What are CAR-T cells?

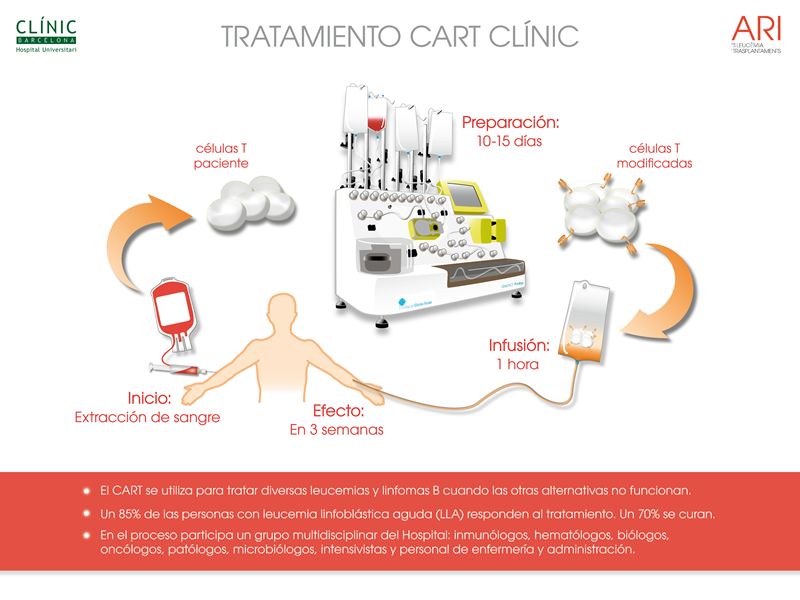

They are a type of cell modified in the laboratory to target and destroy other specific cells. Specifically, they are T lymphocytes—defense cells of the immune system—that are currently collected from the patient and then modified by adding a gene that produces what is known as a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). This receptor recognizes a specific protein present in the target cells and enables the CAR-T cells to attack them. Thus, it is a treatment combining immunotherapy and gene therapy.

What are they used for?

Currently, there are six approved commercial CAR-T cell therapies, all indicated for blood cancers such as multiple myeloma and certain B-cell lymphomas and leukemias. However, there is a lot of ongoing research and numerous clinical trials aiming to expand their indications. These targets include other blood cancers, solid tumors (in organs such as the lung, breast, or colon), or autoimmune diseases like lupus or multiple sclerosis.

What has happened with the FDA and EMA regarding these treatments?

On November 28, 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a statement informing that it had received reports of T-cell tumors in patients treated with various CAR-T cell therapies. As it was mentioned in the statement, " although the overall benefits of these products continue to outweigh their potential risks for their approved uses, FDA is investigating the identified risk of T cell malignancy with serious outcomes, including hospitalization and death, and is evaluating the need for regulatory action." In other words, there was a suspicion that these T-cells could be related to certain cancers.

In January 2024, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) also initiated an investigation. On June 14, it published the initial results.

What do the data show so far?

Although the FDA has not published specific information, two doctors working for the agency wrote an article about this in the journal NEJM. In January 2024, out of more than 27,000 people treated with CAR-T cells, 22 T-cell tumors had been diagnosed post-therapy. According to the authors, "the overall rate of T-cell tumors among people receiving CAR-T therapies appears to be quite low, even if all reported cases are assumed to be related to treatment."

Are not all cases related? How can we know?

CAR-T therapy is a type of gene therapy that introduces an external gene into cells. Although efforts are made to target specific and harmless genome locations, currently it could randomly integrate into a region that disrupts cell division, increasing the risk of cancer. Also, the chosen T cells might have a pre-existing mutation predisposing them to cancer, as these cells tend to multiply rapidly after modification, which could increase the risk. Ultimately, it is difficult to definitively determine if the therapy caused a tumor, but for the suspicion to be properly justified, it is to be assumed that the cancerous cells should have the gene of the artificial receptor in their genome. Its absence does not completely rule out the therapy's role, but " to explain it, other reasons are much more plausible," says to SMC Spain Manel Juan, head of the Immunology Service at Hospital Clínic de Barcelona and the joint Immunotherapy Platform with Hospital Sant Joan de Déu.

"Currently, patients receiving these therapies are at the last line of treatment: they have already undergone many cycles of chemotherapy, which increases the risk of developing secondary mutations not caused by CAR therapy itself," explains Juan. It is also proven that patients with B-cell tumors have a higher risk of developing T-cell malignancies inherently. Additionally, the statistics might partly reflect a survivor bias: secondary tumors are observed in those who survived thanks to the therapy. As an explanatory article stated, "to put it simply, one needs to be alive to be diagnosed with cancer."

