Temperature-related deaths could rise by 50% in Europe by the end of the century

An international team has analysed temperature and mortality data from 854 urban areas in Europe, and estimated that temperature-related deaths could increase by 50 % by the end of the century - which would mean up to 2.3 million more deaths - if no climate change mitigation measures are taken. This percentage is even higher in southern parts of the continent, such as Spain. The results are published in the journal Nature Medicine.

250127 muertes calor - víctor EN

Víctor Resco de Dios

Lecturer of Forestry Engineering and Global Change, University of Lleida

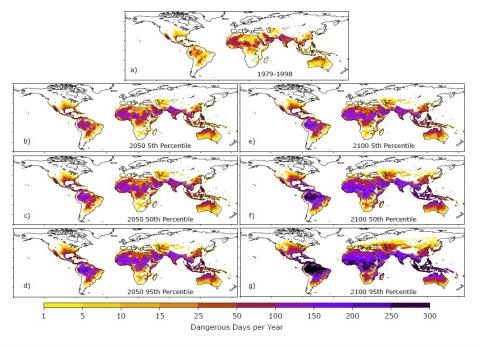

Over the last decades we have experienced heat waves, such as those of 2003 or 2022, when more than 60,000 people lost their lives in Europe. However, cold currently kills more people than heat. This new study shows how this trend would be reversed across Europe, with the sole exception of Scandinavia. That is, with climate change we will see an increase in heatwave-induced mortality and a decrease in cold-induced mortality, so that heatwave deaths will outnumber deaths by freezing. This trend will be particularly pronounced in southern Europe, and in Spain almost 1 in 3,000 people are expected to die from heat-related deaths annually by the end of the century.

The good news is that we can adapt. Adaptation starts with relatively simple - though not free - solutions, such as installing air conditioning or installing air-conditioned spaces that serve as climatic shelters (shopping centres, swimming pools, etc.). But we must also address more complex solutions, such as increasing green spaces in cities to mitigate the urban heat island, and adapting health systems to these epidemiological changes.

Nunes - Temperaturas (EN)

Raquel Nunes

Assistant Professor in Health and Environment at the University of Warwick Medical School (UK)

The findings of this study have serious implications for public health. As climate change leads to more extreme heat events, the number of heat-related deaths is expected to rise, putting additional pressure on healthcare systems. Vulnerable groups, such as older adults, those with chronic illnesses, and low-income communities, will be at the highest risk. Without strong adaptation measures, public health systems could struggle to cope with the increased demand for emergency services and hospital admissions.

To protect public health, governments and policymakers need to invest in early warning systems, public education campaigns, and infrastructure improvements to help individuals stay cool and safe. Health professionals must also be trained to recognise and respond to heat-related illnesses. Additionally, social policies that provide support for vulnerable populations, such as access to cooling centres and affordable healthcare, will be essential in reducing the impact of extreme temperatures.

This study highlights the urgent need for a coordinated public health response to climate change, focusing on prevention, preparedness, and adaptation to reduce future health risks. A significant proportion of current and future heat-related illnesses and deaths is preventable. What is essential now is the development and implementation of policies and actions aimed at minimising both morbidity and mortality.

Osborn . Temperaturas (EN)

Tim Osborn

Director of the Climatic Research Unit, University of East Anglia (UK)

Cold weather and hot weather kill tens of thousands of people across Europe every year. Climate change is bringing less severe cold weather but more frequent hot weather, but it isn't yet known if that means more or fewer people will die from temperature-related deaths in future. The clear finding of this new research is that the net effect of climate change will be more temperature-related deaths in future. Put bluntly, the increase in hot weather will kill more people than the decrease in cold weather will save.

While this new study isn't the final say on the matter, and more research will certainly refine and could still change the overall prediction of future temperature-related deaths, it does break new ground by scrutinizing people's vulnerability to extreme temperatures by age and by city to a much better level of detail than previous work. This extra level of detail ought to make the new study's results more reliable.

This study also confirms two more general features about climate change. First, the harm from climate change impacts people very unevenly (in this case, with far greater increases in temperature-related deaths predicted for southern Europe than for northern Europe, where milder winters may even reduce the number of deaths). Second, we can greatly reduce the harm from climate change by adaptation —making changes that increase our resilience to extreme weather— but these adaptations are far more successful if we also limit the amount of climate change that we are faced with by accelerating the move away from fossil fuels as our primary energy source.

Pierre Masselot et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- People

- Modelling