Reactions: World Meteorological Organisation declares onset of El Niño conditions

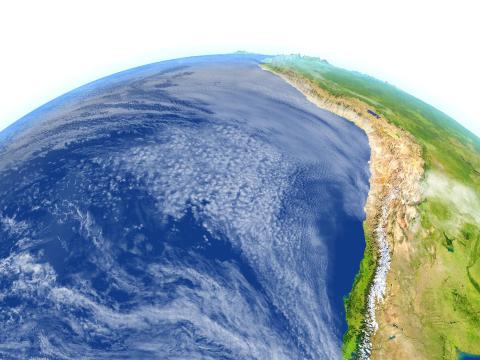

The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) has declared the onset of El Niño conditions on Tuesday. "The declaration of El Niño by the WMO is the signal for governments around the world to mobilise preparations to limit the impacts on our health, our ecosystems and our economies," said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas. According to the WMO statement, El Niño conditions have developed in the tropical Pacific for the first time in seven years, setting the stage for a likely rise in global temperatures and altered weather and climate patterns.

Javier Martín-Vide - El Niño EN

Javier Martín-Vide

Professor of Physical Geography

The confirmation by the World Meteorological Organisation that we are already experiencing an El Niño phenomenon and that it will most probably continue during the second half of the year alerts us to the fact that it will contribute, as has happened in the case of previous El Niños, a thermal plus or addition of a few tenths of a degree centigrade to the global average surface air temperature of the current 2023 or, due to the inertia of the climate system and the possible continuation of the phenomenon, of 2024. As is well known, a few tenths of a degree Celsius more in the global mean air temperature is by no means a negligible variation. In addition, this probable extra warming is coupled, in the same direction, with a strong positive thermal anomaly that has been present for weeks in the waters of the North Atlantic and North Pacific. It is therefore likely that one of the two years in question could be the warmest in instrumental history.

In addition, some weather extremes, such as heat waves and droughts in some regions and torrential rainfall in others, are expected to increase in frequency and intensity. For the record, the most intense El Niño of the 20th century, that of 1982-83, coincided with the torrential rainfall in the Júcar basin that led to the Tous reservoir in October 1982, and with the very heavy rainfall, with floods and landslides, in the Catalan Pyrenees in November of the same year.

Darío Redolat - El Niño EN

Darío Redolat

Climate change and meteorology consultant

El Niño is a phenomenon of natural variation of the Pacific Ocean thermocline layer that has important global implications. During its active phase it can increase the global average temperature by 0.4°C, with large areas of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean having anomalies of more than 2 and 3°C. El Niño is not responsible for global warming, but "gives back" some of the energy absorbed by the ocean during the neutral or La Niña phase, when negative anomalies occur.

Its implications translate into a decrease in the Asian monsoon, the rainy season in the Caribbean or changes in the patterns of marine ecosystems on the coasts of South America, among others.

In the specific case of Spain, no significant correlations have been observed between atmospheric temperature and sea surface temperature in the Pacific that last notably over time. It is true that weak correlations have been found between a positive El Niño phase and a warmer than normal late autumn (specifically for El Niño 1+2, the one closest to South America), but these are not lasting patterns. As for precipitation anomalies, the relationships are even more chaotic and vary greatly depending on location, so it is not appropriate to speak of a specific El Niño effect in Western Europe in general terms. In this case, the direct correlations are linked to oceanic and atmospheric patterns over Europe and the North Atlantic.

As has been observed after other El Niño events (1976, 1998, 2015) in a context of climate change, such excess heat is hardly compensated by La Niña and other subsequent global climate events, so that thermal anomalies persist and are abruptly aggregated with successive such episodes.

Ernesto Rodríguez - El Niño EN

Ernesto Rodríguez Camino

Senior State Meteorologist and president of Spanish Meteorological Association

El Niño is the positive phase of a quasi-periodic phenomenon - called El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) - mainly related to the warming of the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. Historically, it is known to recur with a frequency of between 2 and 7 years, starting to develop between April and June and reaching its maximum intensity between October and February. It typically lasts between 9 and 12 months, although it has occasionally lasted 2 years. The phenomenon is the cause of climatic anomalies in remote areas of the Earth - the so-called climate teleconnections - which make it possible to establish relationships between these anomalies - e.g. heavier precipitation, droughts, etc. - and the phase and intensity of the ENSO phenomenon.

The intensity of ENSO - measured as the warming (or cooling in negative phases) of specific areas of the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean - also determines the intensity of climate anomalies in remote areas. Years in which a strong El Niño event occurs favour an increase in the average surface temperature of the atmosphere, and if this is coupled with the global warming trend due to greenhouse gases emitted by the increasing use of fossil fuels, the annual average temperature of the atmosphere is quite likely to break records.

The WMO has declared the beginning of a positive ENSO phase and seasonal predictions from a variety of models indicate that this phase will continue for the time being over the next few months. Whether a record annual mean temperature will be broken will depend, among other factors, on the eventual intensity of the El Niño event that is now beginning. Intense events are associated with significant climate anomalies in certain areas of the globe, particularly in land areas around the equatorial Pacific Ocean, but they are hardly detected in Western Europe as other factors affecting climate variability are often more relevant over this part of the globe.

In short, we are likely to see an impact on global mean warming, although this warming is not likely to be reflected in an exceptional way over Spain in the coming months beyond the gradual warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

Anna Cabré - El Niño EN

Anna Cabré

Climate physicist, oceanographer and research consultant at the University of Pennsylvania

El Niño has already arrived and this, added to the climate crisis, means that the world will experience new temperature records and weather extremes, with impacts on health (e.g. malaria outbreaks or extreme heat especially dangerous for farmers and outdoor workers), ecosystems (such as corals), infrastructure (energy grids at their limits), food security (collapse of crops affecting especially small farmers), conflict (episodes of intense heat are closely related to different types of violence), among others.

The globalised world is not prepared to cope with these temperatures and it is the most vulnerable people who suffer the most. We must cooperate to ensure immediate responses to the crises that arise, but also understand that drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions are urgently needed and that long-term, sustainable adaptation must be prepared that takes into account globalised and transboundary risks.