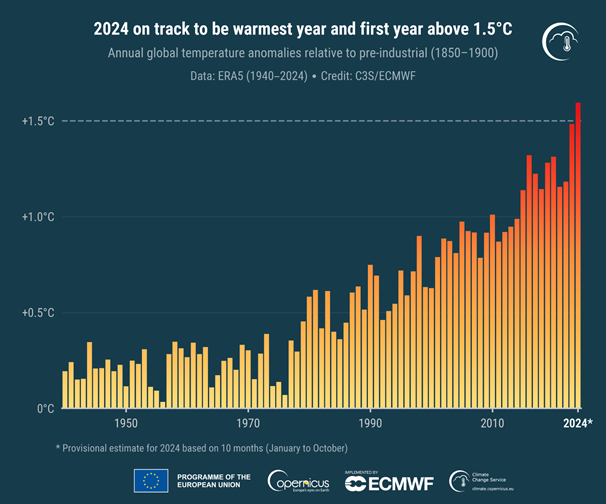

On current trends, data and projections suggest that this limit will be exceeded. Based on data from January to October 2024, it is ‘virtually certain’ that this year's average temperature will, for the first time, be more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service. This data will almost certainly make 2024 the warmest year on record. ‘The average temperature anomaly for the remainder of 2024 would have to fall close to zero for 2024 not to be the warmest year on record,’ the statement said.

In terms of projections, just a few days ago, the Emissions Gap Report 2024, published by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), pointed out that if countries do not submit more ambitious national contribution plans, the world is heading towards a temperature increase of between 2.6 and 3.1°C this century.

According to the report, emission reductions of 42% by 2030 and 57% by 2035 are needed to reach the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. ‘From a technical point of view, it is still possible to limit the global average temperature increase to 1.5°C,’ the authors argue.

Solar, wind and forest-based measures promise rapid and radical emission reductions. But to realise this potential, sufficiently robust NDCs would need to be backed by a governmental approach, measures that maximise socio-economic and environmental benefits, greater international collaboration including reform of the global financial architecture, strong private sector action and at least a six-fold increase in mitigation investment. ‘G20 countries, in particular the members with the highest emissions, would have to do the heavy lifting,’ the paper argues.