Reactions to the results of the phase 3 malaria vaccine R21 trial

In a clinical trial of nearly 5,000 children aged 5-36 months, a new malaria vaccine - called R21/MatrixM - reduced symptomatic cases by 68-75% over the following year. According to the authors, the vaccine will be inexpensive and could contribute to a substantial reduction in malaria suffering and deaths in sub-Saharan Africa. The results of the phase 3 trial are published in The Lancet.

Jaime J - Malaria (EN)

Jaime Jesús Pérez Martín

Specialist in Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Deputy Director General of Public Health of the Region of Murcia and President of the Spanish Association of Vaccinology

It is an excellent study, a clinical trial conducted in four African countries with a sample size of almost 5,500 children.

On the one hand, this vaccine had published results from phase 2 clinical trials and the results were concordant. Moreover, as the authors state, the vaccine is already licensed by the WHO and use has started in several African countries. The data are also concordant with those of another malaria vaccine already in use, namely Mosquirix, which was the first malaria vaccine licensed, so with this new vaccine we now have two. The most important new feature is that the efficacy data are higher than those obtained with Mosquirix, which has figures of 45-55% protection. Here we have increased to between 70 and 80%, that is to say, it offers a notable improvement in terms of protection.

Therefore, as a novelty, it provides greater protection and, at the same time, it will allow more extensive vaccination programmes against malaria than we have had up to now, because we will have a second vaccine with a large number of doses ready for use. Also as an added benefit we could have an increased duration of protection.

In addition, the vaccine uses a new adjuvant, Matrix-M, which so far has not been in use but may be a very promising adjuvant for use in many vaccines. In our country this adjuvant has only been used in Novavax covid vaccines, but unfortunately we have had few available, so our experience with this preparation is limited. Hopefully the benefits of this adjuvant can be confirmed in other vaccines.

As for limitations, there are those given by the authors themselves, such as not measuring efficacy against mortality, but that is very difficult in a clinical trial because logically these are ideal situations in which treatment should be given early. However, by measuring efficacy against the disease in real life we will achieve significant reductions in mortality, so I don't think this is a major limitation.

Consuelo - Malaria RS

Consuelo Giménez Pardo

Professor of Parasitology at the University of Alcalá (UAH) and director of the Master's Degree in Humanitarian Health Action (UAH-Doctors of the World)

The history of the search for malaria vaccines is a long road, full of successes and failures, but a necessary one in the fight against malaria in its most severe form. In fact, the international community has been working for decades to eliminate this parasitic disease, and this has led to important changes in the public health strategies adopted by the countries that suffer from it. Vaccination is one of the key strategies for the control of infectious diseases and the availability of safe vaccines that provide long-lasting protection against malaria is an important step forward in the fight against malaria. However, it must be considered in the context of the implementation of other effective interventions, such as the use of insecticide-treated bed nets and access to diagnostic and artemisinin-based combination therapies.

Factors such as disease burden, cost-effectiveness of the intervention, and coverage of other malaria control and elimination interventions must be considered when implementing vaccination. Vaccination should therefore be an additional intervention to be integrated into malaria control and elimination strategies, depending on the context of each setting and health system.

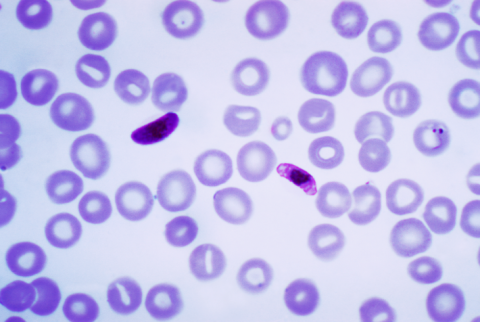

The vaccines with the highest proven efficacy act in the pre-erythrocytic phase through the inoculation of attenuated sporozoites, which have a higher proven efficacy, but are difficult to apply in endemic areas due to their storage and administration conditions (intravenous and with frequent doses).

There are also subunit vaccines. RTS,S/AS01E is available on the market, with limited proven efficacy but easier to administer and store, and the WHO has recently recommended the R21 vaccine for the prevention of malaria in children.

