Lithium pollution from Falcon 9 re-entry into the atmosphere measured for the first time

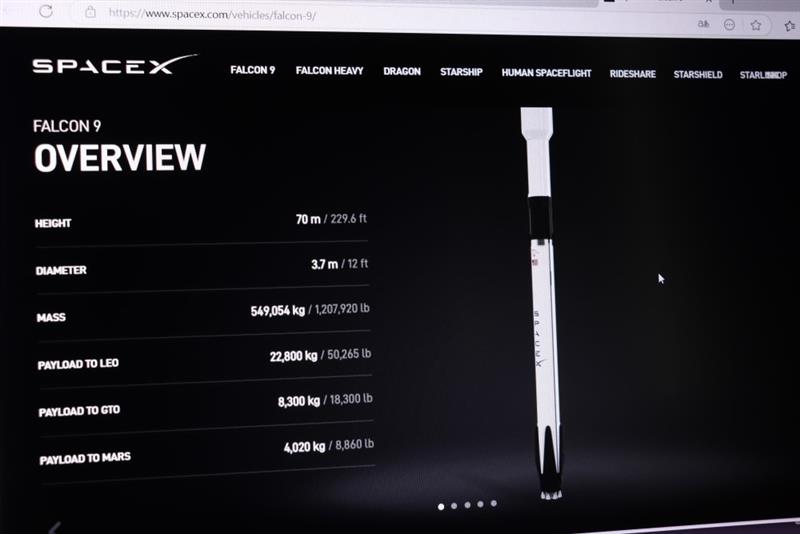

In February 2025, lithium concentrations suddenly increased around 96 km above sea level some 20 hours after a SpaceX Falcon 9 launch vehicle re-entered the atmosphere. This is the first direct detection of pollution in the upper atmosphere due to the re-entry of a spacecraft, according to a study published in Communications Earth & Environment. Lithium is used in spacecraft components, but it is only found naturally at these altitudes in trace amounts, and its accumulation could have consequences on the climate.

260219 litio falcon olga ES

Olga Zamora

Support astronomer at the Canary Islands Institute of Astrophysics

The study is based on direct laser measurements from the ground and advanced atmospheric models, so its methodology is robust and consistent with the current state of science. It is consistent with previous studies that had already detected metals re-entering the stratosphere and warned of the growing impact of space traffic, but it adds an important new element: this is the first time that a lithium plume from the re-entry of a Falcon 9 has been observed and tracked in time and altitude, demonstrating that pollution can be detected even at an altitude of around 100 km.

As a limitation, this is a single event and does not yet allow for an assessment of the cumulative impact on the climate or the ozone layer. In practice, the study is relevant because it shows that it is possible to monitor the atmospheric footprint of satellites and rockets, and suggests that, given the increase in re-entries, it is advisable to strengthen international monitoring, improve inventories of materials used and preventively assess their possible long-term environmental effects.

260219 litio falcon jorge EN

Jorge Hernández Bernal

Researcher in the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, Sorbonne Université, CNRS (France)

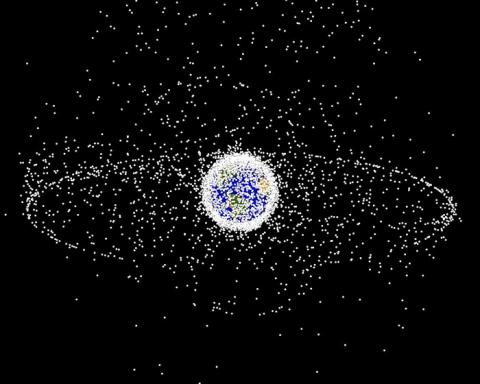

The space sector has been expanding rapidly in recent years and it has been projected that its growth could reach 9% annually over the next decade. In practice, this means that the number of satellites in orbit has tripled in the last five years and the number of launches has gone from the typical 100 per year in the past to 324 in 2025. This reality and these projections collide with another reality that, despite denialism, is becoming increasingly apparent: the climate, ecological and resource crisis.

Beyond the impacts inherent to any industry, the space sector has environmental impacts on the upper layers of the atmosphere that are not well characterised. Both rockets in ascent and the disintegration of satellites and other objects such as rocket trails release considerable amounts of gases and particles that remain in these upper layers of the atmosphere for a long time before finally falling. These pollutants contribute to climate change, but they also destroy the ozone layer and can alter natural processes, such as the formation of mesospheric clouds.

In this context, this study reports for the first time the direct observation of pollutants produced by the disintegration of space debris. What has been observed is a very high increase in the concentration of lithium at an altitude of about 100 km hours after the disintegration of rocket debris in the atmosphere. The authors focus on lithium because it is particularly easy to detect, but the important thing is that this “lithium cloud” must be associated with other pollutants produced during disintegration.