Among the 22 cases collected by the FDA, and although many could not be studied in depth, the gene was confirmed present in only three of them.

The EMA's data, collected by the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee and published in June, includes around 42,500 patients treated with these therapies. Of them, 38 developed a T-cell tumor post-treatment. The gene's presence could be studied in half the cases, and it was confirmed in seven.

Besides the records from the two agencies, an article in the journal NEJM published also in June, included 724 patients treated with CAR-T therapies at Stanford University Medical Center since 2016. One of them developed a T-cell lymphoma without the gene being present. The tumor had pre-existing mutations, and although the authors do not rule out a possible contributing effect from both the therapy-related inflammation—something that, according to Juan, "has no clear scientific evidence"—and the chemotherapy itself, their main hypothesis is that: "Given that the baseline risk of developing a secondary T- cell tumor it is known to be higher in patients with prior B-cell lymphoma [as it was the case]; the T-cell tumors observed after CAR-T cell therapies, may reflect a circumstantial rather than a direct effect in a sufficiently large patient population."

More recently, a study published in the journal Clinical Cancer Research analyzed data from 1,253 patients included in four clinical trials. Their conclusions indicate that there are no differences in the overall risk of developing a secondary tumor if CAR-T therapy is used instead of standard treatment. The risk, in fact, primarily depends on the number of treatments previously administered.

What do experts say about the real risk?

Ignacio Melero, professor of Immunology at the University of Navarra, researcher at CIMA, and co-director of the Immunology and Immunotherapy department at the Clínica Universidad de Navarra, says, "the risk is not clearly quantified, but the estimate is less than one case per thousand treatments. Probably it is between one in a thousand and one in ten thousand. It is an effect we already feared would be observed when analyzing very long series of patients. For the diseases where CAR-Ts are currently indicated (leukemias, lymphomas, or myelomas), which are sometimes fatal within months, the benefit far outweighs the risk."

Manel Juan and Joaquín Martínez López, head of the Hematology Service at Hospital 12 de Octubre in Madrid, also believe that currently "the benefit is much greater than the risk." Additionally, Juan adds, "For now, they are given at the last line of treatment, when previous options have failed. If at some point they are approved for earlier use, the observed risk would likely be even lower, as patients would not have been subjected to prior chemotherapy cycles."

Melero points out that their use might be more questionable "if approved for other indications like autoimmune diseases, especially in children. Some of these diseases can be severe and disabling, but not fatal." However, "the risk is very low and probably also tolerable in these indications for non-malignant diseases."

Has anything changed then?

Both the FDA and EMA will continue to review emerging data, as they have done since the use of these therapies began. The current message is clear, and as the FDA states, the benefits for current uses outweigh the potential risks.

The investigation has led to two changes, which Manel Juan considers "of little importance":

- The FDA has decided to add information about the risk in the form of a boxed warning to highlight it in the drug's leaflet (this is the highest safety warning that can be assigned to a medication). In any case, as the EMA notes, the risk of developing secondary tumors was already specified in the product information since their approval.

- Both agencies have decided that patients treated with CAR-T therapies will be followed for life to study if a secondary tumor develops. Previously, the follow-up was required for 15 years, although, according to Manel Juan, who participates in developing academic or non-commercial CAR-T treatments, "they already required us to do that for our products."

For the immunologist, the agencies "have done what they had to do, which is analyze the data and inform about it." However, he feels that "unnecessary noise and alarm have been generated, probably due to the actions of some media outlets."

In an analysis article in the JAMA journal, oncologist Caron Jacobson at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston was somewhat more critical: "I have no issue with the FDA investigation or that the FDA made the investigation public. I do think, however, that the FDA did not do a good enough job of making it clear that the majority of these cases have not yet been linked directly to the CAR T-cell therapy, and patients with B-cell cancers are at risk of developing T-cell cancer as well. I also think it was premature to issue boxed warnings for all products for the same reason."

According to Peter Marks, director of the FDA's Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, such warnings "are not uncommon for cancer treatments." Responding to Jacobson, he said, "No one is arguing that the benefits greatly outweigh the risks, but anytime there is uncertainty—and we can’t put a measure on the uncertainty—we feel it is our duty to help inform physicians. I hope it does not change their thoughts about using these therapies in the right cases."