In this regard, the results of the study of a vaccine that is more immunogenic than RTS,S, which also acts on the circumsporozoite protein (CSP), were published in 2016. It is developed from hepatitis B virus surface antigens, leading to a higher proportion of CSP in the vaccine composition. The vaccine has already demonstrated immunogenicity in mice at very low doses.

The current study by Datoo et al (2024) continues work already published in Lancet published in 2021 and 2022. In this case, the phase 3 trial shows 75% efficacy against clinical malaria in seasonal malaria settings and 67% efficacy in routine malaria settings in children aged 5-36 months, and while there appears to be a decrease in efficacy over 3-month periods, for the first 12 months efficacy remains above 60%. In the double-blind trial conducted over one year in different areas of Burkina Faso, it uses a control group given rabies vaccine, which other studies have shown to be protective against meningitis. In this case, despite the limitations of the study, the authors propose that R21/Matrix-M is capable of being produced in terms of 100-200 million doses per year at a cost of less than $4 per dose and can help prevent malaria.

The truth is that the demand for malaria vaccines has never been greater, yet stocks of the already marketed vaccine, RTS,S, are limited. Now, with R21/Matrix-M on the WHO recommended list of malaria vaccines, it is hoped that the supply will be sufficient to immunise all children living in areas where malaria is a public health risk. As such, it is proposed to be cost-effective and safe, so that the choice of vaccine will be made in each country according to the characteristics of the programmes, vaccine supply and affordability. As with other new vaccines, the potential toxicity of the vaccine will continue to be monitored.

The main challenge facing the malaria vaccine is the integration of vaccination into the health system as an intervention in the malaria control and elimination strategy. Thus, it should be able to be integrated into the vaccination schedule that is already in place.

But when it comes to malaria vaccines, there are no panaceas. It has to be taken into account that for subunit vaccines the proven efficacy is low and limited to the 5-7 months age range, for adults the figures decrease to 34% efficacy and, according to the available evidence, protection does not seem to be prolonged over time, so that vaccinated children would again be exposed to malaria at a very young age.

Overall, efforts should be directed towards improving capacities, both in terms of human resources and infrastructure, to efficiently monitor and manage insecticide resistance, as well as to make available appropriate and affordable new products (insecticides, treatments and vaccines) useful for malaria control.

Dobaño - Malaria (EN)

Carlota Dobaño

Research professor and Head of the Malaria Immunology Group at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal)

Phase 3 clinical trials for vaccine registration, such as this one, are rigorously executed studies under external monitoring, and the design and performance is under scrutiny by WHO expert committees before recommending this R21 vaccine and by external reviewers from the Lancet. Thus, the study is generally of good quality, although with certain limitations that are mentioned in the discussion and discussed below.

The study demonstrates the utility of a second malaria vaccine developed in Oxford, with a formulation very similar to the first vaccine that the WHO recommended after another larger multicentre phase 3 trial and a series of pilot implementation studies in three African countries (RTS,S/AS01E or GSK's Mosquirix). Both consist of a malaria parasite antigen based on the circumsporozoite protein from the surface of Plasmodium falciparum injected by the transmitting mosquito, fused to the hepatitis B virus surface antigen and formulated with an adjuvant that stimulates an inflammatory response by the innate immune system, and induces high levels of antibodies to the parasite.

The vaccine shows high efficacy in areas of seasonal malaria when administered just before the rainy months associated with high transmission of infection, and less efficacy in sites of less intense and perennial transmission. The authors suggest that a large number of vaccine doses can be produced cost-effectively, which will benefit more African children, given the current manufacturing limitations of the other available vaccine. As with the covid-19 pandemic, the availability of more than one vaccine allows for greater coverage. Both vaccines are considered first-generation vaccines, with improving efficacy, and further research is needed to investigate knowledge gaps (e.g. why they do not protect 90-100% of children) in order to optimise them for second generations.

The duration of efficacy of such a vaccine still needs to be monitored to further assess its public health impact, as well as its efficacy in areas of Africa where malaria transmission is high and year-round. The two East African sites included have very low malaria transmission at present and are not fully representative of the epidemiology that exists in much of the continent's endemic areas, where malaria is one of the leading causes of illness and mortality in the population.

Datoo et al.

- Research article

- Peer reviewed

- Randomized

- Clinical trial

- People