The interesting thing about this measurement is that it paves the way for further observations to help monitor the pollution produced by disintegrations in the upper atmosphere. The measurements were taken from Germany on a relatively exceptional occasion, because normally large objects (easier to observe) are intentionally and (more or less) controlled disintegrated in the Pacific Ocean, where the risk of fragments falling on populated areas is lower. In this case, the upper stage of the Falcon 9 rocket lost its manoeuvrability and ended up falling uncontrollably over Europe. In fact, at least one fragment ended up falling near a populated area in Poland.

Understanding and quantifying the environmental impacts of any human activity is important in order to transform our socio-economic systems, which are currently completely unsustainable and contrary to the general interest. In this sense, this new study is an interesting step forward. However, there is broad scientific consensus that the socio-economic transformations we need involve reducing inequality and rationalising the use of natural resources. The space sector, like other sectors, requires more international cooperation, more multilateralism, more development of international law and fewer speculators and opportunistic billionaires. In times of barbarism, we need courage and bold policies. The growth projected for the space sector is clearly unsustainable, but a rational use of space can bring many benefits to humanity as a whole and help us overcome the civilisational crisis we are entering.

260219 litio falcon 9 josé m EN

Jose María Madiedo Gil

Astrophysicist at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (IAA-CSIC)

This article describes the first direct detection of atmospheric pollution caused by the re-entry of space debris. The case occurred following the uncontrolled re-entry of a Falcon 9 rocket upper stage in February 2025. Approximately 20 hours after the event, a scientific laser (a lidar) located in Germany detected a cloud of lithium atoms at an altitude of 96 km, a region of the atmosphere where there are normally negligible amounts of this element. In fact, the concentration observed was ten times higher than usual.

The researchers reconstructed the trajectory of that air mass using atmospheric models and wind measurements. The result: it coincided with the rocket's route after traveling about 1,600 km from the Atlantic. In addition, they ruled out that this lithium-rich air mass was related to any natural phenomenon, such as geomagnetic storms or known ionospheric processes.

Lithium is a key element in this research because it rarely reaches the upper layers of the atmosphere naturally from meteorites, but it is present in materials that form part of rockets and artificial satellites. Therefore, detecting it acts as a ‘chemical signature’ of human origin.

This study demonstrates for the first time that the disintegration of spacecraft leaves measurable traces in the upper layers of the atmosphere, that this disintegration begins at an altitude of around 100 km, and that we can trace this pollution back to its source. This is highly relevant, as we are entering an era of satellite megaconstellations. This means that thousands of objects will re-enter the atmosphere each year, injecting metals into atmospheric layers that influence ozone, aerosols, and the planet's radiative balance. We do not yet know the total impact, but thanks to this study, we do know that the phenomenon is real and quantifiable. However, the results suggest that it would be advisable to have a network of lidar detectors similar to those used in this work to better quantify the effect of this type of pollution on the atmosphere.

260219 litio falcon 9 david EN

David Galadí-Enríquez

Lecturer in the Department of Physics at the University of Cordoba

The uncontrolled growth of artificial satellite fleets in low orbit means that all these objects, when they re-enter (and they all eventually do), vaporise and inject large amounts of metals into the atmosphere. These metals have either never been in the atmosphere (such as lithium, the subject of the article) or are there as a result of the natural flow of meteors, but in much smaller quantities than those induced by this human activity.

The article estimates that a single re-entry such as the one studied in this article adds almost 400 times the amount of lithium that falls naturally from space in a whole day to the atmosphere.

The article itself acknowledges that the anthropogenic accumulation of metals in the upper atmosphere has cumulative effects with potentially significant climatic consequences, and that clarifying the uncertainties involved requires observations and climatic and chemical modeling.

The relevant point is that all the studies needed to assess the climate impact of megaconstellations are being offloaded onto the scientific community without providing additional resources for this purpose, and that polluting companies can do so without being required, until now, to make even the slightest effort related to the consequences of their activities.

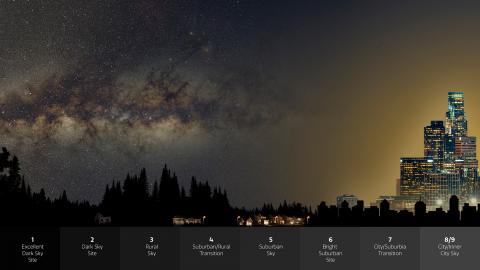

As in the case of classic light pollution (caused by ground lighting), satellite megaconstellations have an impact on astronomical observation, but their consequences go beyond that. Just as classic light pollution has effects on ecosystems and human health, the unlimited growth of satellite megaconstellations affects the global climate in ways that are not yet clear, via re-entries. In addition, this proliferation congests low Earth orbit and increases the risks to its use by increasing the probability of collisions with active or inactive objects (space debris).

Robin Wing et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed