Reactions: two studies link microbiome changes to chronic fatigue syndrome

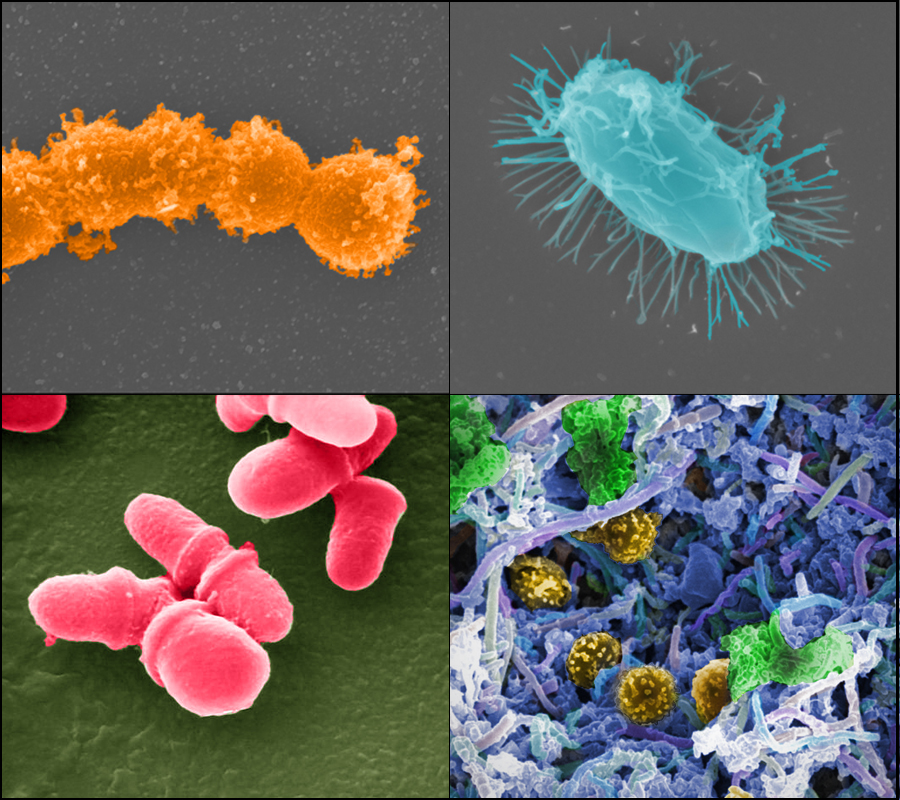

Two studies have found changes in the microbiome of patients affected by chronic fatigue syndrome. In particular, they have found a decrease in both butyrate and certain bacteria that produce butyrate. Butyrate is a factor related to the protection of the intestinal barrier and appears to play a role in the regulation of the immune system. Both papers are published in the journal Cell Host and Microbe.

Jordi Casademont - microbioma fibromialgia EN

Jordi Casademont

Director of the Internal Medicine Department and head of the Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Functional Unit at the Hospital Sant Pau in Barcelona

The study seems well conducted and can be considered of good quality. This is supported by the fact that it is published in a prestigious journal.

That said, there are several things to assess. While it is true that the patients show statistically significant differences, it is debatable whether these are clinically relevant. Is it relevant, for example, that a medication lowers systolic blood pressure by 0.05 mmHg, no matter how statistically significant the difference is because 10,000 patients were included? It is not. But the worst thing is that the dispersion of cases is almost the same in the two groups. In practice, what the authors find does not seem to lead anywhere beyond suggesting that this might be an avenue for further research.

On the other hand, studies of gut microbiota are very complex to analyse. After years of intensive research, we hardly have practical applications that can be used in the clinic. There are countless articles that associate microbiota patterns with specific pathologies. But for the time being it is not possible to go beyond mere description. Moreover, the findings are not always consistent between laboratories, even if we only take into account the studies of highest quality. These studies are, so to speak, far from standardised.

