Mouse with two male progenitors to reach adulthood created

A team of researchers has used embryonic stem cell engineering to create a bipaternal mouse - a mouse with two male parents - that lived to adulthood. Their results, published in the journal Cell Stem Cell, show how targeting a particular set of genes involved in reproduction enabled this breakthrough in unisexual reproduction in mammals.

Lluís Montoliu - ratones 2 padres EN

Lluís Montoliu

Research professor at the National Biotechnology Centre (CNB-CSIC) and at the CIBERER-ISCIII

In early March 2023, at the Francis Crick Research Center in London, during the Third International Summit on Human Gene Editing, a Japanese researcher, Katsuhiko Hayashi, left the audience gasping and breathless when he told how he had succeeded in generating mice with only paternal contribution. Indeed, this scientist had discovered a complex and very sophisticated procedure to convert male pluripotent (embryonic or inducible) stem cells into female ones. In short, Hayashi took advantage of a very rare event that occurred when maintaining these cells in culture (the spontaneous loss of the Y chromosome) to rescue these cells and experimentally promote the duplication of the X chromosome. In this way, he was able to convert a male stem cell (XY) into a female stem cell (XX). And from the latter, he proceeded to differentiate them into ovarian cells in order to obtain eggs (which came from male cells!). These eggs could be used for in vitro fertilization (IVF) with sperm from another male mouse to obtain embryos, which gestate in a female mouse and give rise to apparently normal, fertile baby mice, whose father and mother are two male mice. These surprising results were published in Nature a few weeks later. And they even opened the door to obtaining mice whose father and mother were the same individual, a male mouse, who would normally provide sperm and eggs obtained from, for example, cells from his skin, to obtain embryos by IVF, taking advantage of the fact that mice naturally withstand the maximum inbreeding that this procedure would imply.

Almost two years later, a team of Chinese researchers, led by Zhi-kun Li, Wei Li and Qi Zhou of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has once again blown us away with an analogous procedure to obtain mice from two male mice. Qi Zhou is a researcher who has led many spectacular advances in assisted reproduction, transgenesis, cloning and gene editing procedures in mice and non-human primates. However, these researchers have opted for a totally different route to reach the same result: to get two male mice to be the progenitors of a baby mouse, produced without maternal biological intervention, beyond still needing a female mouse to gestate the embryos thus generated. The result was published in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

This new procedure developed by Li and collaborators is as sophisticated, if not more so, as the previous one designed by Hayashi. In this case, the researchers aim to combat one of the barriers to obtaining viable mammalian embryos by combining two gametes of the same sex (two sperm or two eggs). These embryos do not survive naturally, since mammals have a control system called genomic imprinting that requires that all embryos derive from a male gamete (sperm) and a female gamete (egg) for the simple reason that there are genes in our genome that only function if they are inherited from the mother and other genes that are only expressed if they are inherited from the father. And all of them are essential for survival.

