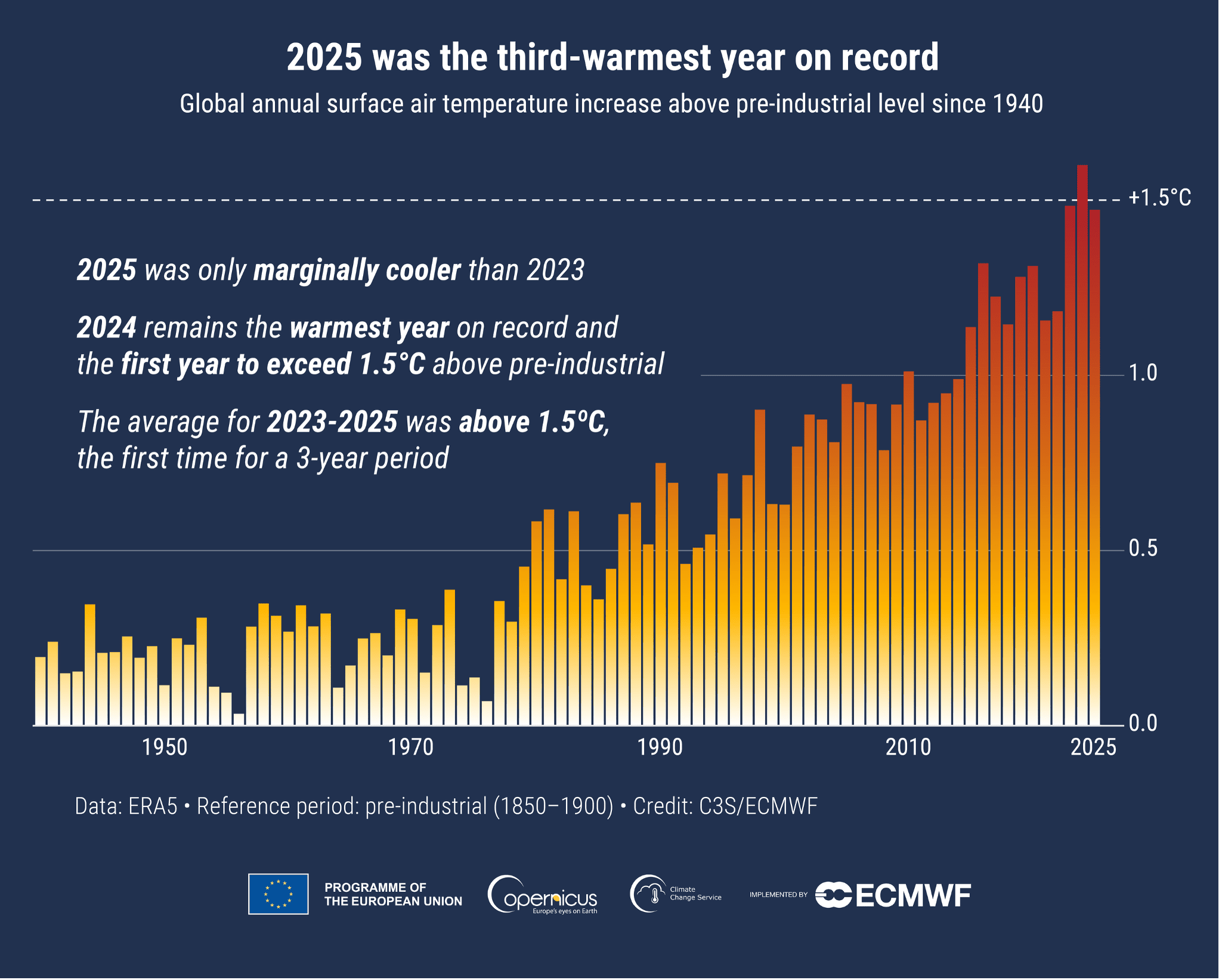

2025 was the third warmest year on record

According to data published by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), which manages the Copernicus Climate Change Service, last year was the third warmest on record. Globally, the last 11 years have been the 11 warmest since records began, and global temperatures for the last three years (2023-2025) have exceeded, on average, 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (1850-1900). This is the first time a three-year period has surpassed the 1.5°C threshold.