Gut microbiota is undoubtedly a very interesting field of study, but for the moment we could say that we are still in the phase of collecting information, not drawing conclusions. There are enormous variations between individuals, linked to many parameters that we hardly know, and it is risky to try to draw conclusions that are of practical use. The authors of these two articles themselves insist that the data do not imply causality, merely correlation. We can ask ourselves: could the differences between patients and groups be due to the fact that patients, because they are unwell, eat a slightly different diet: maybe they eat less meat and more vegetables, for example, or products with probiotics? By the same token, might they have consumed more antibiotics?

I think this paper does little more than encouraging further research in this field. It seems to be another article out of the dozens that are published every year, merely describing supposed alterations in patients with central sensitivity syndromes. I have been seeing articles along these lines for years, and very rarely do the same authors offer, after a few years, a body of work that builds on the initial findings to establish the aetiopathogenesis [causes and mechanisms] of these syndromes.

Having said this, let it be clear that this is a welcome study. It may turn out to be the one that will provide a better understanding of the pathogenesis of these diseases. We shall see. But I tend to be cautious, or even skeptical.

In any case, I don't think it has any short-term implications for patients.

Rosa del Campo - microbioma fibromialgia EN

Rosa del Campo

Researcher at the Ramón y Cajal Hospital and member of the Specialised Group for the Study of the Human Microbiota of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC-GEMBIOTA)

In both papers the authors study the specificities of the microbiota in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. This disease has no specific diagnostic criteria and it is sometimes a problem to label it correctly. It is partly related to fibromyalgia and is often lumped with it. So one of the main limitations is a correct diagnosis.

The two studies are of high scientific quality because of the number of patients recruited, the techniques used and the bioinformatic methods they have developed.

The study populations are different. The study by Guo et al. includes patients with irritable bowel symptoms (self-referred, so they do not have a secure diagnosis either) and patients without bowel symptoms. The study by Xiong et al. differentiates between patients with a short evolution of four years and those with a long evolution of ten years.

Both studies use healthy controls from the same environment and location. Both focus on the composition of the microbiota, but above all on its function, in particular by analysing short-chain fatty acids, which are metabolites exclusive to bacteria—humans do not have the capacity to synthesise them. What is most striking is that all patients have a lower concentration of butyrate and propionate in their faeces, which is blamed for the inflammation and low metabolism of these patients. There is also a striking deficiency of bacterial respiration.

This disease, or this set of diseases, has always had an onset of symptoms linked to a systemic viral infection, which most patients mention. This is supposed to trigger intestinal alterations (remember that some viruses are bacteriophages that could contribute to the balance of the intestinal ecosystem). In the study by Xiong et al. the authors comment that four years after the disease, the differences in the composition of the gut microbiota are much more pronounced than after ten years. This could be a sign of the ability of the microbiota to recover its initial diversity over time.

It is also important to differentiate between patients who report an irritable bowel and those who tend to be more constipated, as this could certainly indicate different microbiota scenarios.

The major novelty is that the authors demonstrate with solid conclusions that in the patients’ group, the production of butyrate is lowered and related to a lower amount of Faecalibacterium and Eubacterium. In view of these results, an intervention should be considered, either with external administration of butyrate or of the bacteria that produce it. Finally, these results provide indicators that we could measure to monitor the evolution of this disease, which so far hasn’t been associated with clinical measurements outside the normal range.

Both studies have taken into account the main limitations of this pathology, but as mentioned above, perhaps the most relevant is the lack of diagnostic criteria and the great variety of symptoms presented by patients, which prevents us from having uniform cohorts. On the other hand, the contribution of the microbiota to this pathology has long been suspected, but the human factor has yet to be established. Perhaps, like bacteria, human cells are respiration-deficient and metabolism is slowed down as a result. There is certainly still a lot to be discovered in this disease, but for the first time a different intestinal metabolism has been found in patients and healthy controls in relation to butyrate, which is already known to be a source of energy for the cells of the intestinal mucosa.

Joaquim Fernández Solà - microbioma fibromialgia EN

Joaquim Fernández Solà

Professor of Medicine at the University of Barcelona and coordinator of the Central Sensitisation Unit at the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona.

