Footprints of coexistence of different hominids described in Kenya 1.5 million years ago

At least two hominin species - Homoerectus and Paranthropus boisei- coexisted in Kenya's Turkana Basin around 1.5 million years ago, a study published in Science confirms. The authors describe the first physical evidence of this coexistence in the form of footprints, found at several sites in the area.

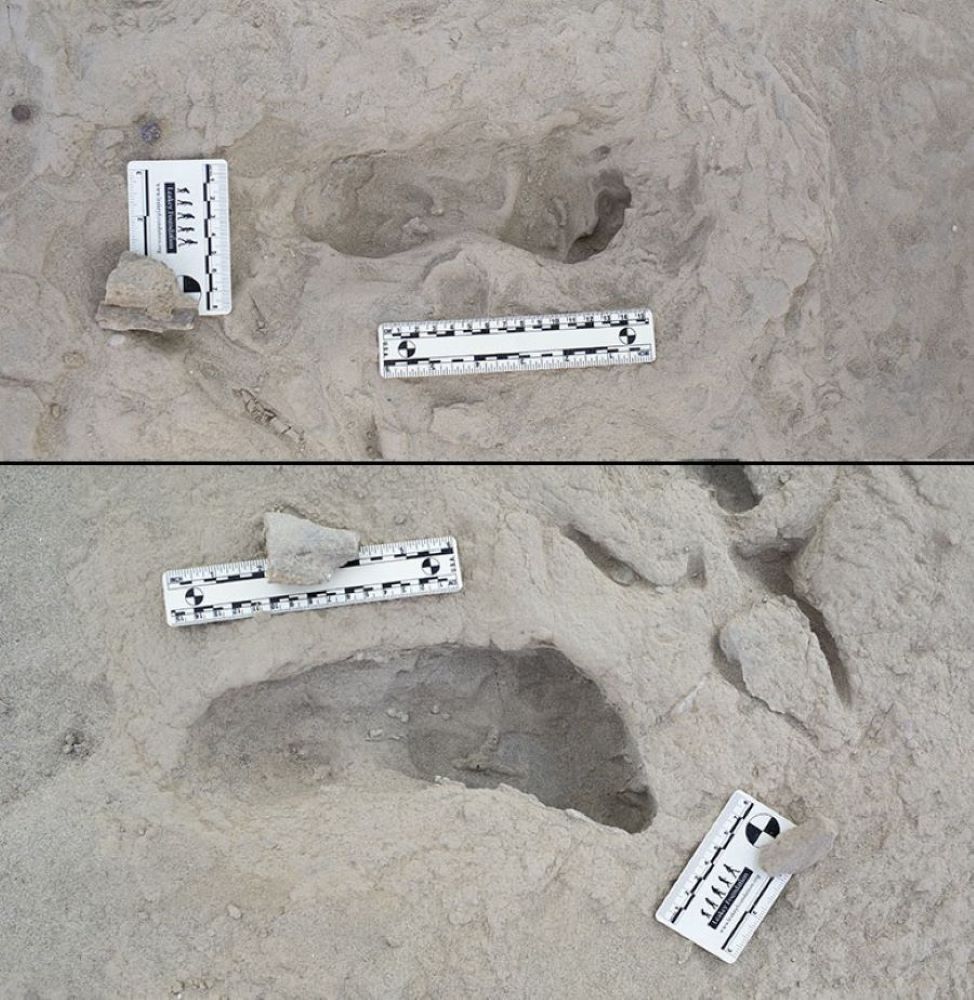

In this montage, the photograph on the left would correspond to a footprint created by a Homo erectus individual, while the one on the right would be the footprint created by a Paranthropus boisei individual. Credit: Kevin Hatala/Chatham University.

Juan Luis Arsuaga - huellas Kenia EN

Juan Luis Arsuaga

Palaeontologist and scientific director of the Museum of Human Evolution in Burgos

I find the article very interesting in two different aspects. It demonstrates the sympatry of two species of hominins (presumably Paranthropus boisei and Homo erectus) and indicates that one of them (P. boisei) had a more mobile and divergent big toe (i.e. a more primitive and less efficient bipedalism) than the other (H. erectus, better designed for long distance walking and running). I will explain it to my students in class! This paper represents a big step forward.