Global surface air temperature increase (°C) above the average for the pre-industrial reference period designated 1850-1900, based on the ERA5 dataset, shown as annual averages since 1940. Credit: C3S/ECMWF.

Rodó - Copernicus

Xavier Rodó

ICREA research professor and head of ISGlobal's Climate and Health programme

"The report reflects, as is unfortunately becoming the norm, that our planet is showing clear and evident signs of accelerating climate change. The indicators are numerous and, unfortunately, consistent, with no contradictory values. Therefore, the report's importance lies not so much in a single value, but in the synergy of many aligned indicators.

Copernicus is currently, and due to the discontinuation of many programs at NOAA (the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), the best tool the world has to objectively and scientifically warn of global and regional climate change. Its reliability is extremely high, both because of the methodologies applied and the academic and scientific institutions in charge of the program at the ECMWF.

How does this fit with the evidence already known, and what implications might it have?

"Unfortunately, too well." For several years now, all indicators have aligned to show that we are immersed in a spiral of global warming, whose global, regional, and local effects we are only beginning to understand. In fact, the fact that 2025 is the third warmest year on record is merely anecdotal, especially considering that it was only 0.1 degrees Celsius cooler than the second warmest (2023), and because both that year and 2024 (the warmest by 0.13 degrees Celsius) saw a strong El Niño event. Conversely, in 2025 we experienced cool conditions in the surface waters of the Pacific Ocean corresponding to a La Niña event, which we know produces a relative, but temporary, cooling effect on the climate. Without that, this year would clearly have been the warmest or the second warmest, without a doubt.

The fact that the 1.5°C threshold set by the Paris Agreement has been exceeded on average every three years for the first time is bad news, not so much because of the value itself, since it is an approximate limit, but because of the clear upward trend it indicates. Furthermore, the joint observation of sea ice covariation at both poles is highly relevant in itself.

The coming years, and particularly the next decade, will be crucial for a clearer understanding of the true value of global climate sensitivity—that is, the degree of warming per unit of CO2 emitted. Consequently, we will also gain a better understanding of the types of responses that will occur at the level of the different compartments of the climate system, both individually and in cascade, and we will have a clearer view of the impacts and effects of these changes on the planetary climate.”

Are there any significant limitations to consider?

“Given that this is the best available data, obtained with the best monitoring systems on the planet, we must acknowledge that, although the conclusions that can be drawn are always subject to a margin of error and uncertainty (we can never sample the planet 'perfectly'), right now it constitutes extremely reliable data on the state of the climate and its changes.”

Resco - Copernicus 25

Víctor Resco de Dios

Lecturer of Forestry Engineering and Global Change, University of Lleida

Climate change is accelerating. The rate at which temperatures rise year after year is increasing. Data confirms that global warming has already exceeded 1.5°C, as climate models predicted. The heat of 2023 and 2024 was caused by El Niño, whose effect faded in 2025 and resulted in a 0.1°C decrease in the 2025 temperature (compared to 2024). Some models indicate that El Niño could return from the second half of 2026, which would catalyze a foreseeable increase of 1.7°C in 2027. There are uncertainties about this prediction for 2027, since the 'official' models believe that the temperature rise will not be so abrupt.

Within this scenario, and amidst a brutal anthropogenic climate change whose intensity we are noticing summer after summer, we find a report that tends towards catastrophism and confuses the direct effects of climate on the Earth system with the indirect ones. The clearest example is when it discusses wildfires, whose occurrence depends on the interaction between climate, urbanization (living in 'flammable' areas), and preventative forestry activity: the surge in fire activity is not solely attributable to climate change. Furthermore, in the case of wildfires, the report claims that Europe experienced record emissions from fires in 2025, something that is only true on a very short timescale (20 years). This clarification is important because the text uses the pre-industrial period (1850-1900) as a reference point when discussing climate and should clarify that, in the section on wildfires, it refers to a much shorter time frame.

Beyond these inaccuracies, we must remember that climate change is increasingly becoming a matter of public health and civil protection, with significant impacts on sectors such as tourism, agriculture, and transportation, to name just three. We must also remember that, while mitigating climate change depends on global geopolitics, adapting to climate change does depend on us: we can do much to protect ourselves from the worst consequences of the looming climate change.

The temperatures of the summer of 2025 were undoubtedly extreme. But they will likely be benign conditions compared to those expected in 2040 or 2050.