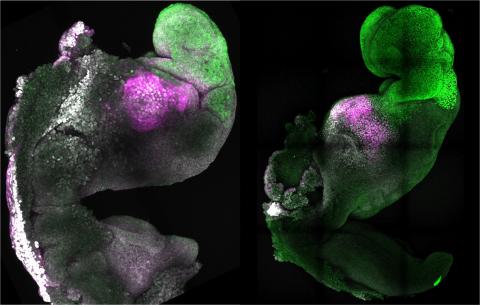

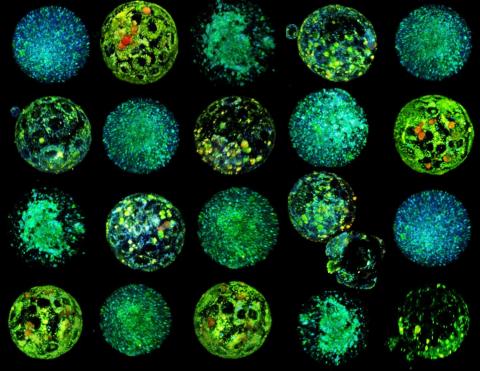

The highly complex protocol designed by these researchers begins by injecting a spermatozoon into an enucleated egg (without genetic material), inducing its initial development into blastocysts with only half of the necessary genetic material. This allows obtaining embryonic pluripotent cells called haploid cells (they only have half of the genome, they lack the maternal genome) and androgenetic cells (derived from sperm). These cells thus obtained are cultured long enough to excise, thanks to the use of CRISPR gene editing tools, the regions of the genome subject to genomic imprinting (in no less than twenty places of the genome). They thus eliminate this control mechanism that mammals have. Finally, one of these edited androgenetic haploid cells is injected into another enucleated egg along with another normal sperm. The injected cell plays the “maternal” role (although they are derived from sperm) and the new injected sperm plays the “paternal” role. They take this embryo back to the blastocyst stage and again obtain pluripotent embryonic cells (now already biparental), which they finally inject into another tetraploid blastocyst (obtained experimentally with four copies of the genome), which is commonly used in embryology to ensure the development of a placenta. This embryo is gestated by a mouse and the little mice that are born derive from two sperm, from two parents, without the genetic participation of eggs, without a mother.

However, this procedure is not all successes. As the authors themselves recognize, the mice generated with this protocol are not fertile, and can only be reproduced by cloning. In addition, more than half of these biparental paternal mice do not survive, die early, do not mature properly and do not reach adulthood. The explanation for these problems probably derives from the CRISPR editing procedure used to eliminate the genomic imprint, which is very risky, is not performed optimally and generates unforeseen alterations. In a previous study, the same research team had shown that maternal biparental mice (two mothers, no father) were fertile and survived longer than paternal biparental mice (two fathers, no mother), which all died shortly after birth. In this new paper they have now published, they have improved these results, although still partially.

These are experimental studies carried out with mouse embryos, but what could be their significance and impact if these techniques ever improve so much that they can be safely used in the production of human embryos? If possible (which is not yet possible), they would promote a real revolution in assisted reproduction clinics. For example, homosexual male couples could both be the biological parents of their children. One of them would provide the sperm and the other member of the couple would provide pluripotent stem cells which, following either of the two procedures (that of the Japanese team or that of the Chinese team) would end up producing eggs that could be fertilized in vitro and gestated by a woman through surrogacy or surrogacy, something that is illegal in our country but is permitted in other countries. At present, if a male homosexual couple wants to have biological children, they must decide which of them will provide the sperm that will be used to fertilize an egg from a donor. At present, the children born are only biological to one of the two members of the couple.

Similarly, a female homosexual couple could also have biological children with the contribution of both women if one of them contributes eggs and the other contributes pluripotent stem cells that end up producing sperm (following the procedure developed by the Chinese team). Either of the two women could gestate the embryo thus obtained and the children born would belong to both of them.

And, if we let our imagination run wild, supposing (which is a lot to suppose) that we were able to overcome maximum inbreeding, which is viable in mice, but not in humans, both men and women, individually, as single-parent families, could have children whose genetic endowment would only come from themselves. A man could provide sperm, naturally, and from his skin cells end up deriving eggs that would be fertilized with his own sperm. The resulting embryo would be gestated by a woman and the child born would have the same man as father and mother. Similarly, a woman could provide eggs and, from her skin cells, end up developing sperm in the laboratory, which would be used to fertilize her own eggs. The resulting embryo could be gestated by herself and the child born would be fathered by the same woman.

For the moment all these applications in human assisted reproduction are still science fiction, because they are not yet technically possible and it would be imprudent to try to implement them. But, assuming that all these protocols will be optimized and that one day we will be able to consider whether or not we want to offer them in assisted reproduction clinics, I think it is important to reflect on this, to ask ourselves which of these techniques we would be willing, as a society, to accept ethically, to approve legally.

Li et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Animals