The two studies are novel and of high scientific interest, and have a high methodological quality, with the use of metabolomic and metagenomic techniques. They are published in a journal specialised in the microbiome, with high scientific impact.

These studies corroborate the line of research initiated some five years ago on the role of the microbiota in chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME). However, these studies are more systematised, carried out on larger samples and with better methodology than the previous ones. They not only make it possible to establish pathogenic correlations between the microbiota and CFS/ME, but also to determine the role of certain mediators, such as intestinal butyrate biosynthesis and the abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. They also profile specific microbiota phenotypes for increased fatigue intensity and for newly diagnosed versus long-standing CFS/ME subgroups.

These articles provide biomarkers that may be useful for assessing gastrointestinal involvement in CFS/ME patients. However, as the authors themselves state in the limitations of the studies, these are not diagnostic markers of disease, but of the process of gastrointestinal dysfunction. Nor do they immediately assume that they can act directly on the microbiota and improve the symptoms of CFS/ME. We are still in the early stages of scientific understanding of the microbiota and its mediating role in multiple diseases, including CFS/ME.

CFS/ME is a complex disease of neuroinflammatory pathogenesis with systemic repercussions. The microbiota interrelates with the brain in this disease, modulating intestinal reactivity to food and external factors and triggering local inflammatory reactions, with potential systemic repercussions. The more we know about the microbiota in CFS/ME, the better we will understand what happens in gut dysfunction in this disease. However, we must not forget that the main site where this dysfunction mainly occurs is in the central nervous system. What happens in the gut may only be secondary to the central nervous system alteration in the brain-gut axis.

Declares that he has no conflict of interest in the evaluation of these two articles.

Toni Gabaldón - microbioma fibromialgia EN

Toni Gabaldón

ICREA research professor and head of the Comparative Genomics group at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) and the Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC-CNS).

These two studies investigate changes in the faecal microbiome and blood plasma metabolome associated with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME). One is the first study to differentiate between recent illness (diagnosed within the last four years) and long-term illness (diagnosed more than ten years ago), providing insight into how disorders of the microbiome progress when the disease is established. The two studies are consistent in several respects, including the detection of a decrease in gut biodiversity and in the abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria, an anti-inflammatory metabolite with a known beneficial effect on the intestinal epithelium.

Both studies are of good quality and use high-resolution techniques - shotgun metagenomics, which looks at the whole genome, as opposed to previous studies based on 16S single gene analysis. The analyses are correct and use validated approaches. Both studies have their limitations, as the authors themselves acknowledge. One limitation is the small sample size, especially considering the heterogeneity of the symptoms of this syndrome. Also, such studies provide correlations, not cause-effect relationships, as the authors acknowledge, and further research is needed. For example, differences between the diets of different groups could explain some differences in the composition of the microbiota. However, the congruence between the two studies reinforces the validity of the suggested relationships.

These studies shed light on a syndrome whose causes are unknown. The study does not establish the causes, as we have said, but it allows us to establish some hypotheses on how it may become established in the long term through a disturbance of the intestinal balance that becomes chronic. I think we are still far from understanding this process. It is possible that the alterations detected are responsible for some of the symptoms of the disease, especially those related to digestive functions. And if so, interventions on the microbiome using probiotics, prebiotics or dietary changes could alleviate some of these symptoms, which would increase the quality of life of patients.

Another result included in both studies is the diagnostic potential that analysis of the faecal microbiome can have. Using artificial intelligence techniques, they detected microbial patterns that allowed them to distinguish between healthy people and patients with the syndrome. However, similar alterations have been detected in other syndromes (such as irritable bowel syndrome) and this study does not allow us to know whether the diagnosis would be specific to the syndrome studied or simply detect an unhealthy microbiome.

Xiong et al.

- Artículo de investigación

- Revisado por pares

- Estudio observacional

- Humanos

Guo et al.

- Artículo de investigación

- Revisado por pares

- Estudio observacional

- Humanos