In the early days of August 2003, a heatwave occurred in Europe with temperatures far above those considered normal for the 1961-1990 period, which was the meteorological reference period at that time. Specifically, in Spain, Portugal, and southern France, these temperatures were between 7.5°C and 12.5°C above average. The high temperatures quickly resulted in an estimated excess mortality of 6,500 deaths in Spain, 14,800 in France, and around 70,000 across Europe, especially among those over 65 years old.

The heatwave of 2003 changed everything

This excess mortality and the lack of preventive measures had immediate political repercussions. In some countries, like France, it led to the immediate resignation of the French Health Director. In other countries, like Spain, it led to the meeting of Health Minister Ana Pastor with the two groups of experts who were working on the health-related impacts of heatwaves at that time. The directive was clear: the implementation of a High-Temperature Prevention Plan that should enter into force by the summer of 2004.

The few existing studies in Spain and Portugal on the impacts of heatwaves on mortality in the cities of Lisbon, Seville, and Madrid seemed to indicate that the daily maximum temperatures from which mortality increased were 34°C in Lisbon, 41°C in Seville, and 36°C in Madrid. These temperatures roughly corresponded to the 95th percentile (P95) of the series of daily maximum temperatures for the summer months (June-September) in those cities. This criterion was adopted for the implementation of the first High-Temperature Prevention Plan in 2004. A heatwave was defined, and the High-Temperature Plan was activated, when the daily maximum temperature exceeded the 95th percentile of the series of daily maximum temperatures from June to September, with the Ministry of Health adding that the 95th percentile of daily minimum temperatures must also be exceeded simultaneously. In other words, these were purely climatological heatwave definition thresholds.

Health Minister Ana Pastor met with the two groups of experts working on the impacts of heatwaves on health. The directive was clear: the implementation of a High-Temperature Prevention Plan to be in effect by the summer of 2004

Since that year, various research conducted in Spain, specifically in Castilla-La Mancha, which resulted in numerous international publications and two doctoral theses, revealed that defining a heatwave based solely on climatological values was not correct. Local factors such as population demographics, income levels, rural or urban character, healthcare system, infrastructure, etc., clearly influence the temperature from which heat-related mortality begins to increase.

Heat awareness campaign made by the Ministry of Health in 2007.

Avoiding heat-related deaths without issuing unnecessary warnings

In some cases, these heatwave definition temperatures, determined as those daily maximum temperatures from which mortality increases in a statistically significant way, corresponded to percentiles below 95, and in other places, above. In the first case, if this 95th percentile is assumed as the heatwave definition when it is actually lower, alerts would not be given when they should be, and thus possible heat-related deaths would not be prevented. Conversely, if the percentile corresponding to the heatwave definition is above 95 and this P95 is assumed as the heatwave definition criterion, alerts would be given when they are not necessary. Therefore, it is necessary to determine for each location what the heatwave definition temperature is to both prevent deaths and improve management.

With this goal, in 2015, the Carlos III Health Institute (ISCIII) determined, at the provincial level and for all of Spain, what the heatwave definition temperatures are and their associated health impacts for the period 2000-2009. For the first time, this makes it possible to have an estimate of the mortality associated with heatwaves in Spain, a value that is around 1,300 deaths/year for the aforementioned period. The Ministry of Health adopted these thresholds as the heatwave definition thresholds for its High-Temperature Prevention Plan, replacing the values that were in effect since 2004.

Heatwave prevention must be based on the temperature-mortality relationship, as in Spain, and made at the smallest geographic scale possible

On the other hand, evidence indicates that using provincial-level heatwave definition temperatures is an improvable approach, as different regions within the same province exhibit different climatological behaviors. Therefore, the WHO, regarding heatwave prevention plans, states that these should be made according to epidemiological studies based on the temperature-mortality relationship, as is the case in Spain, and at the smallest geographic scale possible.

Following these principles, the ISCIII has recalculated the heatwave definition temperatures in 182 regions with the same climatic behavior in Spain (the so-called “isoclimatic zones”). This shifts the work from using 52 meteorological observatories at the provincial level under the old High-Temperature Plan to over 1,100 observatories, using the average daily maximum temperatures recorded at all observatories within each isoclimatic zone and the daily mortality of all municipalities in that zone. These calculated temperatures are the basis of the 2024 High-Temperature Plan.

In 52.5% of the places, these temperatures correspond to percentiles below the meteorological P95 and coincide with this P95 in 30.7% of the cases.

The heat culture reduces the amount of deaths

Although it is clear that the Spain of 2004 in terms of the healthcare system, infrastructure, income levels, urban planning, housing quality, and social improvements, among other aspects, is very different from the current Spain, it is also clear that the impact of heatwaves on mortality has drastically decreased. Since 2004, with the implementation of the Prevention Plans, the population has become aware that heat can kill the most vulnerable people. Numerous campaigns on the impact of high temperatures on health, as well as the activation of numerous preventive measures in social services, nursing homes, and hospitals, have created the so-called "heat culture." This term was coined in the United States by Jennifer Bobb in 2014 regarding heat adaptation in that country.

If, for each degree that exceeded the heatwave definition temperature before 2004, mortality in Spain increased by an average of 14 %, after 2004, it barely exceeded 2 %

However, this adaptation to heat has not occurred only in the United States; Spain has also seen a drastic reduction in the impact of heat on mortality before and after 2004. If, for each degree that exceeded the heatwave definition temperature before that year, mortality in Spain increased by an average of 14%, after 2004, it barely exceeded 2%. This has been especially evident among the age group over 65.

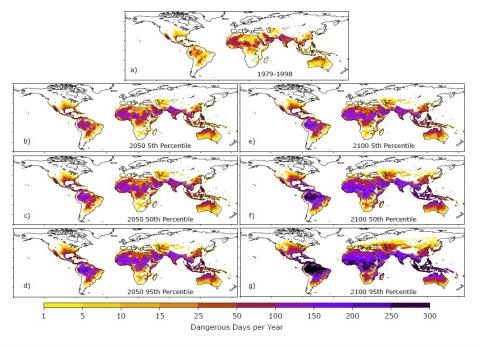

Therefore, it seems that, although temperatures continue to rise due to climate change, the adaptation to these extreme temperatures is limiting their impact. Despite this, particularly hot summers like that of 2022 had a very high heatwave-attributable mortality, established at over 4,800 people according to the Mortality Monitoring System (MoMo). Remember that studies for Spain indicate that, without adaptation, the annual heat-attributable mortality in an unfavorable emissions scenario by 2051-2100 would be around 12,000 deaths/year, but with complete heat adaptation, this figure would be around 1,000 annual deaths. The need for adaptation to high temperatures is therefore clear, and the Prevention Plan has proven to be a useful tool for this purpose.