Reactions to the wave of wildfires in the Iberian Peninsula

Coinciding with the heat wave, numerous wildfires have started and spread in the Iberian Peninsula, with two fatalities in the province of Zamora.

Incendio en el Parque Nacional de Monfragüe, en el municipio de Deleitosa (Cáceres). / Ismael Herrero | EFE

Cristina Santín - ola de incendios EN

Cristina Santín Nuño

Senior scientist at the CSIC and head of the Department of Biodiversity and Global Change of the Joint Institute for Biodiversity Research (University of Oviedo-CSIC)

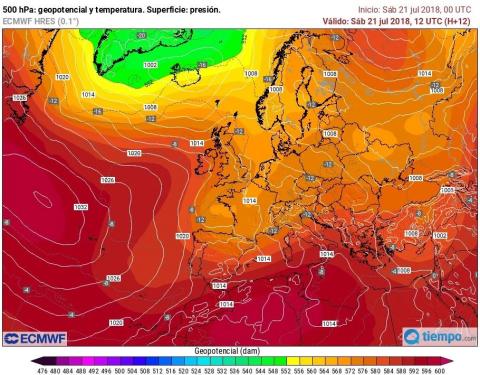

Under such extreme weather conditions of heat, dryness and, in some cases, more wind, it is easier for fires to become more virulent: faster, more intense and, therefore, more dangerous and difficult to control.

For a fire to start, we need three ingredients: something to start it (ignition source), vegetation to feed it, and weather conditions that make the vegetation dry enough to burn. Heat waves facilitate this third ingredient. In addition, these heat waves often involve thunderstorms which, when not accompanied by rain, are important ignition sources.

Fortunately, it seems that this heat wave is now subsiding, so hopefully the fire situation will improve as well. What happens for the rest of the summer will depend on how many more heat waves come. We've had three already and we haven't even finished July.

Climate change has already increased the meteorological risk of fires around the world. For example, in the Mediterranean basin, the extreme fire weather risk (associated with heat waves like the ones we are experiencing) has doubled in the last 40 years. Moreover, the fire season has now been extended by almost a month. This means that climate change is facilitating more and more severe fires. But it is not just a question of climate change; rural abandonment in our country is leading to more vegetation in our landscape and more continuous vegetation. It is the combination of more vegetation and more heat that triggers disastrous situations like the ones we are seeing now.

As for the sources of ignition, the natural origin is always lightning and, in some areas of Spain, this cause is quite frequent. But in many regions of our country, most fires are of human origin, either by accident or negligence or by arson caused by arsonists. It is essential to understand these causes and try to limit them as much as possible. For example, by prohibiting certain outdoor activities when the risk of fire is extreme (e.g. barbecues or working with spark-generating machinery). In the case of arson, it is a very complex issue. People always talk about increasing the legal penalties but that cannot be the only solution because proving that someone was at fault in the first place is extremely difficult. In my opinion, we have to work with and from the rural population to try to solve it.

Adrián Regos - ola de incendios EN

Adrián Regos Sanz

'Ramón y Cajal' postdoctoral researcher at the Biologial Mission of Galicia and head of the ECOP research group – Landscape Ecology

For yet another year, and in the middle of the heat wave, we feel the impotence of seeing our most emblematic forests and natural spaces burning with few realistic options for dealing with them. And what is the reason for this recurring situation? The problem is not a recent one, it has been going on for a long time. In Spain, as in many southern European countries, rural abandonment and the consequent loss of traditional agro-pastoral activity has favoured the transition towards more flammable landscapes. The amount of 'fuel', i.e. vegetation available to burn, has increased in recent decades. The abandonment that our rural world has been suffering since the middle of the last century not only entails a greater risk of fire but also the progressive loss of the great cultural value associated with these traditional activities, as well as an irreparable loss of biodiversity -many species are adapted to the habitats created by extensive agriculture and livestock farming in our country-. A large part of our grasslands, heathlands and wetlands have been progressively replaced by forestry plantations, whose planning responds exclusively to economic interests and whose management is conspicuous by its absence.

But the increase in the intensity and severity of the fires we have been suffering over the last decade is not only due to this variable. It is its interaction with other factors that makes this complex equation a difficult problem to solve. Current firefighting policies are focused on the immediate suppression of any type of fire, regardless of the conditions and intensity with which it occurs. This policy is paradoxically favouring the accumulation of 'fuel' by depriving our ecosystems of a fundamental ecological process, fire. How to manage our forest landscapes without fire, where are the resources for landscape-scale management to cope with this new generation of fires? They are here to stay and we need to be aware that global warming will only favour the conditions for these waves of fires to recur with greater frequency and virulence. The progressive accumulation of unmanaged vegetation, under the conditions of drought and water stress to which they are exposed, creates the ideal conditions for the generation of extreme events against which fire brigades have little to do beyond risking their lives.

We need to be aware of the problem. We need to create landscapes that are more resistant and resilient to large wildfires, to move towards 'fire-smart' territories. Our landscapes need proactive, adaptive and holistic management to enable rural development that is compatible - in the medium and long term - with biodiversity and ecosystem services. This requires a conciliatory, integrative and holistic approach that favours synergies between different sectoral policies and reduces the risks associated with climate change and rural abandonment in our country. The European Green Pact offers the regulatory framework to address these challenges, and undoubtedly a unique opportunity to integrate a 'fire-smart' vision in the new energy, environmental and agroforestry policies.

Cristina del Rocío - ola de incendios EN

Cristina Montiel Molina

Professor of Regional Geographical Analysis and Director of the Research Group 'Forest Geography, Policy and Socioeconomics'

Heat waves and large fires have always existed, but heat waves have not been so frequent and fires have not been so intense and disproportionate. These are no longer one-off extreme weather events. Climate change causes more intense heatwaves at unusual times and places. And the characteristics of today's landscape also lead to different fires, which are faster, more violent and completely beyond extinguishing capacity.

Since the middle of the last century, the fire regime has been changing rapidly (frequency, intensity and average area) but, above all, the socio-spatial context in which fires now occur is changing (simultaneity, uncertainty and vulnerability of the population). The "pyrotransition" or abrupt change in fire behaviour was a consequence of the destabilisation of the landscape due to the replacement of plant fuel (firewood) by fossil fuel (oil derivatives), which accompanied urban growth and the country's industrialisation process. Climate change has brought about new risk conditions. The problem we face today is different and requires different policies.