Gema Chacón - huellas Kenia EN

M. Gema Chacón

Researcher at IPHES-CERCA in Tarragona, associate professor at the Universitat Rovira i Virgili and associate researcher at the Muséum National d 'Histoire Naturelle (Paris, France)

The paper by Hatala et al. makes a significant contribution to the field of palaeoanthropology by providing direct evidence for the coexistence of different hominin species in the Early Pleistocene, a phenomenon that had hitherto been inferred only from scattered fossil data. The study's findings are based on detailed analyses of fossilised footprints from the FE22 site at Koobi Fora, Kenya, supported by robust methods including comparison with other sets of footprints of similar age, modern humans and chimpanzees. The identification of two distinct patterns of bipedalism attributable to Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei suggests broader locomotor diversity than previously thought, opening new insights into ecological interactions between these species.

This work aligns with previous studies on hominin diversity in the Pleistocene, but brings the novelty of documenting divergent locomotor patterns on the same footprint surface. This finding suggests not only the coexistence of these species, but also the possibility of differentiated ecological strategies that allowed them to share the same lake habitat.

In terms of implications, this work underlines the importance of considering behavioural and locomotor diversity in models of human evolution. Differences in bipedalism could reflect specific ecological adaptations, potentially reducing direct competition and favouring coexistence. These results invite future research that combines the analysis of fossilised footprints with other lines of evidence, such as human fossils and archaeological materials, to understand more comprehensively how ecological and behavioural dynamics influenced Pleistocene evolutionary processes.

Ana Marín - huellas Kenia EN

Ana B. Marín Arroyo

Full Professor of Prehistory and Director of the EvoAdapta Group at the University of Cantabria

The study of hominin footprints found in Kenya provides a unique window into the earliest stages of human evolution. Evidence of sympatric speciation and differences in foot biomechanics found at this site, called FE-22, suggest that the evolutionary history of hominins is much more complex than we thought.

This work provides the exceptional discovery of footprints made by two hominids with different foot kinematics at a very specific time and place and which are not often found in such ancient fossil contexts.

The study of these footprints has led researchers to propose that they are the footprints of two different hominins: Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei. This finding provides, for the first time, direct evidence of two hominin taxa coexisting and potentially interacting with each other in environments outside Lake Turkana during 1.5 million years ago, something that we could assume, but that with the time scales we use we could not determine if they really occurred in the same space-time.

The conclusions of the study are well supported by the different material evidence that not only includes the analysis of the hominin footprints, but also the fossil remains of hominids found in the surrounding area, the detailed geological study of the site and footprints of other animals, such as birds and bovids, which offer relevant information about the ecosystems that these hominids inhabited and exploited for their subsistence.

Future research, including the discovery and analysis of other sites with new tracks, as well as a better understanding of the environmental context and intraspecific variation, will help to answer open questions about the interactions between early Pleistocene hominins.

Adrián Pablos - huellas Kenia EN

Adrián Pablos

Lecturer of Palaeontology at the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM) and affiliated researcher at CENIEH

Kevin Hatala and co-workers have found a series of undoubtedly human footprints with bipedal locomotion, together with faunal tracks at the edge of a palaeolake with a chronology of about 1.5 million years. There is at least a trail of more than ten footprints and other isolated tracks.

The main novelty of this article (apart from the fact that they are hitherto unknown tracks) is that two different kinetic patterns of bipedalism can be observed among these tracks. That is, two different ways of stepping. Both are bipedal with the adducted big toe typical of bipedalism and different from the chimpanzee footprint. This leads them to consider that they may belong to two different taxa with different footfall biomechanics. They compare with other footprints from the African fossil record of similar chronology and observe that there are also two footprint patterns in different sites. But this would be the first time that both patterns have been observed at the same site.

Here comes the biggest limitation when studying footprints in archaeological sites: it is to know who made those footprints. In this case, at least two taxa of humans or hominins (H. ergaster/erectus and Paranthropus boisei) are represented in East Africa. Homo ergaster is a larger-bodied species than paranthropes, which resemble australopithecines in body size. Both population groups inhabit the region in these chronologies. The kinematic and size study of the footprints from this site of the KBS member allows them to possibly be associated with these two groups. When one looks at the fossil record of Homo erectus and Paranthropus boisei from the region in these chronologies, it is interesting to note that there are also two different morphologies in the different bones of the foot. Thus, at Koobi Fora, around a lake 1.5 million years ago, we have two types of footprints (in terms of kinetics/biomechanics of the footprint and in terms of overall size). In the same region there are at least two different hominin foot morphologies corresponding to a large-bodied species (H. erectus) and a small-bodied species (P. boisei). Most likely then, both types of footprints are made by these two types of hominins, indicating that both human groups coexist with slightly different ecological and environmental requirements. The authors propose at this point a possible low ecological competitiveness between Paranthropus boisei and Homo erectus.

Kevin G. Hatala et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed